A 46-year-old female with a prior medical history of asthma presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath and wheezing. After three DuoNeb treatments and 16 mg of dexamethasone, her wheezing improved; however, she continued to report shortness of breath on exertion. Given the persistent symptoms, a cardiac point-of-care ultrasound was obtained.

Explore This Issue

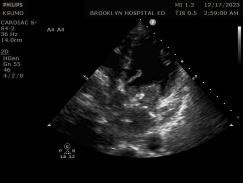

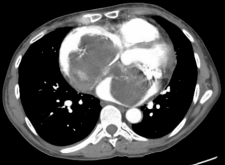

ACEP Now: Vol 43 – No 12 – December 2024Findings showed an irregularly shaped mobile heterogeneous echo-texture mass within the left atrium and a similar yet larger structure in the right atrium (see figures 1 and 2). Consequently, a CT chest angiogram was performed that confirmed the cause of her cardiac wheeze: a large bilobed mass, involving the right and left atrium, that appeared to extend through a large atrial septal defect (see figure 3).

Atrial myxomas have been known to present with a wide range of nonspecific symptoms. These symptoms can range from seemingly benign, such as cough or fatigue, to more concerning symptoms, such as dyspnea or edema. Given the wide range of clinical symptoms, the rate-limiting step for diagnosing atrial myxomas appears to be considering them in the first place. In our case, a patient with a long-standing smoking history and asthma presented with wheezing and shortness of breath. Such a clinical presentation can make it easy for an emergency physicians to anchor on asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder exacerbation. However, as seen in our case, not everything that wheezes is asthma.

Discussion

Primary cardiac tumors are rare, with an incidence of approximately 0.02 percent.

Most commonly, these masses arise in the left atrium, whereas, right atrial masses are more typically thrombi; however, biatrial masses have only rarely been reported in the literature.1

The classic triad of presentation of myxomas includes mitral valve obstruction, distal embolization, and constitutional symptoms. The most common symptoms of mitral valve obstruction were reported only in 67 percent of cases. The classic “tumor plop” sound on physical examination is not present in all cases.2 As these presenting symptoms are rare and nonspecific, an important clue for an emergency department physician lies in a thorough history and skin exam.

Although myxomas are typically idiopathic, about 10 percent are found in the autosomal-dominant Carney complex, a rare autosomal-dominant neuroendocrine–cardiac disorder that presents with recurrent myxomas, pigmented skin lesions, and schwannomas.3 Transthoracic echocardiography is typically the primary diagnostic imaging tool. The characteristic appearance on transthoracic echocardiography is a large pedunculated mass with lucencies and a stalk attached to the fossa ovalis. Surgical resection is the treatment of choice given the cardiac complication and embolization risk with myxomas.4

Dr. Ram is clinical research director at The Brooklyn Hospital Center, Brooklyn, N.Y.

Dr. Ram is clinical research director at The Brooklyn Hospital Center, Brooklyn, N.Y.

Dr. Darkwa is a PGY 3 emergency medicine resident at The Brooklyn Hospital Center, Brooklyn, N.Y.

Dr. Darkwa is a PGY 3 emergency medicine resident at The Brooklyn Hospital Center, Brooklyn, N.Y.

Dr. Sumon is director of emergency ultrasound at The Brooklyn Hospital Center, Brooklyn, N.Y.

Dr. Sumon is director of emergency ultrasound at The Brooklyn Hospital Center, Brooklyn, N.Y.

References

- Reynen K. Frequency of primary tumors of the heart. Am J Cardiol. 1996;77(1):107.

- Gupta P, Kapoor A, Jain M, et al. A butterfly shaped mobile biatrial cardiac mass: myxoma or something else. Indian Heart J.2014;66(3):372-374.

- Shetty Roy AN, Radin M, Sarabi D, et al. Familial recurrent atrial myxoma: Carney’s complex. Clin Cardiol.2011;34(2):83-86.

- Pinede L, Duhaut P, Loire R. Clinical presentation of left atrial cardiac myxoma: a series of 112 consecutive cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2001;80(3):159-172.

Pages: 1 2 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Case Report: Biatrial Myxoma in a 46-Year-Old Female”