A DNR order refers to an actual physician order that directs providers not to intervene with CPR if patients are found pulseless or apneic.3,4 Unless patients have suffered a cardiac or respiratory arrest, the DNR order is not enacted.3,4 A POLST is a medical order set that is transferrable among various health care settings and, in some states, the pre-hospital setting. It requires a physician’s signature and is often completed by trained nonmedical personnel.5 This active order guides patients’ care when they are found in cardiac arrest as well as in non–cardiac arrest scenarios.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 33 – No 05 – May 2014Despite legal and societal definitions of DNR, TRIAD research reveals that medical providers understand DNR as synonymous with an order to provide comfort and end-of-life care.6-8 This raises serious concerns with providers’ understanding of how to carry out patients’ wishes.

Primary care physicians obtain initial DNR orders and guide advance-care planning, but they do so at a time when the situation and environment are too artificial for patients to fully consider the implications of their decisions. After all, if you are asked, “If your heart stops, do you want it restarted?” what would your response be? That question is far from a full, informed discussion about prognosis and what resuscitation entails. As emergency physicians, we are not involved in the informed-consent process of the DNR order or advance-directive completion. However, we are expected to honor them, even in critical situations, with seconds to minutes to save a life. This creates a situation compromising the safety of patients. Often, we are unaware of whether or not patients are terminally ill and are forced to choose instituting or withholding lifesaving care. If we are correct, then patients’ end-of-life wishes are honored, but if wrong, we may inappropriately resuscitate patients or, conversely, allow patients to die!

The American Bar Association has a POLST legislative guide created and approved by both the association and the National POLST Paradigm Task Force. It specifically recommends that POLST documents be reviewed periodically and specifically when: 1) patients are transferred from one care setting or care level to another; 2) there is a substantial change in patients’ health; or 3) patients’ goals or treatment preferences change.9 These requirements could easily apply to all types of advance directives, ensuring that patients’ wishes are met.

If we are correct, then patients’ end-of-life wishes are honored, but if wrong, we may inappropriately resuscitate patients or, conversely, allow patients to die!

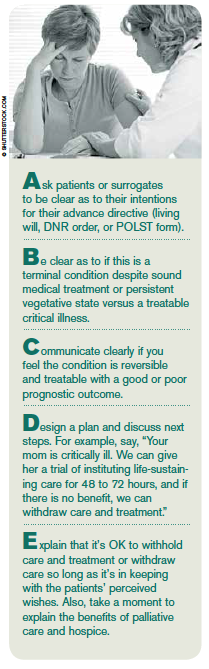

How can we operationalize such a requirement? Our institution uses the Resuscitation Pause, which combines the ABCs (Airway, Breathing, and Circulation) of resuscitation and a hospital process called the Time Out, or surgical pause. At the same time we are performing our initial ABCs, we run through our Resuscitation Pause checklist described in Table 1. This provides us with the opportunity to have an individualized discussion for patients and design an individualized plan of care. We recommend that this process and checklist be incorporated into resuscitations when confronted with all types of advance directives. Remember, resuscitation does not just apply to cardiac arrest patients! Resuscitation applies when patients present critically ill with respiratory distress, myocardial infarction, stroke, sepsis, trauma, gastrointestinal bleeding, etc. A safeguard such as the Resuscitation Pause allows the physician to clarify the intent of the advance directive or POLST and design that individualized plan of care to make sure we get it right for each patient and every time.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

No Responses to “Avoid Potential Pitfalls of Living Wills, DNR, and POLST with Checklists, Standardization”