Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 37 – No 04 – April 2018ILLUSTRATION: Chris Whissen PHOTOS: shutterstock.com

Shortening the time window of research knowledge to clinical application is one of the major aims of the Free Open-Access Medical Education (FOAMed) movement. When new research is published, it often takes years, and sometimes decades, for that information to trickle out into mainstream practice. That’s where FOAMed shows some of its greatest promise. In fact, FOAMed junkies might occasionally be accused of being the opposite of late-adaptors; many of our most enthusiastic FOAMed consumers have been criticized for adopting new ideas too quickly, based solely on a podcast or a blog that may have been based on a body of low quality research.

There’s probably some truth to that, but in reality, we haven’t heard too many stories about cases gone wrong because a physician was blindly following the advice of some joker with a blog or a podcast available on iTunes. In fact, we’ve found that FOAMed consumers tend to be the ones who are likely to be among the most informed when it comes to journals and text books, not just what’s free online. We’d like to think that’s because FOAMed encourages its users to go deeper than one podcast or a blog and inspires them to look carefully into a topic being discussed. Sometimes you find that what passes for “cutting-edge FOAMed” is actually a venerable treatment that, for some reason, has been supplanted by something shiny and new. In that spirit, in a recent episode of FOAMcast, we covered some FOAMed that advocated for the return of a tried-and-true treatment masquerading as progressive medicine for an emergency medical condition that we treat all the time: alcohol withdrawal.

Treatment History

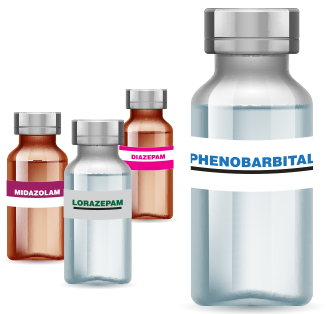

After the 1950s, benzodiazepines became the mainstay treatment for alcohol withdrawal and delirium tremens. However, a recent blog post on the Pulmcrit/Emcrit.org website, written by critical care physician Joshua Farkas, MD, made a fairly convincing argument for bringing back the previous mainstay of alcohol withdrawal treatment, phenobarbital. Many alcohol withdrawal protocols in use today include phenobarbital when the benzos just aren’t working. What Dr. Farkas is talking about is phenobarbital as monotherapy for alcohol withdrawal. Cool!

The beauty of using phenobarbital is that its dosing is far easier to keep straight. Rather than deciding among diazepam, lorazepam, or midazolam—perhaps after a failed trial of chlordiazepoxide (Librium)—and trying to guess how large a dose to give and how often, the phenobarbital monotherapy protocol seems to have an easier opening gambit. In patients with moderate to severe alcohol withdrawal who have not yet received benzodiazepines (or other sedatives) and appear to have alcohol withdrawal alone (ie, no other active neurologic problem), simply give 10 mg/kg (ideal body weight) intravenously over 30 minutes. Then wait 30 minutes. If after one hour, the patient still requires more medication, you can give 130 mg (for mild symptoms) or 260 mg (for moderate to severe symptoms) IV given over three to five minutes, as needed every 30 minutes. As long as the cumulative dose does not exceed 20 mg/kg IV, there is little risk. There are also oral and intramuscular strategies for maintenance. For that, check out emcrit.org/pulmcrit/phenobarbital-reloaded.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

No Responses to “Alcohol Withdrawal Treatment: Bring Back Phenobarbital?”