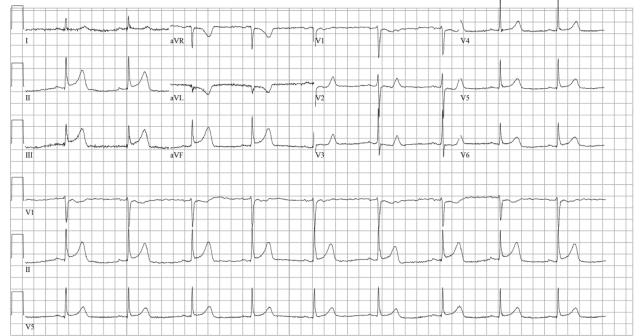

A 45-year-old male with a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, amphetamine and tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) use, and coronary vasospasm presented to triage with chest pain. During initial assessment, an ECG was obtained and revealed ST-segment elevation (STE) in the inferior leads with ST depression anteriorly.

Explore This Issue

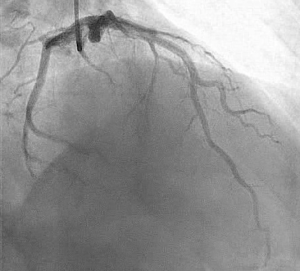

ACEP Now: Vol 43 – No 12 – December 2024During assessment, the patient reported that a left heart catheterization six months prior indicated “spasms” but no coronary artery disease. Before nitroglycerin (NTG) could be administered, the patient became unresponsive and was transferred to the resuscitation bay, where the monitor revealed a ventricular fibrillation arrest. Advanced cardiac life support protocol was initiated, and the patient was intubated. During this time, a comprehensive chart review was conducted that revealed the patient had experienced two prior ventricular fibrillation arrests, both resolved with intracoronary NTG during left heart catheterization, showing severe dominant circumflex spasm resulting in 99 percent occlusion, which abated with intracoronary NTG.

The patient was deemed to be in refractory fibrillation.

What Would You Do Next?

Attention was turned to the consideration of severe coronary vasospasm as the inciting event for cardiopulmonary arrest and the nidus for refractory ventricular fibrillation. The decision was made to communicate directly with the on-call interventional cardiologist with specific and direct intent to discuss the administration of intravenous (IV) NTG.

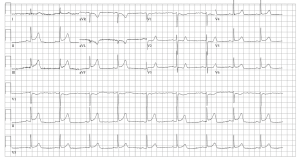

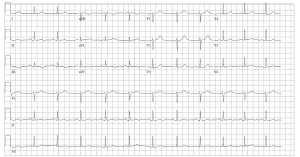

After the fourth defibrillation attempt, 200 mcg IV NTG was administered, resulting in immediate return of spontaneous circulation with a junctional bradycardia rhythm. Several minutes later, the patient again lost pulses, this time with pulseless electrical activity. After resuming CPR and administering an additional 400 mcg IV NTG, the patient achieved return of spontaneous circulation with sinus tachycardia. A repeat ECG was simultaneously performed that showed complete resolution of prior inferior elevation and anterior depression.

The patient was admitted to the cardiovascular intensive care unit and extubated the same day, neurologically intact. An urgent left heart catheterization revealed diffuse mild coronary atherosclerosis with normal ejection fraction. He was transferred out of the intensive care unit the next day and discharged shortly after, neurologically intact and at baseline.

Discussion

Since Prinzmetal and colleagues first described patients with coronary vasospasm as “variant angina” in 1959, the close relationship between this disorder and cardiac arrest has often been noted.1 Relatively little literature on the clinical characteristics and outcomes of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) patients complicated by coronary vasospasm exists beyond anecdotal reports, however. Overall, cardiac arrest in the setting of coronary vasospasm is thought to be relatively uncommon.2 OHCA patients with coronary vasospasm are typically younger, predominantly male, and often present with ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia as the initial rhythm. Traditional Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support (ACLS) medications, namely epinephrine, have been known to exacerbate coronary vasospasm.3 NTG is a potent coronary arterial dilator and is routinely used for ischemic discomfort in the setting of acute coronary syndrome, but is not typically deployed in the management of cardiac arrest. This case report documents the first known instance of using NTG during an emergency department resuscitation to treat a patient in cardiac arrest due to severe coronary artery vasospasm.

