Explore This Issue

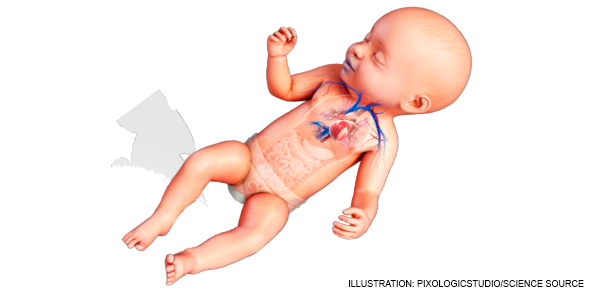

ACEP Now: Vol 37 – No 05 – May 2018The traditional approach to congenital heart disease (CHD) involves a detailed understanding of the pathophysiology, clinical findings, and management of each particular congenital heart defect. However, this cognitive-heavy approach is not practical for the emergency physician faced with an undifferentiated, unstable infant when decision making must be rapid. Despite improved CHD screening in recent years, a small but significant minority of these patients will be undiagnosed when they present to the emergency department.

In this EM Cases column, a simple approach is outlined, allowing the emergency physician to focus on time-sensitive, lifesaving treatments and practical management of the acutely ill infant with CHD.

The Three-Step Approach1

- Age: Younger than or older than 1 month? Any infant younger than 1 month old with central cyanosis or shock should be considered to have critical duct-dependent CHD until proven otherwise. This is almost always a left heart lesion such as tetralogy of Fallot, which almost always benefits from prostaglandins. Shunting or mixing lesions such as ventricular septal defect (VSD) or patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) typically present later during infancy, usually after 1 to 6 months of age.

- Color: Do they appear pink, gray, or blue? Infants with undiagnosed CHD usually present to the emergency department in one of three ways:

- Pink: Pink-appearing infants with CHD who present to the emergency department with dyspnea should have underlying acute congestive heart failure (CHF) near the top of the differential diagnosis. They have adequate pulmonary blood flow and are relatively well perfused and oxygenated. Heart failure in these patients usually occurs due to a shunting lesion. Always consider CHF in a wheezing pink child. The most sensitive and specific clinical findings for acute CHF in infants include: 1) less than 3 ounces of formula per feed (or greater than 40 minutes per breast feed); 2) a respiratory rate greater than 60 breaths per minute (or irregular breathing); and 3) hepatomegaly.2 Other clues include poor weight gain and ventricular hypertrophy on ECG.

- Gray: Gray-appearing infants with CHD are usually in shock with circulatory collapse due to poor systemic flow and oxygenation due to a left-side obstructive, duct-dependent lesion. These patients will almost always benefit from fluid administration and, if younger than 1 month in age, prostaglandins.

- Blue: The blue appearance of central cyanosis (ie, blue discoloration of the tongue, mucous membranes, and lips) in the setting of CHD usually occurs due to a right-side obstructive duct-dependent lesion in the first month of life or a mixing lesion after one month of life. These infants, like the gray ones, almost always require prostaglandins. There are four important etiologies to always consider in infants with central cyanosis: 1) CHD; 2) sepsis; 3) respiratory disorders (such as pneumonia); and 4) hemoglobinopathies (such as polycythemia and methemoglobinemia).

- Physical Examination and Bedside Tests Observing the following can provide important clues to the underlying diagnosis: the infant’s work of breathing, limb-pulse differentials, blood pressure and pulse oximetry, hyperoxia test results (see below), ECG for left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) or right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH), and bedside cardiac ultrasound for global cardiac function, septal defects, and chamber count. After determining the infant’s color, the most important clue to CHD observed from the foot of the bed on physical exam is silent tachypnea. Tachypnea with increased work of breathing is usually due to a respiratory cause. In contrast, tachypnea without increased work of breathing—ie, silent tachypnea—is usually secondary to metabolic acidosis from a cardiac or metabolic cause.

In addition to silent tachypnea, the hyperoxia test helps differentiate respiratory causes from cardiac causes of tachypnea.3 This test was originally described using the PaO2 garnered from the arterial blood gas. Although accurate, this is a cumbersome, painful, and lengthy process.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Single Page

4 Responses to “A 3-Step Approach for Infants with Congenital Heart Disease”

June 7, 2018

Hexham khaledExcellent

February 25, 2019

Iman Ali Ba-SaddikA simplified approach which serves as a very good practical guide to congenital heart disease

July 5, 2019

Sunita Harkar ShallaWell written and very informative.

July 22, 2020

AmeenVery informative, Thank you so much.