One option is to avoid the use of physical restraints and instead hold the patient down by security for the few minutes it takes for the calming medications to take effect. The other option is to place the physical restraints on the patient, immediately administer intramuscular (IM) calming medications, and release the restraints as soon as the patient is calm. Physical restraints should always be followed by immediate sedation.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 37 – No 11 – November 2018When used properly, physical restraints can be quite safe.5 However, improper use can be lethal. In one study, 26 deaths were presumed to be the direct result of improper physical restraints.6 Avoid covering the agitated patient’s mouth and/or nose with a gloved hand. This can lead to asphyxia, metabolic acidosis, and death. Use an oxygen mask to prevent the patient from spitting on staff. This may also serve to improve oxygenation. With the patient in the supine position with about 30 degrees head elevation, use four-point restraints tied to the bed frame (rather than the rails), with one arm above the head and the other below the waist.

Step 4: Chemical Restraint or Sedation

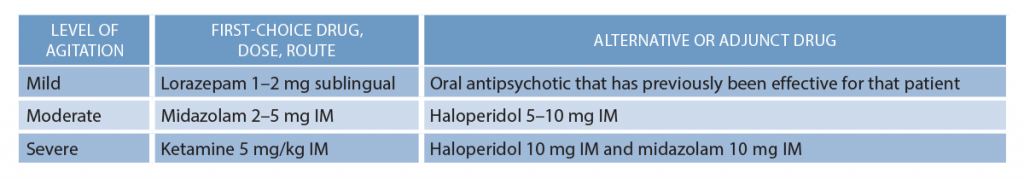

The goal of calming medications is to enable rapid stabilization of the acutely agitated patient and to enable the expeditious search for potential life-threatening diagnoses. The choice of route depends on how agitated your patient is. For cooperative mildly agitated patients, offer oral or sublingual medications first. For uncooperative moderately and severely agitated patients, the safest option is to start with IM medications.

Calming medication options include ketamine, benzodiazepines, and antipsychotics.

Whenever possible, tailor the therapy to the underlying diagnosis (eg, psychotic psychiatric disorder, alcohol withdrawal, drug intoxication, etc.). While the evidence for one regimen over another is lacking, current evidence-based recommendations are summarized in Table 1.

IM midazolam is the best benzodiazepine option in moderately to severely agitated patients as it is quickly and reliably absorbed. In alcohol-intoxicated patients, beware of respiratory depression with benzodiazepines and place them on a cardiac monitor, ideally with end-tidal CO2 monitoring for early detection of respiratory depression.

Haloperidol should be considered an adjunct to benzodiazepines for moderate and severe agitation and may be appropriate as monotherapy in moderately agitated intoxicated patients who cannot be placed on a monitor when resources are limited.7–9 Be aware that haloperidol has a longer half-life than midazolam, which can result in the patient staying in your emergency department for much longer than would be necessary otherwise. Although haloperidol prolongs the QTc, this effect is very unlikely to be clinically consequential at the doses typically used for emergency agitation. Nonetheless, caution is advised in patients who are already taking multiple QTc-prolonging agents. Consider obtaining a baseline ECG first in these higher-risk patients.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Single Page

One Response to “A 5-Step Approach to the Agitated Patient”

November 25, 2018

TIM Quigley D PETERSONThanks Anton.

One comment on ketamine after thirty years experience with it. 5mg/kg is a huge dose. 2mg/kg or 3mg/kg almost always works with my EMS providers. The time frame for ED doc to reassess is also shortened. I suggest a dose range like 3-5mg/kg.

It’s funny that the ED docs complain when EMS “oversedates,” but remain silent when THEY order the medication and the patient is drowsy longer.

tqp