Cardiac arrest secondary to myocardial ischemia from coronary vasospasm is well documented. The ECG showed ST-segment elevation without obstructive coronary disease. Coronary vasospasm is linked to either hyperreactivity or vasoconstrictor stimuli on vascular smooth muscle cells. Vasodilators, like nitrates and calcium channel antagonists, are standard treatments.4

Amphetamines are central nervous system stimulants that release catecholamines, creating a hyperadrenergic state.5 Developed more than 100 years ago, its illicit use has surged in the last 25 years. Methamphetamine can cause severe cardiovascular effects, including elevated blood pressure, vasospasm, and atherosclerotic disease. The mechanisms in methamphetamine users are not well understood. Acute exposure promotes vasoconstriction and cerebral hypoperfusion due to neurovascular damage and imbalance of vasoregulatory substances.6 Vascular tone and blood pressure are regulated by neuronal stimulation and endothelial-derived substances.7 Endothelin, angiotensin II, and catecholamines cause vasoconstriction via G protein-coupled receptors, whereas vasodilators like nitric oxide reduce contraction by inhibiting calcium influx or myosin phosphorylation. Methamphetamine-induced vasoconstriction involves endothelial release of endothelin-1 or arterial TAAR1 signaling. Methamphetamine use is often associated with acute angina and coronary vasospasm, reducing blood flow to cardiac tissue.

We present a case of refractory ventricular fibrillation resuscitation due to coronary vasospasm from recent amphetamine use with IV NTG. No existing algorithm or literature guides the validity of a NTG strategy for vasospastic cardiac arrest in the emergency department. We hypothesize that OHCA in younger patients could often be attributed to coronary vasospasm and that traditional ACLS strategies may exacerbate the condition. Further studies are needed to develop safe resuscitation strategies for these patients.

Dr. Godwin is a recent graduate from the Kennestone Emergency Medicine Residency Program and currently works as an emergency physician at Atrium Health Floyd in Rome, Ga.

Dr. Godwin is a recent graduate from the Kennestone Emergency Medicine Residency Program and currently works as an emergency physician at Atrium Health Floyd in Rome, Ga.

Dr. Accilian is an emergency physician at Wellstar Kennestone Regional Medical Center, Marietta, Ga.

Dr. Accilian is an emergency physician at Wellstar Kennestone Regional Medical Center, Marietta, Ga.

Dr. Rad is ED faculty at Wellstar Kennestone Regional Medical Center in Marietta, Ga., and at Naples Community Hospital in Naples, Fla.

Dr. Rad is ED faculty at Wellstar Kennestone Regional Medical Center in Marietta, Ga., and at Naples Community Hospital in Naples, Fla.

References

- Prinzmetal M, Kennamer R, Merliss R, et al. Angina pectoris. I. A variant form of angina pectoris; preliminary report. Am J Med. 1959;27:375-388.

- Myerburg RJ, Kessler KM, Mallon SM et al. Life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias in patients with silent myocardial ischemia due to coronary-artery spasm. N Engl J Med. 1992;326(22):1451-1455.

- Magid DJ, Aziz K, Cheng A, et al. Part 2: evidence evaluation and guidelines development: 2020 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2020;142(16 suppl_2):S358–S365.

- Lanza GA, Careri G, Crea F. Mechanisms of coronary artery spasm. Circulation. 2011;124(16):1774-1782.

- Yamamoto BK, Moszczynska A, Gudelsky GA. Amphetamine toxicities: classical and emerging mechanisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1187:101-121.

- Kousik SM, Graves SM, Napier TC, et al. Methamphetamine-induced vascular changes lead to striatal hypoxia and dopamine reduction. Neuroreport. 2011;22(17):923-928.

- Loh YC, Tan CS, Ch’ng YS, et al. Overview of the microenvironment of vasculature in vascular tone regulation. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(1):120.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Case Report: Coronary Vasospasm-Induced Cardiac Arrest”