For clarification, the living will’s presence does not mean it should be followed. It simply indicates that this document is “effective” (ie, it’s valid and legal).

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 33 – No 05 – May 2014

Until recently, the risks posed to patient safety by the various incarnations of advance directives were unknown and thus undisclosed, producing unintended consequences. The TRIAD (The Realistic Interpretation of Advance Directives) series of studies has disclosed this patient safety risk as reality on a nationwide scale. The risk is attributable to variable understanding and misinterpretation of advance directives, which then translates into over- or under-resuscitation.

So what limits advance directives? With 90 million of them in existence in the United States, these limitations can lead to deleterious effects on patient care and safety.1 These are a few of the more commonly cited limitations:

- Their use has been mandated but not funded.

- There is no standardization or clarification of terms.

- There is variable understanding among providers.

- They are often not available at the time of need.

- Informed discussion takes place in the primary care physician’s office.

Standardization is a powerful safety tool. In TRIAD III, high percentages of participants reported receiving training about advance directives, but they received no benefit. The most compelling reason is lack of standardization. To facilitate understanding, the following terms need to be defined and standardized:

- Terminal illness defined by law

- Reversible and treatable condition

- An “effective” living will

- An “enacted” living will

- Do not resuscitate (DNR) order

- Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) document

For clarification, the living will’s presence does not mean it should be followed. It simply indicates that this document is “effective” (ie, it’s valid and legal).2 An “enacted” or “activated” living will is one that has been activated by the triggers in the document, a terminal or end-stage medical condition, or a persistent vegetative state.2 This enacted living will now requires adherence to its instructions. Legally defined, a terminal or end-stage medical condition is when patients are expected to die of their disease process despite medical treatment. Therefore, the living will does not dictate the care of critically ill patients who present with a reversible and treatable condition such as congestive heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; rather, it applies when those same patients are permanently unconscious and have exhausted all treatment options.

A DNR order refers to an actual physician order that directs providers not to intervene with CPR if patients are found pulseless or apneic.3,4 Unless patients have suffered a cardiac or respiratory arrest, the DNR order is not enacted.3,4 A POLST is a medical order set that is transferrable among various health care settings and, in some states, the pre-hospital setting. It requires a physician’s signature and is often completed by trained nonmedical personnel.5 This active order guides patients’ care when they are found in cardiac arrest as well as in non–cardiac arrest scenarios.

Despite legal and societal definitions of DNR, TRIAD research reveals that medical providers understand DNR as synonymous with an order to provide comfort and end-of-life care.6-8 This raises serious concerns with providers’ understanding of how to carry out patients’ wishes.

Primary care physicians obtain initial DNR orders and guide advance-care planning, but they do so at a time when the situation and environment are too artificial for patients to fully consider the implications of their decisions. After all, if you are asked, “If your heart stops, do you want it restarted?” what would your response be? That question is far from a full, informed discussion about prognosis and what resuscitation entails. As emergency physicians, we are not involved in the informed-consent process of the DNR order or advance-directive completion. However, we are expected to honor them, even in critical situations, with seconds to minutes to save a life. This creates a situation compromising the safety of patients. Often, we are unaware of whether or not patients are terminally ill and are forced to choose instituting or withholding lifesaving care. If we are correct, then patients’ end-of-life wishes are honored, but if wrong, we may inappropriately resuscitate patients or, conversely, allow patients to die!

The American Bar Association has a POLST legislative guide created and approved by both the association and the National POLST Paradigm Task Force. It specifically recommends that POLST documents be reviewed periodically and specifically when: 1) patients are transferred from one care setting or care level to another; 2) there is a substantial change in patients’ health; or 3) patients’ goals or treatment preferences change.9 These requirements could easily apply to all types of advance directives, ensuring that patients’ wishes are met.

If we are correct, then patients’ end-of-life wishes are honored, but if wrong, we may inappropriately resuscitate patients or, conversely, allow patients to die!

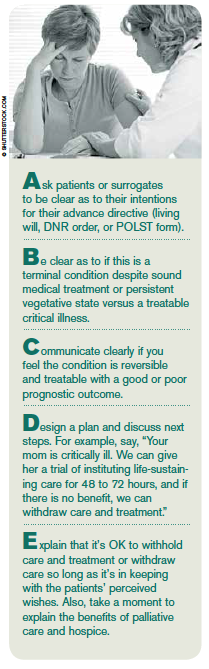

How can we operationalize such a requirement? Our institution uses the Resuscitation Pause, which combines the ABCs (Airway, Breathing, and Circulation) of resuscitation and a hospital process called the Time Out, or surgical pause. At the same time we are performing our initial ABCs, we run through our Resuscitation Pause checklist described in Table 1. This provides us with the opportunity to have an individualized discussion for patients and design an individualized plan of care. We recommend that this process and checklist be incorporated into resuscitations when confronted with all types of advance directives. Remember, resuscitation does not just apply to cardiac arrest patients! Resuscitation applies when patients present critically ill with respiratory distress, myocardial infarction, stroke, sepsis, trauma, gastrointestinal bleeding, etc. A safeguard such as the Resuscitation Pause allows the physician to clarify the intent of the advance directive or POLST and design that individualized plan of care to make sure we get it right for each patient and every time.

Dr. Mirarchi is medical director of the department of emergency medicine at UPMC Hamot and chair of the UPMC Hamot Physician Network in Erie, Pa.

Dr. Mirarchi is medical director of the department of emergency medicine at UPMC Hamot and chair of the UPMC Hamot Physician Network in Erie, Pa.

References

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2044 Population Estimates, Census 2000, 1990 Census. www.census.gov.

- Mirarchi FL. Understanding Your Living Will. Omaha, Neb: Addicus Books; 2006.

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Do not resuscitate (DNR) protocols within the Department of Veterans Affairs. Section 30.02. VHA Handbook. Available at: www.va.gov.

- AMA Code of Medical Ethics. Opinion 2.22 Do-Not-Resuscitate Orders. AMA Web site. Available at: www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics/opinion222.shtml. Accessed April 21, 2014.

- California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform. POLST problems and recommendations. Approved 2010. California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform Web site. Available at: www.canhr.org/reports/2010/POLST_WhitePaper.pdf. Accessed April 9, 2014.

- Mirarchi FL, Hite LA, Cooney TE. TRIAD I–the realistic interpretation of advanced directives. J Patient Saf. 2008;4:235-240.

- Mirarchi FL, Kalantzis S, Hunter D. TRIAD II: do living wills have an impact on pre-hospital life saving care? J Emerg Med. 2009;36:105-115.

- Mirarchi FL, Costello E, Puller J, et al. TRIAD III: nationwide assessment of living wills and DNR orders. J Emerg Med. 2012;42:511-520.

- National POLST Paradigm Task Force. POLST legislative guide. POLST Web site. Available at: http://www.polst.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/2014-02-20-POLST-Legislative-Guide-FINAL.pdf. Accessed April 9, 2014.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Avoid Potential Pitfalls of Living Wills, DNR, and POLST with Checklists, Standardization”