The Case

A 35-year-old white woman presented to the emergency department with a chief complaint of chest pain. She stated the chest pain began acutely, about 15 minutes prior to her arrival. The pain was sharp; radiated to her left arm; and was not accompanied by nausea, vomiting, fever, or chills. She had not missed any of her daily medications and had never experienced this type of discomfort before. She had no history of pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 40 – No 05 – May 2021The patient’s past medical history was significant for transposition of the great vessels, which required surgical repair at 4 months of age (a Senning procedure). She was known to have severe right ventricular (RV) dysfunction and was awaiting transplant workup. She also had a history of diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, atrial fibrillation, atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia (requiring previous ablation), and cardiac arrest with subsequent placement of an automated implantable cardioverter defibrillator. Her medications included rivaroxaban, insulin glargine, dulaglutide, levothyroxine, lisinopril, spironolactone, and metoprolol.

On exam, she was an obese woman who appeared slightly uncomfortable but in no acute distress. Vital signs were unremarkable: blood pressure 98/61, heart rate 84, temperature 97.3ºF, respiratory rate 18, and oxygen saturation 95 percent on room air. She had normal speech and mental status and had no diaphoresis. Her lungs were clear. A cardiac examination was normal. There was no pitting edema.

Figure 2: The patient’s initial ECG 10 minutes after presentation.

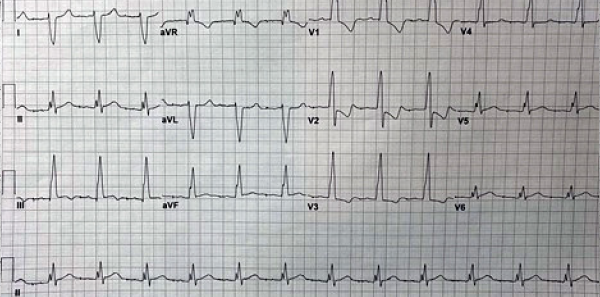

Her initial electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrated an atrially paced rhythm with prolonged atrioventricular (AV) conduction and a bifascicular block, also evident on an ECG obtained one year prior to this incident (see Figures 1 and 2). Notably, the ST depression expected in the anterior leads with a right bundle branch block (RBBB) were changed, with less ST depression in V3 than before and no ST depression noted in V4. Though no pronounced ST elevations or depressions were noted, these findings were changes from the patient’s most recently known baseline and expected discordance in the ST segment in RBBB.

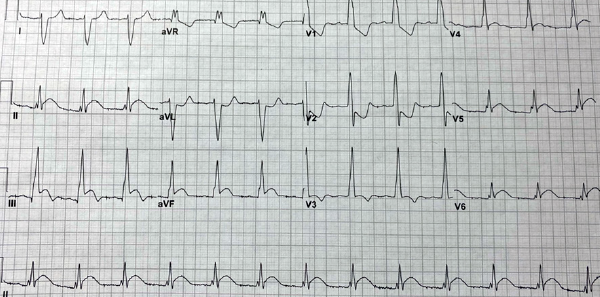

Figure 3: The patient’s ECG prior to cardiac catheterization, one hour after the initial ECG.

Alexandra Ferguson

Standard labs were obtained, with a complete blood count and basic metabolic panel within normal limits. A high-sensitivity initial troponin was normal.

At one hour, although her chest pain remained unchanged, her repeat troponin was elevated at 73 ng/L, up from 13 ng/L initially. A repeat ECG demonstrated ST segment elevations in leads II, III, AVF, and V6, with ST depression in V1 and V2 (see Figure 3). Given the concern for acute coronary syndrome (ACS), the patient was given a 324 mg dose of aspirin, intravenous heparin bolus, and infusion. She was seen by cardiology and was taken for emergent cardiac catheterization.

Cardiac catheterization demonstrated a complete embolic occlusion of the apical left anterior descending artery supplying the systemic right ventricle. Severe dilation of the right ventricle was also noted. The distal location of the embolus was not amenable to percutaneous coronary intervention.

The patient remained hemodynamically stable, and the decision was made to continue her on a heparin infusion and transfer her to the tertiary care facility for advanced cardiac care. There, she was evaluated for heart transplantation due to her worsening right ventricular dilation and systolic function.

