A 29-year-old Hispanic American man with no significant medical history presented to the emergency department (ED) with a progressively worsening respiratory and systemic illness. His symptoms had begun two weeks prior, initially as a mild cough, congestion, and shortness of breath. About one week later, he started experiencing generalized body aches, nausea, and vomiting. By the day before his ED visit, his symptoms had worsened, and he developed new onset chills and muscle pain, which prompted him to seek care. He reported no recent travel outside of the country and no occupational or recreational exposures to arthropods or small mammals.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 44 – No 02 – February 2025On arrival, he appeared diaphoretic and was in visible respiratory distress, with labored breathing and signs of acute discomfort. His physical examination revealed a punctate macular rash on his lower extremities and posterior thorax, which was initially thought to be nonspecific (see image 1). Given his significant distress, a comprehensive workup was initiated to rule out possible infectious, hematologic, and respiratory conditions.

A complete blood count (CBC), basic metabolic panel, hepatic function panel, urinalysis, respiratory viral panel, blood smear, ferritin, procalcitonin, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, blood cultures, and imaging studies were ordered. Imaging included a chest X-ray, CT angiogram (CTA) of the chest, and a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis. Initial lab results revealed hyponatremia with a sodium of 130 mmol/L, and aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase of 192, 140. His ferritin level was markedly elevated at 3,371.8 ng/mL, and his procalcitonin level was significantly increased at 6.84 ng/mL, both suggestive of a systemic inflammatory response. His CBC showed a low platelet count of 20,000/µL, mild anemia with a hemoglobin level of 12.1 g/dL, and a white blood cell count of 6.85 thousand/µL with a neutrophil predominance (92 percent) and the presence of smudge cells and schistocytes.

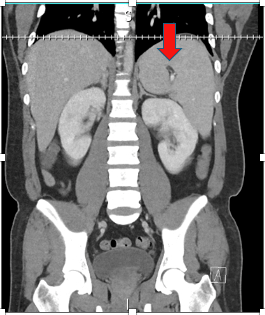

Image 3: CT abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast showing splenomegaly and splenic infarct. (Click to enlarge.)

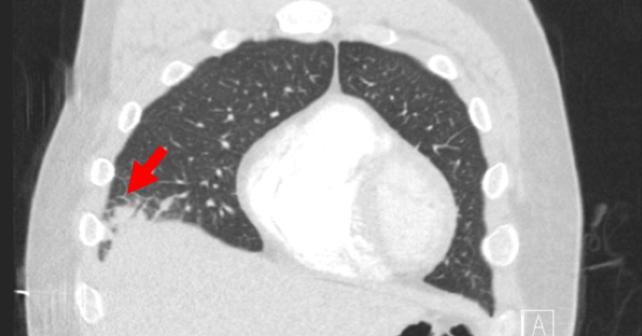

Chest CTA showed no evidence of pulmonary embolism; notable abnormalities included a right middle lobe consolidation consistent with pneumonia (see image 2), left ventricular dilation, interstitial pulmonary edema, and enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes. Abdominal CT revealed splenomegaly along with a splenic infarct (image 3). These findings collectively suggested a systemic inflammatory or infectious process with potential multiorgan involvement, but the specific cause remained unclear at this stage.

Given the clinical picture, the initial differential diagnosis included sepsis, bacterial or viral pneumonia, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, pulmonary embolism, and acute coronary syndrome.

Broad spectrum antibiotics were promptly initiated to cover community-acquired pneumonia, with the patient initially receiving ceftriaxone and azithromycin. His fever and systemic symptoms persisted despite this regimen; antibiotics were escalated to vancomycin and cefepime. Even with the change in therapy, the patient continued to exhibit febrile episodes, and his respiratory and systemic symptoms showed no improvement.

On the seventh day of hospitalization, clinicians revisited the possibility of an unusual infectious etiology. Given the epidemiologic context and high clinical suspicion, murine typhus was considered as a possible diagnosis. The patient resided in Southeast Texas, an endemic area for murine typhus, a zoonotic disease transmitted through fleas often associated with rodents.1 Although no clear risk factors were identified, the clinical team started doxycycline empirically, given the lack of response to previous therapies and the constellation of findings, including thrombocytopenia, splenomegaly, elevated liver enzymes, and a characteristic rash.

Subsequently, serological testing confirmed the diagnosis, with positive immunoglobulin M titers for murine typhus. After initiating doxycycline, the patient’s clinical condition began to significantly improve. His fever resolved, his respiratory symptoms diminished, and his general condition stabilized. By day 14, he was well enough to be discharged in stable condition, with instructions to complete his course of doxycycline at home.

Discussion

Murine typhus, a disease transmitted by fleas, is caused by the intracellular bacterium Rickettsia typhi.1 Characterized by a range of nonspecific symptoms, including fever, myalgia, and rash, murine typhus often presents a diagnostic challenge that can be elucidated through a careful exposure and travel history. Most cases diagnosed in the United States have been identified in California, Hawaii, and Texas, although returning travelers from Southeast Asia are also at higher risk.2-4T his report discusses a case of murine typhus that initially presented as severe pneumonia and sepsis and illustrates the importance of timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

This case highlights the importance of considering murine typhus in patients presenting with respiratory symptoms, thrombocytopenia, and systemic signs of infection. Risk for typhus is especially high among patients with recent exposures to mice or fleas, or travel to endemic areas like Southeast Texas; however, most cases cannot identify discrete exposures.5 The clinical presentation of murine typhus can overlap with that of common bacterial and viral pneumonias, as well as with conditions like sepsis and DIC, potentially leading to misdiagnosis if it is not part of the differential.4 In cases where standard treatments for respiratory infections fail, reevaluation of the diagnosis and consideration of regional epidemiologic factors are essential.6

In conclusion, this case underscores the need for heightened awareness of zoonotic infections such as murine typhus, particularly in emergency and critical care settings where delayed recognition can adversely affect outcomes.

Dr. Johnson is PGY-2 in emergency medicine at University of Texas at Houston Medical Center.

Dr. Johnson is PGY-2 in emergency medicine at University of Texas at Houston Medical Center.

Dr. Dyal is an assistant professor of emergency medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Dr. Dyal is an assistant professor of emergency medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

References

- Lonergan S, Ganesan G, Titus SJ, et al. Murine typhus. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2022;35(5):663-664.

- Tsioutis C, Zafeiri M, Avramopoulos A, et al. Clinical and laboratory characteristics, epidemiology, and outcomes of murine typhus: a systematic review. Acta Trop. 2017;166:16-24.

- Azad AF. Epidemiology of murine typhus. Annu Rev Entomol. 1990;35:553-569.

4. Lara GP, Dzul-Rosado KR, Velázquez JEZ, et al. Murine typhus: clinical and epidemiological aspects. Colomb Méd (Cali). 2012;43(2):175-180.

- Znazen A, Hammami B, Mustapha AB, et al. Murine typhus in Tunisia: a neglected cause of fever as a single symptom. Med Mal Infect. 2013;43(6):226-229.

- Salomon J, Leeke E, Montemayor H, et al. On-host flea phenology and flea-borne pathogen surveillance among mammalian wildlife of the pineywoods of East Texas. J Vector Ecol. 2024;49(2):R39-R49.

- Salje J, Weitzel T, Newton PN, et al. Rickettsial infections: A blind spot in our view of neglected tropical diseases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15(5):e0009353.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Case Report: Murine Typhus Presents as Severe Pneumonia and Sepsis”