In previous decades, the therapies for congestive heart failure (CHF) were limited both with respect to options and their ability to modify the underlying disease process. Recent advances in mechanical assist devices and cardiac transplantation have increased the outlook and longevity of patients suffering from CHF. Over 9,000 continuous flow left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) were implanted between 2006 and 2013.1 An unavoidable result of these advances is an increasing incidence of their complications. This review will address the initial approach and management to a patient who presents with a cardiac mechanical assist device in the emergency department.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 36 – No 08 – August 2017

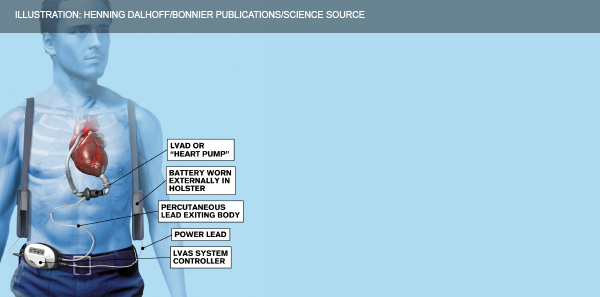

(click for larger image) Figure 1: Continuous-flow left ventricular assist device.

Source: N Engl J Med. 2009;361(23):2241-2251.

Patients with refractory advanced heart failure who have failed medical therapy qualify for consideration of a LVAD as a bridging therapy while they undergo evaluation for cardiac transplant. The LVAD acts as a pump that receives blood from an internal cannula in the left ventricle (LV) and ejects the blood via an outflow cannula through the ascending aorta (see Figure 1).2

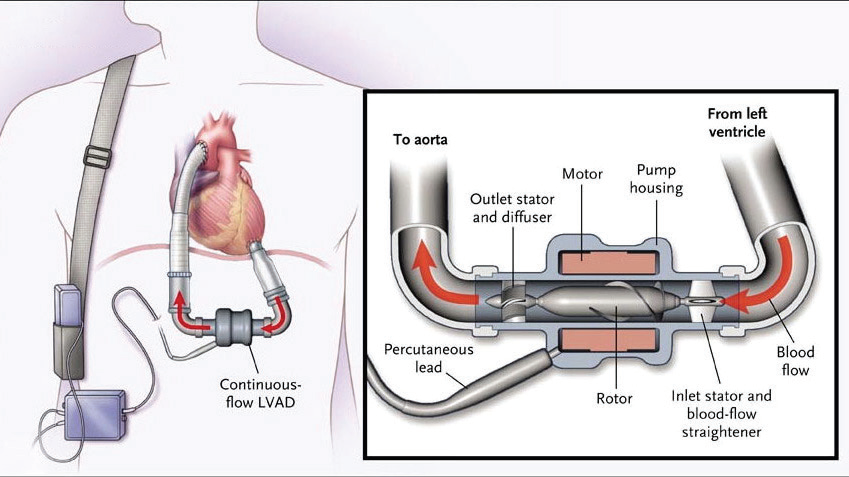

Figure 2: Components of a left ventricular assist device.

ILLUSTRATION: Henning Dalhoff/Bonnier Publications/Science Source

The LVAD (see Figure 2) poorly mimics the native cardiac cycle as it pumps continuously through systole and diastole with limited variation in flow.2 The net effect is an obliteration of pulse pressure and the ability to palpate a pulse, which makes initial assessment in the emergency department challenging. The most frequent complications physicians will encounter include infection, thrombosis, hypotension, bleeding, dysrhythmias, and device failure.

Initial Assessment

LVAD patients should immediately be assessed for signs of poor perfusion and volume resuscitated as appropriate. Auscultate for a precordial/epigastric “hum”—absence of this indicates pump failure.2 LVAD patients are supported and followed longitudinally by a multidisciplinary team. Early involvement of a patient’s LVAD coordinator should be considered once a patient has been stabilized.

Next, obtain a blood pressure. You will need to calculate their mean arterial pressure (MAP) by attaching a manual blood pressure cuff and inflating it to >120 mmHg. Then, slowly deflate the cuff while listening for a brachial pulse using a Doppler.2 The pressure reading at which arterial flow becomes audible is their MAP (normal: 60–90 mm Hg). Afterwards, double-check that the external controller device connections are secure and take note of the pump speed (rpm), flow (L/min), power (watts), and battery life on the external controller (see Table 1).3 Finally, get an ECG in all of these patients. Now let’s troubleshoot!

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

5 Responses to “How to Manage Emergency Department Patients with Left Ventricular Assist Devices”

August 23, 2017

Z BasThis is a great review. Thank you so much. I feel like I now have an approach to LVAD patients, should they ever come into my ED.

August 27, 2017

RobErrata: Under Bleeding, should read “arteriovenous malformations” in the GI tract.

Great article!

August 28, 2017

Dawn Antoline-WangThank you, we’ve made the correction.

August 31, 2017

CRThanks for a great concise review!

October 14, 2017

Kevin WebbThank you for the great review. I will forward this to our Paramedics.