Children, for whatever reason, have a predilection for swallowing coins. Perhaps it’s the taste or that they’re using their stomach as a piggy bank. When these young patients present to the emergency department with a coin lodged in their esophagus, what options do we have? We could call gastroenterology or try to take it out ourselves. One option with few complications is bougienage, where we manually advance the coin into the stomach classically using a Hurst dilator and allow it to pass naturally.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 34 – No 05 – May 2015

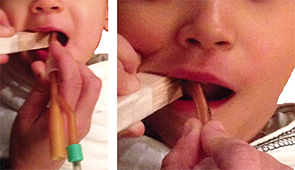

Figure 1. Tongue depressors taped together to act as a bite block

Background

In 2012, there were approximately 93,000 cases of foreign-body ingestions, nearly 4,000 of which were coins.1 While the feared button-battery ingestion can cause esophageal necrosis in as little as two hours, impacted coins can also cause perforation, obstruction, or fistulas if left untreated.2,3

The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) currently recommends an observation period of 24 hours for asymptomatic patients to see if the coin will pass into the stomach without any intervention.4 Up to 56 percent of coins lodged in the distal esophagus and 27 percent in the proximal esophagus will pass into the stomach without any complications.5 Once in the stomach, most coins will transverse the gastrointestinal

Figure 2. Hurst dilator

tract spontaneously.5,6 If the coin is retained within the stomach for more than three to four weeks, the patient will likely need endoscopic removal. The same is true for any coin that remains stationary for one week past the duodenum; it will need surgical removal.

For coins that do not spontaneously pass into the stomach, endoscopy has shown to be very successful (100 percent), with a small but measurable rate of complications, which are predominantly airway related (2.5 percent).7 An additional method of removal is using the Foley catheter technique. There are variations to the actual procedure, but typically it involves placing a Foley catheter (either orally or nasally) past the foreign body, inflating the Foley balloon, and extracting the foreign body. As you may imagine, the most concerning aspect to this technique is the thought of dragging the foreign body right past the glottis, which is just lying there open and waiting for that coin to drop in as though you are playing the penny slots in Vegas. While the concern is valid, the complication rate is relatively low (0–2 percent), and the success rate is favorable (88–94 percent).7–12

Data on the use of glucagon in impacted esophageal coins is relatively sparse. In 2001, Mehta et al prospectively evaluated the use of glucagon and found it to be ineffective in dislodging impacted esophageal coins.13 While the study was double-blind and placebo-controlled, the enrollment of only 14 patients limits its applicability and influence. Emergency physicians, at this point, cannot endoscopically remove a coin, and most of the published literature surrounding Foley catheter removal is done by other specialties (ie, otolaryngology, gastroenterology, surgery). When the right patient is selected, bougienage is a low-risk, highly successful alternative to the previously mentioned interventions and one we can employ in the emergency department.

Bougienage

Bougienage has been around for decades, but it remains an infrequently used modality for the treatment of retained esophageal coins.14 In the correctly selected patient, as detailed in Table 1, bougienage has a success rate of 83–100 percent in advancing the coin into the patient’s stomach.14–18 Among larger studies with more than 100 patients undergoing bougienage, the success rate is 94–95.4 percent.15,19 Rigid adherence to the inclusion criteria maintains bougienage as a reliable modality. However, when not following these criteria, the success rate drops to 75 percent, as Allie et al demonstrated in their 2014 article.15

Figure 3. Insertion of the apparatus into the oropharynx.

Written parental consent was obtained for this simulated procedure. Additionally, this demonstrates that if your child is guilty of pocketing a quarter, you could go after it in the comfort of your own home.

Perhaps more important, throughout the previous studies, complications directly related to bougienage are nearly unheard of. Arms et al attempted bougienage on 372 patients, two of whom had the complication of intraoral abrasions from the bite block used during the procedure.19 Additionally, Allie et al demonstrated a minor complication rate of 16.8 percent in their 137 bougienage attempts.15 The majority of these minor complications resulted from vomiting, gagging, or the need for repeat bougienage, without major complications noted. To the best of our knowledge, there has not been a documented serious or life-threatening complication from attempted bougienage.14–19 In addition to the safety and efficacy of bougienage, there have been numerous reports of the decreased cost and length of stay with bougienage versus endoscopy. The length of stay is decreased 4–20 hours and is associated with a decrease in cost of $1,890–$6,000.15–17,19,20 This procedure is not limited to otolaryngology, gastroenterology, or surgery; trained emergency physicians have proven that we, too, can bougienage with the best of them, with success rates of 94–100 percent.14,18,19

Bougienage Procedure

Equipment

- Tape measure

- Tongue depressors (approximately 5–6) taped together to act as a bite block (Figure 1)

- Hurst dilator (Figure 2) or alternative as described here.

- Topical anesthetic (ie, benzocaine spray)

- Water-based lubricant

Procedure

- Confirm that the patient has an esophageal coin with a two-view radiograph and that the patient meets the criteria for bougienage (see Table 1).

- Measure the distance from the patient’s nares to the epigastrium and mark this distance on the Hurst dilator to approximate how far to insert the dilator.

