Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 40 – No 06 – June 2021Dr. Erik Anderson holds a patient’s hand during a procedure.

BT: What’s been the impact of COVID-19 on the community and patient population at your hospital system?

EA: If we were to step back from the very beginning, at my health care system and across Northern California, we were seeing a lot of essential workers, particularly in the Latin(x) community, who were disproportionately impacted by COVID-19. Figuring out how to tailor interventions and education for that community was something that was going on early and still persists today. There is a significant indigenous Mayan community in Alameda County that has been tremendously affected by COVID, and there was essentially no COVID health information in the spring and summer of 2020 in any Mayan languages. There are these pockets of disparity among our patient populations that we do our best to navigate through.

I do addiction medicine as well, and there has been a lot written about increasing overdose deaths during the pandemic. We were really worried early on when our patients stopped showing up to the emergency department and clinic. The fear was that people were using more drugs and using them alone in a period of isolation. You never want that. A lot of my work has been focused on addressing this and keeping people safe.

BT: How has COVID affected the way you approach patients?

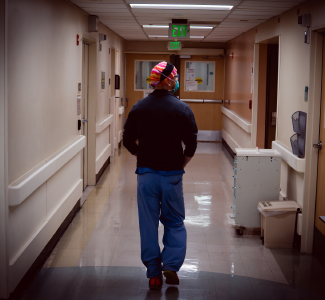

Dr. Erik Anderson walks down a hospital hallway.

EA: My spouse and I worked on the Navajo Nation before we moved back to California. One thing that was really important there was, when you walked into a room, you’d shake the hand of the patient. You’d also shake everybody’s hand who was in the room with the patient, often family members. It was an important thing that you greeted everybody by shaking their hand. Coming back to California, that was something that I continued to do. Now, there is this unseen barrier of germs and viruses and the physical barriers of masks and gloves that change a lot about the patient encounter. Pre-vaccine, there was this fear that anyone could have COVID-19, so I always need to have my guard up. Maybe that means you are standing farther away from the patient when normally you would be close to their bedside. I think that changes the dynamic of what patient and providers see and feel in a negative way.

BT: How has the pandemic affected your personal life?

EA: It’s been hard, like it has been for everybody else. My wife is a primary care physician in addiction medicine as well. That transition between pre-COVID and COVID seemed like it happened very fast. We were working the whole time, and that stress of keeping your family safe and finding ways to do that with childcare was difficult. Trying not to be sick was just something that we never thought about. Getting sick with a virus was just not that big a deal before. Just recently, we agreed that we should write a will. Having to go through that was so emotionally difficult with small kids at home. But things are getting better. As much of the night and day from pre-COVID to COVID, it’s getting pretty darn close in terms of the post-COVID vaccine era. While still stressful to be at work and wear an N95 all the time, the emotional burden of going to work is so much less after the vaccine. I can’t believe we did that for a whole year. Coming home, taking your clothes off outside, and taking a shower immediately, hoping you didn’t bring something home, was a totally bizarre and difficult thing for our profession.

BT: Where do you see us a year from now?

EA: A year from now, I think COVID will still be out there globally. I think we will be getting ready for our booster shots. There will be more ability to see people and socialize, but we will still be living with COVID in a manageable way.

BT: How do you see emergency medicine changing when COVID is over?

EA: It’s hard to imagine not wearing masks at work, at least for patient encounters. It’s almost hard to remember intubating somebody without a mask on, let alone without an N95. I can’t imagine intubating someone without eye protection and an N95 for a very long time. We weren’t doing that regularly before COVID.

I’m interested in the public health interface of emergency medicine, and I think now we are going to be more aware of our role in population health. Before COVID, I was working a lot on HIV and hep-C screening in the emergency department, and that I think will become more easily understandable as a role of emergency medicine. On top of resuscitating patients, we have a part in public health and improving disparities in our communities. That’s what our specialty is.

BT: Any final thoughts?

EA: Even though our world has gotten smaller with COVID in terms of social distancing, it has been nice to feel closer with smaller groups of people. Our relationships with some people have grown this past year, given this shared experience. I hope that continues.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

No Responses to “A Year of Coping with COVID—Q&A with Dr. Erik Anderson”