Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 36 – No 03 – March 2017(click for larger image)

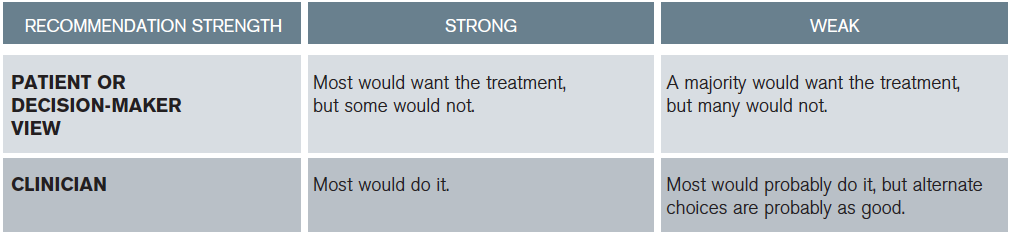

Table 2: Determining Strength of Recommendations1,2

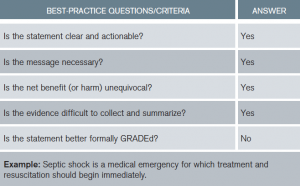

New to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology is the replacement of numbers and letters with “strong or weak” recommendations followed by quality of evidence (see Tables 2 and 3). Best-practice statements (BPSs) are recommendations to which the committee felt GRADE criteria could not be applied but pass the “common sense” test (see Table 4).

ED-Specific Recommendations and Changes

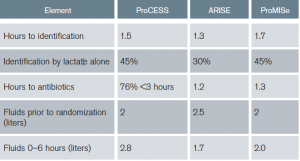

Early goal-directed therapy (EGDT) is no longer recommended. Specifically, given no benefit in the general population of septic patients, central venous pressure (CVP), hematocrit, and central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2) goals are not encouraged. Additionally, given no demonstrated harm, combined with no evaluation of specific subgroups, there is no recommendation against using some of the goals if the clinician feels indications exist. The original EGDT trial was pivotal in changing the mindset of clinicians around the world regarding sepsis time sensitivity and highlighting emergency physicians as the resuscitation experts.6 However, application over a decade later through three international randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and subsequent meta-analyses resulted in no difference between strict EGDT and usual care, with this important caveat.7–9 All three trials had protocols providing early identification (1–2 hours from triage), early antibiotics (1–3 hours), early IV fluid (2.5–3 liters before starting EGDT), and early lactate measurement (30%–45% identified by lactate alone: normotension + lactate ≥ 4) (see Table 5). Institutions not having these protocols in place may not achieve equivalent findings.

(click for larger image)

Table 5: Summary of ProCESS, ARISE, and ProMISe: Components of Usual Care Resuscitation

Fluid Resuscitation

The guidelines recommend 30 mL/kg of fluid within the first three hours (strong recommendation, low quality of evidence). Denoting “low quality of evidence” demonstrates acknowledgement of limited data supporting this recommendation. This was a source of significant debate among committee members with strong opinions regarding the data on both sides. Data supporting the potential to do harm with excessive fluid administration were compared to data supporting potential harm regarding insufficient volume administration. Ultimately, it passed because, before randomization, ProCESS and ARISE used volumes consistent with 30 cc/kg and ProMISe used two liters in its usual care patient populations (see Table 5). Additionally, other observational evidence was supportive.10,11 However, growing information regarding diastolic dysfunction, right ventricular dysfunction, and obesity may require reconsideration of fluid volume in the next iteration.12,13 In most 70 kg patients, two liters may be a reasonable start. However, limited data exist in 300 kg patients; nine liters is potentially too aggressive.

Subsequent Hemodynamic Assessment

To summarize, after the initial fluid challenge, most physicians would reevaluate complex patients prior to administering more fluid (see Table 6). When available, use of dynamic over static variables for fluid responsiveness is advised.14 Finally, using CVP alone to determine fluid responsiveness is not justified. Emergency medicine in the United States is a leader in the use of ultrasound and other noninvasive strategies to direct emergent resuscitation. However, this is not consistent globally, where many clinicians struggle to provide the best care they can in resource-limited areas.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 5 | Single Page

5 Responses to “ACEP Endorses Latest Surviving Sepsis Campaign Recommendations”

March 31, 2017

John ReevesWell done review! Thank you so much – very helpful

April 2, 2017

Munish GoyalGreat work, Tiffany. This very nicely summarizes the different definitions, some of the confusion, and a logical path forward.

One thing caught my eye in table 1 — the established definition (CMS) of severe sepsis includes an elevated lactate (> 2.1 at my shop), not lactate > 4.

April 28, 2017

Dawn Antoline-WangThank you for pointing this out, Dr. Goyal. The table has been corrected.

March 18, 2018

Rushdi AlulHello Dr. Osborn,

I am an internist working in the Chicago area and I would like to commend you for writing such an excellent article. I am contacting you in regard to a comment in your article, specifically your recommendation to use the established definitions for sepsis used by CMS. My confusion is the following. I will see on a regular basis young adults, for example, a 21 year old male complaining of fever and sore throat and noted to have a heart rate >90 bpm. After examination if appropriate, I will perform a rapid strep test. Assuming the strep test is positive I will tell him he has strep throat and treat him accordingly. However he meets the CMS guideline for sepsis, is his correct diagnosis strep throat with sepsis?? I am reluctant to use sepsis in this scenario since I am accustomed to associating sepsis with patients who display evidence of clinical or hemodynamic instability (requiring resuscitative intervention) which this young man does not have nor need. Any clarification or insight you can provide would be greatly appreciated!

March 20, 2018

Rushdi AlulDr. Osborn,

I would like to commend you for writing such an excellent article. I am contacting you in regard to a comment in your article, specifically your recommendation to use the established definitions for sepsis used by CMS. My confusion is the following. I will see on a regular basis young adults, for example, a 21 year old male complaining of fever and sore throat and noted to have a heart rate >90 bpm. After examination if appropriate, I will perform a rapid strep test. Assuming the strep test is positive I will tell him he has strep throat and treat him accordingly. However he meets the CMS guideline for sepsis, is his correct diagnosis strep throat with sepsis?? I am reluctant to use sepsis in this scenario since I am accustomed to associating sepsis with patients who display evidence of clinical or hemodynamic instability (requiring resuscitative intervention) which this young man does not have nor need. Any clarification or insight you can provide would be greatly appreciated!