Our patient is a 33-year-old male with spastic quadriparesis due to cerebral palsy with chronic indwelling suprapubic catheter (SPC) who presented to the emergency department (ED) due to concern for Foley catheter obstruction. The patients’ mother has attempted to flush the SPC multiple times unsuccessfully at home. The catheter was reportedly due for an exchange the following week. The patient reports pain at the site of SPC but denied fevers, nausea, vomiting, or other systemic symptoms. SPC was exchanged in the ED with clear yellow fluid observed draining into the bag.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 43 – No 10 – October 2024The patient was discharged with return precautions; however, he returned nine days later with a migraine, emesis, and fever (38 C) at home. At the time of evaluation, all symptoms had resolved. The SPC was able to be flushed and laboratory evaluation included blood count, metabolic panel and urinalysis, all of which were unremarkable other than suspicion for urinary bacterial colonization. The patient was ultimately discharged home with return precautions and the SPC was not exchanged. Two days later, the patient returned for a third time with a fever and new, sharp left flank pain.

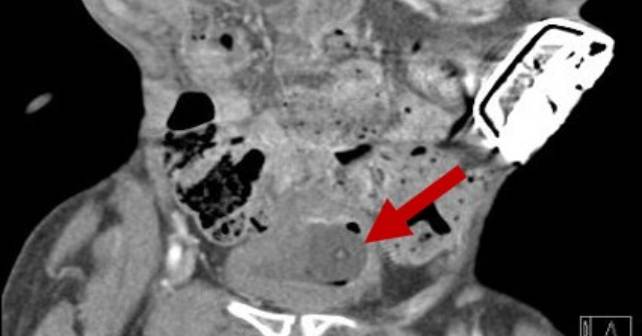

A CT abdomen and pelvis with contrast was obtained on the third visit revealing hydroureter and hydronephrosis with signs of pyelonephritis related to ureteral obstruction from the Foley catheter. At this presentation, the patient demonstrated fever at 39.3 degrees Celsius, an elevated white blood cell count, and was toxic appearing. The patient was started on antibiotics covering Klebsiella species (grown from urine culture obtained during the first visit) and the SPC was immediately replaced with confirmation of placement into the bladder with ultrasound. Intravenous fluids, blood cultures, and repeat laboratory evaluation were performed. There was no significant kidney injury; the patient remained hemodynamically stable and was admitted to the medical service.

Discussion

Bladder indwelling catheters (BICs) carry a significant risk for injury and infection. The most common complications are urethral trauma and catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Placement of an SPC is more complex, and places patients at risk for complications not seen with BICs. More common complications include abdominal organ injury, hematuria, spasms, and stone formation, with a mortality risk of up to 2.4 percent.1,2 Rare yet severe complications may also occur including ureteral obstruction, ureteral rupture, and bladder prolapse. Many of these complications have limited support on proper management due to their low prevalence. There are only 35 known cases of accidental placement in the ureter (27 from BIC, 8 from SPC), with no significant difference with respect to laterality.3 There have also been case reports of the catheter balloon being inflated in the ureter causing ureteral rupture requiring urgent operative intervention.3 Luckily, in the case of our patient, the SPC had a longer tip, and the balloon was still in the bladder when inflated.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

No Responses to “Case Report: A Male Patient with Iatrogenic Obstruction”