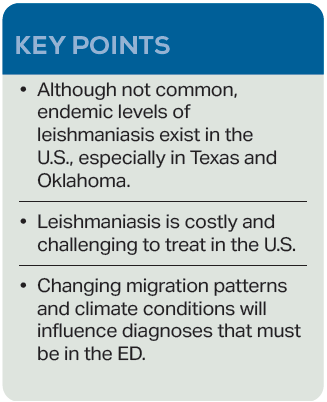

Conventional treatment for CL involves local topical treatment or systemic treatments. There is one parenteral treatment approved, amphotericin B, which is highly toxic and generally reserved for severe cases of diffuse disease or visceral leishmaniasis. There is one oral treatment that is FDA approved, miltefosine 50 mg three times daily for 28 days. A full course of this medication costs approximately $60,000. There are topical medications, paromomycin and pentavalent antimonial (SbV) compounds, available in other countries, but none has been approved by the FDA.5 It is possible, although challenging, to get these medications through compounding pharmacies in the U.S.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 43 – No 02 – February 2024Discussion

As the refugee crisis continues, and asylum seekers visit emergency departments all over the U.S., physicians will be exposed to pathologies we may have only heard about in medical school. Climate change will also influence the prevalence of CL and other conditions traditionally considered tropical diseases. This is from a combination of human migration patterns and the expansion of climate conditions in which the sand fly vectors can survive.6 Currently, climate models estimate that 12 million people live in locations in which leishmaniasis is endemic in the U.S. Because of no required tracking or reporting, we have no accurate measure.7 This case emphasizes the importance of maintaining a wide differential, especially when evaluating asylum seekers who have been exposed to a wide variety of environments and pathogens. Our local infectious disease specialist estimates that the last time a case of CL was seen at this hospital was at least 15 to 20 years ago.

Dr. Englof is current faculty of the Swedish Hospital Emergency Medicine Residency (part of Endeavor Health) in Chicago, and a program coordinator for EMGLEX, an immersive emergency medicine rotation for international physicians.

Dr. Englof is current faculty of the Swedish Hospital Emergency Medicine Residency (part of Endeavor Health) in Chicago, and a program coordinator for EMGLEX, an immersive emergency medicine rotation for international physicians.

Dr. Dupont is a second-year emergency medicine resident at Swedish Hospital in Chicago.

Dr. Dupont is a second-year emergency medicine resident at Swedish Hospital in Chicago.

References

- Ruiz-Postigo JA, Jain S, Madjou S, et al. Global leishmaniasis surveillance: 2021, assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Weekly Epidemiological Record. 2022;97(45):575-590.

- Curtin JM, Aronson NE. Leishmaniasis in the United States: Emerging issues in a region of low endemicity. Microorganisms. 2021;9(3):578.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Leishmaniasis – Epidemiology & risk factors. CDC website. Last reviewed February 18, 2020. Accessed January 15, 2024.

- Convit J, Ulrich M, Fernàndez CT, et al. The clinical and immunological spectrum of American cutaneous leishmaniasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1993;87(4):444-448.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Leishmaniasis – Resources for Health Professionals. CDC website. Last reviewed October 5, 2023. Accessed January 15, 2024.

- World Health Organization. Leishmaniasis. WHO website. Published January 12, 2023. Accessed January 15, 2024.

- Barnhart, M. A ‘tropical disease’ carried by sand flies is confirmed in a new country: the U.S. National Public Radio website. Published November 1, 2023. Accessed January 15, 2024.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

No Responses to “Case Report: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Chicago”