Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 42 – No 08 – August 2023Current Professional Positions: Assistant professor of emergency medicine, director of health policy: advocacy, assistant director of faculty development, department of emergency medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston

Internships and Residency: Emergency medicine residency, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

Medical Degree: MD, Cornell Medical College (2007)

Response

No patient should be seen in an emergency department (ED) without the involvement of a residency-trained, board-certified (or board-eligible) emergency physician (EP). ACEP defines this as the gold standard in emergency care. However, we cannot forget that rural areas face significant shortages of emergency physicians. Despite the growth we have seen in residency programs, we are not seeing more emergency physicians working in remote EDs. Recent data published in Annals showed that between 2013 and 2019, the percentage of clinicians working in rural areas who were emergency physicians actually dropped slightly.

It is critical for our specialty to work on our rural pipeline. This means supporting efforts to recruit college students from rural areas in their pre-med years and support their transition into medical school, then continuing to expose medical students to the experience of rural medicine during their clerkship years. If we wait until residency for trainees from urban areas with only urban experiences to get firsthand experience in a rural setting, it may be too late to persuade them of the value of a rural career. This limitation does not mean that rural rotations should not be supported. Rural rotations for emergency medicine residents need to be prioritized and made much more accessible. Trainees should be incentivized to participate in these rotations with optimized scheduling, supported housing, and an additional stipend to cover the expense of being away from home. We must work to reduce structural and accreditation barriers to the availability of these rotations through enhanced collaboration with the ACGME, CORD and program directors, rural EPs and rural hospitals. Practicing in a rural area can be deeply rewarding with opportunities to spend more time at the bedside and develop deeper relationships with a smaller cadre of ED staff. The more positive experiences we can create for trainees within rural practices, the more EPs we can attract to these areas.

As the problem of strengthening the rural pipeline cannot be solved overnight, in the interim, we will continue to see some nurse practitioners and physician assistants developing careers in rural emergency departments. Evidence shows that their presence has been increasing in rural EDs, and ACEP’s own Rural Task Force identified in 2020 that some rural EDs may not have sufficient volume to support dedicated ED physician staffing. However, both the Rural Task Force (2020) and the Telehealth Task Force (2021) agreed that telehealth supervision of NPs and PAs in rural practice environments by board-certified emergency physicians is a viable model for improving patient safety and extending the reach of the BC EP through the use of a physician-led team. A “hub and spoke” model allows a centrally located board-certified EP to collaboratively supervise NPs and PAs in multiple hospitals simultaneously. Continuous improvements in technology and broadband capability mean that this kind of supervision will become easier every year and can allow true team-based care even without an emergency physician physically present at the bedside. To optimize this kind of care, we must ensure that our trainees are learning the skills they will need to be effective in this role, including strategies for effectively supervising NPs and PAs and how to effectively use telehealth technologies to evaluate patients, from building rapport to performing video physical exams.

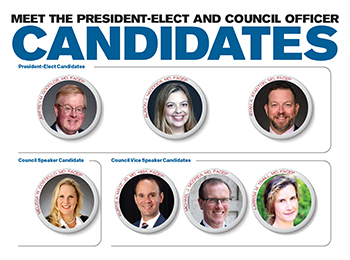

No Responses to “2023 ACEP Elections Preview: Meet the President-Elect and Council Officer Candidates”