Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks are rare. But when seen in an emergency department, they should be recognized as part of a potentially life-threatening process. Emergency physicians mostly encounter CSF leaks in the setting of traumatic injuries, but they can also occur in atraumatic settings. CSF leaks have potential implications for serious intracerebral infection, pain, and, if left untreated, significant morbidity and mortality. Here, we discuss a case of a persistent atraumatic CSF leak in an otherwise healthy young woman.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 39 – No 08 – August 2020The Case

A mid-40s woman presented to the emergency department from home following three weeks of a persistently runny nose. She recently had an upper respiratory infection, but on arrival was symptom-free with the exception of rhinorrhea. She had the “sniffles” for several days three weeks ago but had been feeling fine since. However, her nose has been “constantly” running, requiring that she pack her nose with tissue just to complete her daily activities. No traumatic injury was reported. The patient reported a mild headache that worsened with sitting or standing up after lying flat. She had no signs or symptoms of an ongoing active infection at the time of presentation and showed no meningeal signs. On exam, she was noted to have persistent, clear, continuous drainage from the right nostril. This was markedly pronounced

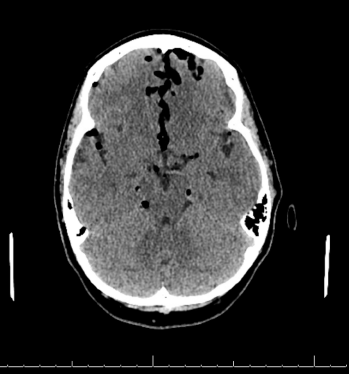

Figures 1 (ABOVE) and 2 (BELOW): CT scan with large-volume atraumatic pneumocephalus.

when she would lean forward. pH paper was brought to bedside and, with application of the patient’s nasal drainage, demonstrated a “halo” sign and pH measuring near 7.0. These findings were consistent with a suspected CSF leak. CT scan of the head demonstrated significant pneumocephalus (see Figures 1 and 2). She was found to have erosion of the right posterior maxillary sinus. She underwent fat grafting from the abdomen to repair the sinus defect the next day. After repair, she recovered well with no complications.

Discussion

Pneumocephalus is pathologic air in the intracranial cavity. Air may be located in the epidural, subarachnoid, intraventricular, intracerebral, and, most commonly, subdural space. Pneumocephalus may arise through two different mechanisms: 1) a “ball valve” mechanism where air enters through a defect in the dura and is unable to exit due to overlying tissue, or 2) an “inverted soda bottle” mechanism where a CSF leak generates negative intracranial pressure, allowing air to replace lost CSF. Trauma accounts for nearly 75 percent of cases.1,2 Small volumes of air (less than 1–2 mL) are common following head trauma, and pneumocephalus can also be seen with fractures of the skull base that breach the dura, penetrating head trauma with dural lacerations, and fractures of the air-filled sinuses. Nontraumatic etiologies include infection with gas-producing organisms such as in meningitis or chronic sinusitis or otitis media; eroding tumors of the skull base; and iatrogenic causes including cranial, spinal, or ENT surgery.3 Pneumocephalus and CSF leaks may also occur spontaneously or secondary to congenital defects.4

Pneumocephalus is pathologic air in the intracranial cavity. Air may be located in the epidural, subarachnoid, intraventricular, intracerebral, and, most commonly, subdural space. Pneumocephalus may arise through two different mechanisms: 1) a “ball valve” mechanism where air enters through a defect in the dura and is unable to exit due to overlying tissue, or 2) an “inverted soda bottle” mechanism where a CSF leak generates negative intracranial pressure, allowing air to replace lost CSF. Trauma accounts for nearly 75 percent of cases.1,2 Small volumes of air (less than 1–2 mL) are common following head trauma, and pneumocephalus can also be seen with fractures of the skull base that breach the dura, penetrating head trauma with dural lacerations, and fractures of the air-filled sinuses. Nontraumatic etiologies include infection with gas-producing organisms such as in meningitis or chronic sinusitis or otitis media; eroding tumors of the skull base; and iatrogenic causes including cranial, spinal, or ENT surgery.3 Pneumocephalus and CSF leaks may also occur spontaneously or secondary to congenital defects.4

Patients typically present with headaches that are worsened by Valsalva maneuvers or leaning forward and improved by lying supine.4 There may be associated neck pain and stiffness, nausea, vomiting, irritability, or dizziness. However, patients may also be asymptomatic. CT scan is the gold standard for identifying the presence of air in the cranial vault and can detect air volumes as small as 0.55 mL. Larger volumes of air can compress the frontal lobes and widen the interhemispheric space, creating the characteristic Mount Fuji sign.1 Plain films can also be used but may miss small volumes of air. MRI is less sensitive than CT for identifying pneumocephalus, although it is best for identifying the source of a CSF leak. MRI may demonstrate subdural fluid collection, meningeal enhancement, venous congestion, pituitary swelling, and inferior displacement of the cerebellar tonsils.4

A small pneumocephalus may be managed conservatively, as intracranial air will reabsorb. Reabsorption can be aided with high-flow supplemental oxygen delivered via face mask with the patient on bed rest in the Fowler (semi-seated) position at 30 degrees.3 Patients should also be instructed to avoid Valsalva maneuvers such as coughing or sneezing, as this may reopen the dural defect. Hyperbaric oxygenation therapy may also be considered for treatment of small pneumocephalus. Be careful to avoid larger volumes of air, as this can result in intracranial hypertension, known as tension pneumocephalus. The ensuing mass effect may cause significant neurological decline and herniation requiring surgical intervention. Surgery may also be required to repair culprit dural defects or for emergent decompression of tension pneumocephalus. Some patients may benefit from blood patch placement for symptom relief.4

Potential complications of pneumocephalus include meningitis, seizures owing to cerebral cortex irritation by air, brain abscesses, and brain herniation resulting from tension pneumocephalus.

Summary

During a busy shift, it is easy to just call a runny nose a runny nose. However, we have to stay alert for life-threatening pathologies for seemingly simple chief complaints, as early identification of such cases can reduce morbidity and associated complications. Nothing beats a thorough physical exam and history. Be aware of your own anchoring bias and identify it when you sense it affecting your care. Take the time and effort to get a clear and detailed history from the patient. And remember, not all clear fluid is good.

Ms. Hinton is a fourth-year medical student at University of Colorado School of Medicine in Aurura who is interested in emergency medicine.

Ms. Hinton is a fourth-year medical student at University of Colorado School of Medicine in Aurura who is interested in emergency medicine.

Dr. Trop is an attending physician in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

Dr. Trop is an attending physician in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

References

- Dabdoub C, Salas G, Silveira ED, et al. Review of the management of pneumocephalus. Surg Neuro Int. 2015;6:155.

- Vacca VM. Pneumocephalus assessment and management. Nurs Crit Care. 2017;12(4):24-29.

- Schirmer CM, Heilman CB, Bhardwaj A. Pneumocephalus: case illustrations and review. Neurocrit Care. 2010;13(1):152-158.

- Schievink WI. Spontaneous spinal cerebrospinal fluid leaks and intracranial hypotension. JAMA. 2006;295(19):2286-2296.

Pages: 1 2 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Case Report: Persistent Runny Nose Follows Upper Respiratory Infection”