Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 36 – No 03 – March 2017(click for larger image)

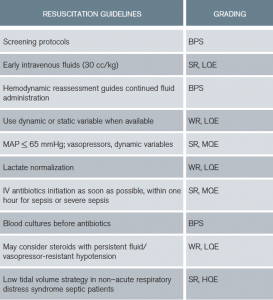

Table 6: Resuscitation Guidelines Summary

BPS = best-practice statement; SR = strong recommendation; WR = weak recommendation; HQE = high quality of evidence; MQE = moderate quality of evidence; LQE = low quality of evidence

Lactate

The guidelines suggest guiding resuscitation to normalize lactate. Serum lactate is not a direct measure of tissue perfusion. There are patient populations in which lactate may not represent physiologic decline, for example, those with decreased clearance (liver dysfunction) and type B lactic acidosis, such as with beta-adrenergic stimulation from endogenous or exogenous catecholamine (eg, epinephrine). In limited patient populations demonstrating consistent physiologic stability, persistent therapies focused on lactate reduction may not be beneficial. However, this is a diagnosis of exclusion to be evaluated within specific clinical context and should not be initially applied to patients presenting in distress. The data overwhelmingly support an association between hyperlactemia and mortality. Increased mortality is reported in patients with or without hypotension, and some data support a dose-response curve.15–18 Any lactate reduction is associated with sequential survival benefit in compromised patients and is the initial step toward the goal of normalization.

Antibiotics

The guidelines recommend IV antibiotic administration as soon as possible after recognition and within one hour for sepsis and septic shock (strong recommendation, moderate quality of evidence). This recommendation was based upon data demonstrating increased mortality for every hour of delay in antibiotic administration for infected patients with organ dysfunction and/or shock.19,20 These are patients in distress, most especially those in septic shock. However, a meta-analysis reported no benefit of rapid antibiotic administration. Although several poor-quality studies were included, the meta-analysis called into question the one-hour target. Ultimately, the recommendation of antibiotics within one hour for both sepsis and septic shock was considered “a reasonable minimal target” based upon the largest highest-quality studies in the meta-analysis. It is currently unclear, especially in sepsis compared to septic shock, if antibiotic administration within one hour is better than within three. Current Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) guidance is to administer antibiotics as soon as possible and within three hours of sepsis or septic shock diagnosis.

EGDT is no longer recommended. Specifically, given no benefit in the general population of septic patients, CVP, hematocrit, and ScvO2 goals are not encouraged.

Although the guideline-drafting process has improved, it still is subject to the weakness of human interpretation and available data at the time of analysis. Guidelines cannot replace clinical acumen or negate our responsibility to consider unique patient variables or physiology. Emergency medicine should continue to contribute innovation to the areas of resuscitation, including:

- The screening of infected patients for the potential of decline

- Fluid volume and time endpoints, including methods of fluid-responsiveness assessment

- Use of biomarkers, including lactate

- The impact of time to antibiotics with respect to severity of illness

Pages: 1 2 3 4 5 | Single Page

5 Responses to “ACEP Endorses Latest Surviving Sepsis Campaign Recommendations”

March 31, 2017

John ReevesWell done review! Thank you so much – very helpful

April 2, 2017

Munish GoyalGreat work, Tiffany. This very nicely summarizes the different definitions, some of the confusion, and a logical path forward.

One thing caught my eye in table 1 — the established definition (CMS) of severe sepsis includes an elevated lactate (> 2.1 at my shop), not lactate > 4.

April 28, 2017

Dawn Antoline-WangThank you for pointing this out, Dr. Goyal. The table has been corrected.

March 18, 2018

Rushdi AlulHello Dr. Osborn,

I am an internist working in the Chicago area and I would like to commend you for writing such an excellent article. I am contacting you in regard to a comment in your article, specifically your recommendation to use the established definitions for sepsis used by CMS. My confusion is the following. I will see on a regular basis young adults, for example, a 21 year old male complaining of fever and sore throat and noted to have a heart rate >90 bpm. After examination if appropriate, I will perform a rapid strep test. Assuming the strep test is positive I will tell him he has strep throat and treat him accordingly. However he meets the CMS guideline for sepsis, is his correct diagnosis strep throat with sepsis?? I am reluctant to use sepsis in this scenario since I am accustomed to associating sepsis with patients who display evidence of clinical or hemodynamic instability (requiring resuscitative intervention) which this young man does not have nor need. Any clarification or insight you can provide would be greatly appreciated!

March 20, 2018

Rushdi AlulDr. Osborn,

I would like to commend you for writing such an excellent article. I am contacting you in regard to a comment in your article, specifically your recommendation to use the established definitions for sepsis used by CMS. My confusion is the following. I will see on a regular basis young adults, for example, a 21 year old male complaining of fever and sore throat and noted to have a heart rate >90 bpm. After examination if appropriate, I will perform a rapid strep test. Assuming the strep test is positive I will tell him he has strep throat and treat him accordingly. However he meets the CMS guideline for sepsis, is his correct diagnosis strep throat with sepsis?? I am reluctant to use sepsis in this scenario since I am accustomed to associating sepsis with patients who display evidence of clinical or hemodynamic instability (requiring resuscitative intervention) which this young man does not have nor need. Any clarification or insight you can provide would be greatly appreciated!