A 10-year-old male with a past medical history significant for autism spectrum disorder and 15q3 deletion, experienced a cardiac arrest at home. There was no family history of syncope or sudden death. EMS found the patient pulseless and apneic, with an initial rhythm showing ventricular fibrillation (see figure 1). He was defibrillated twice and received two doses of epinephrine, with return of spontaneous circulation.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 43 – No 10 – October 2024Initial echocardiogram (ECG) on arrival (see figure 2) to our emergency department revealed normal sinus rhythm, mild interventricular conduction delay (RSR’), and possible right ventricular hypertrophy. This ECG in combination with presenting symptom of cardiac arrest raised suspicion for Brugada syndrome.

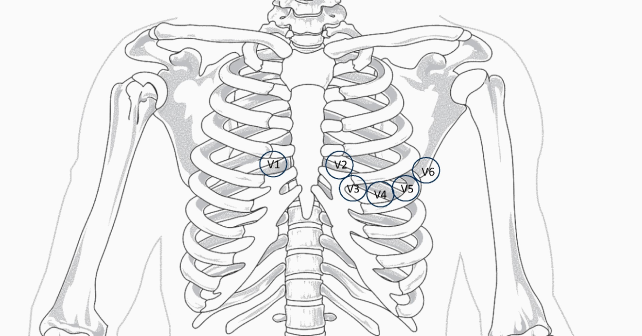

A repeat ECG (see figure 3) was performed utilizing the technique described by Sangwatanaroj et al., with right precordial lead modification, moving lead V3 one intercostal space above V1 and V4 one space above V2 (third intercostal space).1,2 This ECG showed Brugada pattern with coved ST-segment and J point elevation in V1 and V2.

Figure 3: An ECG obtained with modified “high” lead placement confirming Brugada syndrome. (Click to enlarge.)

Pediatric cardiology was consulted. His ECG demonstrated normal biventricular systolic function, mildly elevated pulmonary pressures, and a structurally normal heart. He underwent placement of a dual chamber, implantable, cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) placement on hospital day 5. At discharge, his neurological insult was severe, with significantly impaired physical and cognitive function, aspiration of feeds, and visual impairment.

Discussion

Brugada syndrome is an inherited disorder, due to a sodium channelopathy, characterized by right ventricular conduction delay, “coved” ST-segment elevation in the right precordial leads (V1-V3), and an increased risk of syncope and sudden cardiac death.3-6 Additional features include first-degree atrioventricular block, atrial arrhythmias, nocturnal agonal breathing, and seizures. Arrythmias are common during febrile illnesses and in sleep.

Figures 4:

A. Type 1 is diagnostic and characterized by J point and ST elevation > 2 mV with coved ST- elevation in at least two precordial leads, followed by negative T wave.

B. Type 2 is characterized by elevated J point and elevated ST ≥ 1 mm, saddle-shaped, flat and followed by positive T wave.

C. Type 3 is indicated by J point and ST elevation < 1 mm.

(Click to enlarge.)

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

No Responses to “Case Report: Cardiac Arrest in a Child’s Structurally Normal Heart”