Discussion

ACS includes a spectrum of illness, encompassing several types of NSTEMIs (non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarctions) and STEMIs (ST segment elevation myocardial infarctions).2 NSTEMIs result when there has been enough ischemia to the myocardium that myocardial cells are injured and begin to leak intracellular contents that may be measured in the blood (eg, troponin, creatine kinase, etc.).1,3 In contrast, STEMIs result most commonly from total occlusion of a coronary vessel, typically from a ruptured atherosclerotic plaque. STEMIs are suspected by a specific set of criteria on ECG tracings, including:4

- New ST elevation at the J point in two contiguous leads with f >0.1 mV in all leads other than leads V2–V3

- For leads V2–V3, ≥0.2 mV in men ≥40 years, ≥0.25mV in men <40 years, or ≥0.15 mV in women

- New left bundle branch block (in some cases, especially with Sgarbossa criteria)5

Regardless of the cause, restoring perfusion and oxygen supply to the myocardium is critical and time-dependent, making rapid diagnosis essential.

Although there are relatively clear diagnostic criteria to indicate STEMI, actual ECG findings can vary widely depending on the characteristics of the infarct (ie, size, severity, and timing) as well as when the ECG was obtained. In the patient described above, at the time of presentation, STEMI criteria were absent.

Riley and colleagues conducted a retrospective study in 2013 that evaluated 41,560 patients from 432 sites and found that 11 percent of patients who were ultimately diagnosed with STEMI did not meet STEMI criteria at the time of the initial ECG. They noted that 72.4 percent of this group developed diagnostic ECGs for STEMI on repeat testing obtained within 90 minutes. Further analysis of these populations showed no significant difference in the timing of the initial ECG being obtained in relation to symptom onset and no significant difference in coronary artery disease risk factors between the population who had initially diagnostic ECGs for STEMI and those who did not.6

Meanwhile, a paradigm shift in ACS may be under way. Meyers and colleagues conducted a retrospective study that reviewed a prospectively collected population of 467 ACS patients. The researchers compared two paradigms: occlusion with STEMI and occlusion without STEMI. Occlusion myocardial infarction (OMI) was defined as acute with either Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 0–2 flow or TIMI 3 flow plus peak troponin T >1.0 ng/mL. The results demonstrated that among 108 OMIs, only 60 percent met the usual STEMI criteria. Therefore, the study suggested that about 40 percent of OMIs did not present with STEMI criteria; those with STEMI plus OMI were more likely to go to a catheterization lab sooner than STEMI without OMI, though adverse outcomes were similar.7

Summary

This case describes a patient who presented with symptoms concerning for ACS. Repeat ECGs and troponin demonstrated myocardial ischemia that was not previously apparent.

It is widely known that ACS may be present without an initial increase in cardiac troponin if there has not been sufficient time. Many patients may be experiencing an acute STEMI without classic diagnostic ECG changes. Because the time to reperfusion is critical, it is important to obtain serial ECGs to reevaluate patients presenting with ACS symptoms.8

New studies have challenged the STEMI/NSTEMI model to include additional patterns in order to prevent delay in intervention of occlusion without STEMI.

Dr. Ferguson is a PGY-3 emergency medicine resident at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio.

References

- Hillis GS, Fox KA. Cardiac troponins in chest pain can help in risk stratification. BMJ. 1999;319(7223):1451-1452.

- Hwang C, Levis JT. ECG diagnosis: ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Perm J. 2014;18(2):e133.

- Kumar A, Cannon CP. Acute coronary syndromes: diagnosis and management, part I. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(10):917-938.

- Nikus K, Birnbaum Y, Eskola M, et al. Updated electrocardiographic classification of acute coronary syndromes. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2014;10(3):229-236.

- Wilner B, de Lemos JA, Neeland IJ. LBBB in patients with suspected MI: an evolving paradigm. American College of Cardiology website. Accessed March 16, 2021.

- Riley R, Mccabe J. ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: challenges in diagnosis. US Cardiol Rev. 2016;10(2):91-94.

- Meyers HP, Bracey A, Lee D, et al. Comparison of the ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) vs. NSTEMI and occlusion MI (OMI) vs. NOMI paradigms of acute MI. J Emerg Med. 2021;60(3):273-284.

- Silber SH, Leo PJ, Katapadi M. Serial electrocardiograms for chest pain patients with initial nondiagnostic electrocardiograms: implications for thrombolytic therapy. Acad Emerg Med. 1996;3(2):147-152.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Case Report: Acute Coronary Syndrome Symptoms Require Repeat ECGs”