At FQR rates of 10 to 20 percent, IDSA recommends a long-acting antibiotic of another class (eg, ceftriaxone or a single daily dose of an aminoglycoside) in addition to a fluoroquinolone. At FQR rates exceeding 20 percent, IDSA recommends abandoning fluoroquinolones, and this is where ESBLs come into play. Risk factors for ESBL infections were the same as for FQR. However, about one-third of patients with ESBL infections had no risk factors, indicating that ESBLs are now endemic in some US communities. This is becoming much like the situation seen in South America, India, Southeast Asia, and Southern Europe.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 35 – No 11 – November 2016Note, however, that high FQR rates and emerging ESBLs are not yet a problem everywhere in the United States—so watch for increasing FQR rates. Your lab may or may not indicate an isolate is an ESBL strain. However, if it reports resistance to ceftriaxone, you can assume the bacteria are ESBL producers.

(click for larger image)

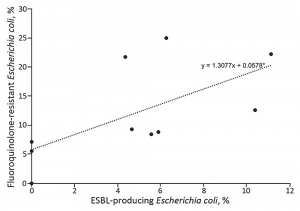

Figure 3. Prevalence of fluoroquinolone-resistant and ESBL-producing Escherichia coli infections among patients with uncomplicated and complicated pyelonephritis by study site, United States, July 2013–December 2014. Each dot indicates a study site; the line to show the general trend between fluoroquinolone resistance and ESBL-producing E. coli was generated by using simple linear regression.

Source: CDC.

Locations with high FQR rates also have high ESBL rates (see Figure 3), so emergency physicians now need to know reliable empirical treatments for this emerged pathogen. ESBLs are resistant to all commonly used cephalosporins (eg, ceftriaxone) and frequently resistant to both fluoroquinolones and gentamicin. ESBLs are nearly universally susceptible to carbapenems, including long-acting ertapenem. The majority but not all isolates are susceptible to piperacillin-tazobactam and amikacin. Some newer but less available agents (ceftazidime-avibactam and ceftolozane-tazobactam) are very active against ESBLs.

Choosing the Right Drugs

The real question is, when do I pull the ESBL antibiotic trigger? Here is what I think is the best answer:

In settings with high FQR rates (above 15 percent), where ESBL-producing E. coli infections have emerged, and among persons with antimicrobial drug resistance risk factors—and especially for patients with or at risk for severe sepsis—you should consider empirical treatment with a carbapenem or another agent found to be consistently active based on the local antibiogram. Checking a patient’s past infections and understanding local resistance rates are key. If you’re lucky enough to have an ED pharmacist, having them track and report current resistance rates should be a priority. (You can expect updated IDSA guidelines soon.)

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

No Responses to “Choosing Right Medication Critical to Combat Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase Infections”