Washington Hospital Healthcare System (WHHS) in Fremont, California, had a very efficient emergency department that had long ago outgrown its physical plant. Seeing more than 150 patients per day in its 28-bed department, it was a model of efficiency. Though adjacent spaces had been repurposed—including using a modular building for triage to free up the previous triage and registration area for a fast track to help manage patient flow—it still boasted very strong patient flow metrics:

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 38 – No 03 – March 2019Initial Metrics

Door to Provider: 27 minutes

- Length of Stay (LOS) Overall: 198 minutes

- LOS Admitted: 262 minutes

- LOS Discharged: 143 minutes

- Left Without Being Seen: 1.45 percent

The old emergency department had a very small footprint (7,600 square feet), so the ED leaders and staff were forced to be efficient in storing the supplies and equipment necessary to run a busy emergency department. The tight layout made communication very easy, as everyone was within voice distance. After years of planning, the board came up with funding to build a new acute care tower, which would house the emergency department, the intensive care units (ICUs), and inpatient rooms. The acute care tower included a 22,000-square-foot emergency department (three times the original emergency department size), allowing for a number of different patient flow models. The WHHS leaders left nothing to chance. They began planning for the move to the new tower more than a year in advance.

Careful Planning

Working with an independent consultant, the leaders assembled a multidisciplinary transition team that was very engaged in the process. Many of the participants in the transition work had survived another move into a new emergency department in northern California and were eager to avoid the mistakes that frequently plague moves of this kind. For example, one team member moved into a new department where the phone system did not work! They were determined to plan carefully.

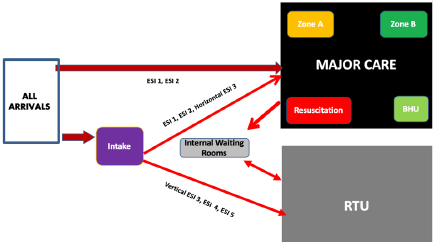

The team began with a data analysis that helped inform the patient flow model that could be fitted into the new space. With a high volume of low-acuity patients in their mix, the team decided on this elegant flow model for their emergency department (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Patient flow model for Washington Hospital Healthcare System’s new emergency department.

In the new model, ambulances, 21 percent of arrivals, would typically be screened by the charge nurse and quickly assigned to either major care (bedded patients) or the rapid treatment unit (RTU) for low-acuity patients. Emergency Severity Index 3 patients who needed a bed could have their medical screening exam and testing started in the RTU and then be sent to one of the zones. The new emergency department had a designated behavioral health care area and two large trauma/resuscitation bays for a total of 40 treatment spaces. The RTU had six rooms plus its own internal waiting room.

The transition team developed a robust work plan with all that needed to be done prior to the move into the department. The transition team had exceptional leadership that included the physician medical director, Kadeer Halimi, DO, and nursing leaders Michael Platzbecker, MSN, RN, CEN, assistant chief nursing officer, and Brenda Brennan, MS, RN, CNS, CEN, emergency services administrator. They had high-level executive support from their CEO, Nancy Farber, and their chief nursing officer, Stephanie Williams. Many of the staff who worked in the emergency department participated in this transition work so a critical mass of people was invested. Checklists for supplies for each area were developed. Because communication would now be a challenge in the bigger emergency department, a workgroup was formed to look at the specifications and features of various communication devices, and the group partnered with the ICU in selecting a device.

One of the challenges for the transition team was the development of zones using the existing geography. Unfortunately, the model that had been developed by physicians more than a decade prior was not created with geographic work zones in mind, a newer design concept for emergency medicine. Creating work zones for medical teams proved difficult, as the layout could not be easily divided into zones. The transition team, along with physician and nurse leaders, worked steadfastly in cooperation to develop these zones. Realizing that some patients are more complex and some providers are faster than others, the physicians and nurses opted for a flex zone in the department. They adhere to a strict patient-centric culture in the WHHS emergency department, and the physicians are highly productive. They believe that if a provider is available and a patient needs to be seen, there should be flexibility in the system. Their model allows for flexing of zones based on patient need. This was a big change for all stakeholders. In the smaller department, the physicians used free-range staffing to self-assign patients, and there were no zones. In the new department, the zones are fed by the charge nurse, who functions as a flow nurse. Rules of the road were crafted to help standardize patient streaming and flow into the zones. Additionally, the physician group has kept some of its older physicians on staff to work four-hour “swing shifts” when the department is on surge.

The WHHS transition team met monthly to work on all the elements of their transition work plan. Tabletop exercises were conducted to validate that their flow model would work. Using real patient data from the year before, they tested the flow model using these exercises, informed by actual patient demographic and chief complaint data to validate their model. During construction, the transition team made regular visits to the new space to give input on nonstructural decisions like computer and phone placement. Toward the end of the build, the transition team began intense training for the staff on patient flow and new processes. There were tutorials regarding supply locations, travel throughout the department, patient streaming, and all operational details. Exact patient flow through the department was mapped, and the staff received this training as well.

Finally, the transition team conducted several days of mock patient encounters, with registration and ancillary services present. Interesting small changes were identified. Patient intake was challenging due to a bulletproof window that did not allow for communication with arriving patients and families. This was addressed by adding an intercom. The imaging department developed the details for patients being transported to imaging. Ultrasound opted to bring the ultrasound machine to the emergency department for formal ultrasounds rather than transporting patients out of the department.

Celebrating Success

All of this preparation led to a seamless opening day, and within a week, the WHHS emergency department was performing better than it did prior to the change. Door-to-physician times were seven minutes, and patient walkaways all but disappeared.

Current State Metrics

- Door to Provider: 9 minutes

- LOS Overall: 164 minutes

- LOS Admitted: 286 minutes

- LOS Discharged: 133 minutes

- Left Without Being Seen: 0.5 percent

For anyone looking forward to a moving day, it is never too early to start the transition work. The WHHS transition team led one of the most successful emergency department relocations I have heard of. The time spent helped the team to maintain a high-functioning and cohesive unit that was able to problem-solve as new situations arose. They are now such a high-performing team that they are ready for their next challenges: The WHHS ED leaders are maintaining their magnet status while planning to become a designated trauma center for their region! Hats off to the WHHS transition team.

Pages: 1 2 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Careful Planning and Innovation Helped Washington Hospital Move Its Emergency Department”