Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 33 – No 08 – August 2014CDC partners with ACEP to disseminate info about disseminated Lyme: critical update on Lyme carditis

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Case-patient details have been changed to protect confidentiality.

The Case

On a late-summer afternoon, an otherwise healthy 32-year-old woman presented to an urgent care facility in New York complaining of episodic shortness of breath for the past week. She became quite anxious when these episodes occurred but couldn’t identify any precipitating activities or events. The patient reported vacationing in the Northeast during the previous two weeks and had frequented woody areas where she was exposed to ticks. She denied fever, rash, muscle pain, or joint pain. Providers in the urgent care facility diagnosed the patient with anxiety and prescribed clonazepam. No electrocardiogram (ECG) was performed.

The following day, the patient collapsed and died. Serum obtained at autopsy revealed a strong serologic response to infection with Borrelia burgdorferi spirochetes, the causative agent of Lyme disease. Examination of decedent heart tissue revealed characteristic histopathologic findings of Lyme carditis (see Figure 1). B. burgdorferi sensu stricto spirochetes were seen after Warthin-Starry stain of heart tissue (see Figure 2) and confirmed by immunohistochemistry and polymerase chain reaction.

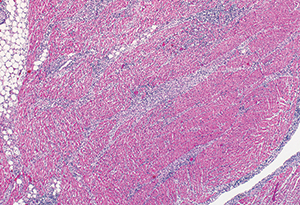

Figure 1.

Above: Hematoxylin and eosin stain at 6.25x magnification of decedent heart tissue demonstrating characteristic interstitial perivascular lymphoplasmacytic pancarditis.

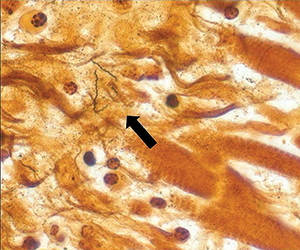

Figure 2.

BELOW: Warthin-Starry stain of decedent heart tissue at 158x magnification demonstrating Borrelia burgdorferi spirochetes (arrow).

Discussion

On Dec. 13, 2013, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published a report describing three cases of sudden cardiac death associated with Lyme carditis in otherwise healthy young adults ages 26 to 38.1 While two of the case-patients described in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report did not seek care before their deaths, one did but was not diagnosed with or treated for Lyme disease.

Lyme disease is a zoonotic, multisystem illness caused by the spirochete B. burgdorferi, which is transmitted by certain Ixodes spp ticks. Approximately 30,000 cases are reported to the CDC each year, primarily from high-incidence states located in the northeast (Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont) and north central (Minnesota and Wisconsin) United States.2 The actual number of annual infections is estimated to be tenfold higher; Lyme disease is the most common vectorborne disease in the United States.3

Acute clinical illness is usually characterized by fever and constitutional symptoms combined with a distinctive rash, erythema migrans (EM), which develops at the site of the tick bite in approximately 70 to 80 percent of patients.4 However, without early appropriate antibiotic therapy, infection can disseminate to other tissues, causing peripheral and central neuropathy, arthritis, and carditis.

Lyme carditis, which most commonly manifests as atrioventricular (AV) conduction block, results from the host inflammatory response directed at spirochetes in cardiac tissue. Among Lyme disease case-patients reported to the CDC, approximately 1 percent had documented Lyme carditis (defined as associated second- or third-degree AV block). Although death is extremely rare, second- and third-degree AV block can progress to fatal arrhythmias if not managed and treated appropriately, underscoring the need for accurate and timely diagnosis.

Certain demographic groups appear to be at higher risk of developing Lyme carditis. Males and young adults are disproportionately affected by Lyme carditis [CDC; unpublished data]. Common symptoms of Lyme carditis include lightheadedness, palpitations, shortness of breath, chest pain, and syncope and can occur several days to six months after onset of disease (median of 21 days).5 Patients with Lyme carditis typically present during the summer months. Notably, a history of an EM lesion is reported less frequently in patients with Lyme carditis for unknown reasons [CDC; unpublished data]. However, absence of an EM lesion should not rule out Lyme carditis in an otherwise appropriate clinical scenario, although recommended serologic evidence of Lyme disease should be obtained to ensure correct diagnosis.

Emergency health care providers should consider Lyme disease in patients with cardiac symptoms who are residents of, or have recently traveled to, regions with high incidence of Lyme disease. Additionally, emergency health care providers should investigate heart block in patients with Lyme disease if clinically indicated. Importantly, providers are advised to consider obtaining an ECG in men and young adults from, or with recent travel to, high-incidence Lyme disease areas who present with symptoms of Lyme carditis, such as chest pain, palpitations, lightheadedness, shortness of breath, and syncope, particularly during summer and fall months.

Emergency physicians are in a unique position to recognize and diagnose Lyme disease before it progresses.