- Topically anesthetize the patient with benzocaine spray.

- Sit the patient upright with a sheet held tightly around the patient and with either an assistant or a parent holding the patient’s head still by the forehead.

- The makeshift bite block constructed earlier can now be inserted to protect the Hurst dilator and allow unobstructed entry of the Hurst dilator into the oropharynx.

- Place a liberal amount of water-based lubricant on the Hurst dilator, or the alternative device, and insert it into the oropharynx (see Figure 3). Advance it until you reach the mark you placed on the dilator. If, at any time, you encounter resistance, stop the procedure.

- Remove the dilator and take another radiograph to determine the new location of the coin.

- If the coin remains in the esophagus, the patient can undergo another attempt at bougienage at the discretion of the provider. If still unsuccessful, you will need to contact your gastroenterology colleagues.

- If the coin is now in the stomach, the patient can be observed for a short time in the emergency department and then discharged home with detailed follow-up instructions.

Follow-up

After a successful bougienage with passage of the coin into the stomach, the patient can be discharged home. The patient’s parents need to be extensively educated on the need to return to the emergency department with any concerning symptoms. Despite the lack of known serious complications following bougienage, the parents should be monitoring for abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, chest pain, constipation, obstipation, fever, chills, or any other concerning signs of obstruction or perforation. The parents also have the privilege of checking all of the patient’s bowel movements for passage of the coin; if by two weeks they have not noticed passage of the coin, a repeat radiograph may be warranted.

Dr. McGovern is an emergency medicine resident at St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center in Paterson, New Jersey.

Dr. McGovern is an emergency medicine resident at St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center in Paterson, New Jersey.

Dr. McNamee is chief resident of the emergency medicine residency at St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center in Paterson, New Jersey.

Dr. McNamee is chief resident of the emergency medicine residency at St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center in Paterson, New Jersey.

Dr. Sanicola-Johnson is director of physician wellness and an emergency medicine attending physician/EMS physician at St. Joseph’s Regional Medical Center in Paterson, New Jersey.

References

- Mowry J, Spyker J, Cantilena L, et al. 2012 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System: 30th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol. 2013;51:949-1229.

- Eisen G, Baron T, Dominitz A, et al. Guideline for the management of ingested foreign bodies. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55(7):802-806.

- National Capital Poison Center. Mechanisms of battery-induced injury. National Capital Poison Center Web site. Available at: http://www.poison.org/battery/mechanism.asp. Accessed January 20, 2015.

- Ikenberry S, Jue T, Anderson M, et al. Management of ingested foreign bodies and food impactions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73(6):1085-1091.

- Waltzman M, Baskin M, Wypij D, et al. A randomized clinical trial of the management of esophageal coins in children. Pediatrics. 2005;116:614-619.

- Conners G, Chamberlain J, Ochesenschlager D. Conservative management of pediatric distal esophageal coins. J Emerg Med. 1996;14(6):723-726.

- Conners G. A literature-based comparison of three methods of pediatric esophageal coin removal. Ped Emerg Care. 1997;13(2):154-157.

- Hawkins D. Removal of blunt foreign bodies from the esophagus. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1990;99(12):935-940.

- Campbell J, Condon V. Catheter removal of blunt esophageal foreign bodies in children. Survey of the Society for Pediatric Radiology. Pediatr Radiol. 1989;19(6-7):361-365.

- Schunk J, Harrison A, Corneli H, et al. Fluoroscopic Foley catheter removal of esophageal foreign bodies in children: experience with 415 episodes. Pediatrics. 1994;94 (5):709-714.

- Chen M, Beierle E. Gastrointestinal foreign bodies. Pediatr Ann. 2001;30(12):736-742.

- Little D, Shah S, St Peter S, et al. Esophageal foreign bodies in the pediatric population: our first 500 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:914-918.

- Mehta D, Attia M, Quintana E, et al. Glucagon use for esophageal coin dislodgement in children: a prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:200-203.

- Bonadio W, Jona J, Glicklich M, et al. Esophageal bougienage technique for coin ingestion in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1988;23(10):917-918.

- Allie E, Blackshaw A, Losek J, et al. Clinical effectiveness of bougienage for esophageal coins in a pediatric ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:1263-1269.

- Calkins C, Christians K, Sell L. Cost analysis in the management of esophageal coins: endoscopy vs bougienage. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34(3):412-414.

- Dahshan A, Donovan K. Bougienage versus endoscopy for esophageal coin removal in children. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41(5):454-456.

- Emslander H, Bonadio W, Klatzo M. Efficacy of esophageal bougienage by emergency physicians in pediatric coin ingestion. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;27(6):726-729.

- Arms J, Mackenberg-Mohn M, Bowen M, et al. Safety and efficacy of a protocol using bougienage or endoscopy for the management of coins acutely lodged in the esophagus: a large case series. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:367-372.

- Soprano J, Mandl K. Four strategies for the management of esophageal coins in children. Pediatrics. 2000;105(1):1-5.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Bougienage Good Alternative for Treating Retained Esophageal Coins”