A difficult airway is every emergency physician’s worst nightmare. The decision to intubate a patient needs to be coupled with adequate preparation, good communication with nurses and other team members, and a backup plan for possible complications. These situations require rapid decision making under stress. The case below depicts a real-life situation that resulted in a medical malpractice lawsuit. The descriptions and figures shown are the actual evidence used in the lawsuit.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 39 – No 09 – September 2020The Case

A 52-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath. She was brought to the emergency department in a wheelchair by her husband. The triage nurse immediately recognized that she was in severe respiratory distress. Her respirations were noted to be rapid and labored, and she had an audible gurgle. She was assigned a triage Level 1.

There were no available rooms, so she was put in a hallway bed. The physician was immediately at the bedside. He noted that she was cool, clammy, and grossly cyanotic. The patient was able to state that she did not have asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease but did note a history of congestive heart failure. After a very limited history, the patient’s respiratory status declined into complete apnea. The physician made an initial attempt at blind nasal intubation while the nurses started an IV, but he was unsuccessful. A second attempt was made, also with no success. By that time, the nurses had cleared a room and she was brought into the resuscitation bay. The patient’s heart rate declined to 40 bpm on the monitor, a pulse could not be palpated, and chest compressions were started. One milligram of epinephrine was given.

By then, the nurses had established an IV, and 5 mg midazolam (Versed) was given. An oral intubation was attempted without any success. The doctor then elected to place a King Airway device. The patient was ventilated through the King Airway, return of spontaneous circulation was obtained, and her oxygen saturation increased to 97 percent.

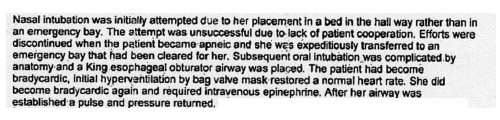

A portion of the doctor’s note describing the events is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Over the next 10 minutes, the patient’s oxygen saturation declined to the mid-80s. She was given lorazepam (Ativan) for sedation and furosemide (Lasix), as the physician suspected fluid overload. The physician also prescribed dexamethasone (Decadron) and diphenhydramine (Benadryl) to reduce airway swelling as well as metoprolol due to the fact that she was hypertensive. Outside medical records were obtained showing that she had a coronary artery bypass graft approximately 18 months earlier.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Single Page

No Responses to “A Patient Transfer Leads to a Lawsuit”