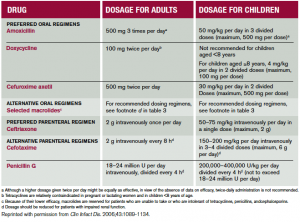

Recommended treatment algorithms for Lyme carditis have been established by the Infectious Diseases Society of America, and readers are directed there for additional therapeutic information (see Table 1).6 Hospitalization and continuous cardiac monitoring should be considered for symptomatic patients, any patients with second- or third-degree heart block, or those with first-degree block with a prolonged PR interval (>30 milliseconds).6 Confirmatory laboratory evidence of infection should not delay supportive care in appropriate clinical scenarios. Recommended parenteral antibiotics should be administered during hospitalization.6 For patients with severe heart block, a supportive temporary pacemaker may be required. The prognosis is generally excellent with appropriate antibiotic therapy. Most patients will experience resolution of symptoms and ECG abnormalities within one to six weeks, depending on the degree of initial conduction disturbance.7,8 An oral antibiotic regimen can be used to complete a course of therapy upon hospital discharge.6

Table 1. Recommended Antimicrobial Regimens for Treatment of Patients With Lyme Disease.The management options considered included oral antimicrobial therapy for patients with a single erythema migrans skin lesion and oral versus parenteral therapy for patients with clinical evidence of early disseminated infection (ie, patients presenting with multiple erythema migrans lesions, carditis, cranial nerve palsy, meningitis, or acute radiculopathy).

While Lyme carditis is an uncommon manifestation of Lyme disease, it is also one of the most serious. Emergency health care providers are in a unique position to recognize and diagnose this potentially life-threatening illness before it progresses. Additional information about the prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and epidemiology of Lyme disease can be found at www.cdc.gov/lyme.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the coauthors of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report describing this investigation:1 Gregory Ray, MD, Thadeus Schulz, MD, Wayne Daniels, DO, Cryolife, Inc., Kennesaw, Georgia; Elizabeth R. Daly, MPH, New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services; Thomas A. Andrew, MD, New Hampshire Office of the Chief Medical Examiner; Catherine M. Brown, DVM, Massachusetts Department of Public Health; Peter Cummings, MD, Massachusetts Office of the Chief Medical Examiner; Randall Nelson, DVM, Matthew L. Cartter, MD, Connecticut Department of Public Health; P. Bryon Backenson, MS, Jennifer L. White, MPH, Philip M. Kurpiel, MPH, Russell Rockwell, PhD, New York State Department of Health; Andrew S. Rotans, MPH, Christen Hertzog, Linda S. Squires, Dutchess County Department of Health, New York; Jeanne V. Linden, MD, Wadsworth Center, New York State Department of Health; Margaret Prial, MD, Orange County Office of the Medical Examiner, New York; Jennifer House, DVM, Pam Pontones, MA, Indiana State Department of Health; Brigid Batten, MPH, Dianna Blau, DVM, PhD, Marlene DeLeon-Carnes, Atis Muehlenbachs, MD, PhD, Jana Ritter, DVM, Jeanine Sanders, Sherif R. Zaki, MD, PhD, Division of High-Consequence Pathogens and Pathology, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Disease; Paul Mead, MD, Alison Hinckley, PhD, Christina Nelson, MD, Anna Perea, MSc, Martin Schriefer, PhD, Claudia Molins, PhD, Division of Vector-Borne Diseases, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Disease.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Three sudden cardiac deaths associated with Lyme carditis–United States, 2012–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:993-996.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Notice to readers: Final 2012 reports of nationally notifiable infectious diseases. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(33):669-682.

- Hinckley AF, Connally NP, Meek JI, et al. Lyme disease testing by large commercial laboratories in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2014 May 30;pii:ciu397. [Epub ahead of print]

- Correspondence. The presenting manifestations of Lyme disease and the outcomes of treatment. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2472-2474.

- Fish AE, Pride YB, Pinto DS. Lyme carditis. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 2008;22:275-288.

- Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1089-1134.

- McAlister HF, Klementowicz PT, Andrews C, et al. Lyme carditis: An important cause of reversible heart block. Ann Intern Med. 1989;1110:339-345.

- Forrester JD, Mead P. Third-degree heart block associated with Lyme carditis: Review of published cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2014 May 30;pii:ciu411. [Epub ahead of print]

Dr. Forrester is an epidemic intelligence service officer with the CDC Division of Vector-Borne Diseases in Fort Collins, Colorado. His work involves epidemiologic investigations related to Lyme disease, plague, tickborne relapsing fever, tularemia, and other infectious diseases. He is a categorical general surgery resident at Stanford University.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Risk of Sudden Cardiac Arrest from Lyme Carditis Underscores Need for Timely Diagnosis, Treatment”