The first gathering of what would become Illinois Unidos, a consortium dedicated to addressing the impact of COVID-19 in the Latino community, is still vivid in the mind of Marina Del Rios Rivera, MD, MSc. “It was a Saturday in April [2020], and I remember how somber that meeting was when we recognized the magnitude of what was about to happen in our community,” she said.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 40 – No 06 – June 2021An associate professor at the University of Illinois College of Medicine and an emergency medicine specialist at the university’s hospital, Dr. Del Rios Rivera was referring to not just the Chicago community that her hospital serves but also the disproportionately vulnerable Latino community in Illinois.

Born in Puerto Rico, the daughter of a father who worked a janitor and a mother whose education did not go beyond sixth grade, Dr. Del Rios Rivera acknowledges that as a physician, she has privilege—and she feels compelled to use it on behalf of those who do not. This has meant a decade of community service volunteer work in the Latino community for Dr. Del Rios Rivera—and in this instance, it felt especially important as Latino people in the United States are more likely to be infected with and die from COVID-19 than white people. Latino people also experience a disproportionate amount of COVID-related financial burdens, which may include work-hour reduction, unemployment, and inability to access government benefits due to citizenship status.

Illinois Unidos was born on that day last spring when a group of community leaders from around the state met to address these challenges. Dr. Del Rios Rivera became a founding member and is now chair of the health and policy committee. The organization has grown to about 100 members who actively participate in task forces that meet biweekly between their bigger plenary meetings. Thousands serve the group as affiliated members of independent community service organizations. These include the primarily Latino-serving federally qualified health centers located in areas that might otherwise be health care deserts as well as advocacy organizations like the Latino Policy Forum and the Puerto Rican Agenda. They also include representatives from academic health equity centers and the Great Cities Institute, which is part of University of Illinois at Chicago. And then there are members from work groups like Arise Chicago, which builds partnerships between faith communities and workers to fight workplace injustice through education, and Raise the Floor Alliance, which advocates for low-wage workers to achieve justice in Chicago. “Each of us have, in turn, another set of constituents that we respond to and advocate for,” she said.

Including Outreach in a Busy Schedule

Dr. Marina Del Rios Rivera

In addition to her other roles, Dr. Del Rios Rivera is director of Social Emergency Medicine at the university. Most of her research is on resuscitation related to cardiac arrest, specifically focused on community preparedness and teaching bystander CPR and the proper use of automated external defibrillators. Her research also examines how geography plays a role in survival so that she and her colleagues can focus their efforts on communities with the highest risk of death. Her involvement with Illinois Unidos, she said, is like another full-time job.

On top of that, she and her husband, a law professor now teaching from home, have two sons, 11 and 14, both doing hybrid schooling. While she used to do a lot of work from her office to minimize distractions, at the time of this interview she was trying to avoid the office as much as possible for infection control, so the family had to restructure their setup at home to ensure they each had adequate space to work.

“You do what you have to do,” she said. “This is inconvenient, but I think that I’m, again, very privileged in that I have this flexibility. I feel for the parents that physically have to go to work and are also juggling having to help their children with online learning and making sure that they’re safe.”

Dr. Del Rios Rivera still works overnight shifts in the emergency department—“Sleep? What’s sleep?” she said—and continues her cardiac arrest research, now looking at national data sets and doing predictive modeling to understand how some communities manage cardiac arrest well versus communities that do not. She also mentors medical students through the Hispanic Center of Excellence and the Urban Health Program, some of whom assist with her COVID-19-related community service work specifically for the Latino community, like helping put together information sheets, delivering messaging, and engaging with communities.

Building Awareness Powered by Data

Dr. Del Rios Rivera became involved with Illinois Unidos after community members began organizing to look at the COVID-19 data in a different way. Since the Latino community knows her, they reached out when it became clear in April that Latino people were not being included in the narrative of disparities and cardiac arrest.

“There seemed to be an absence of discussion of the crisis that was already occurring in our communities,” she said.

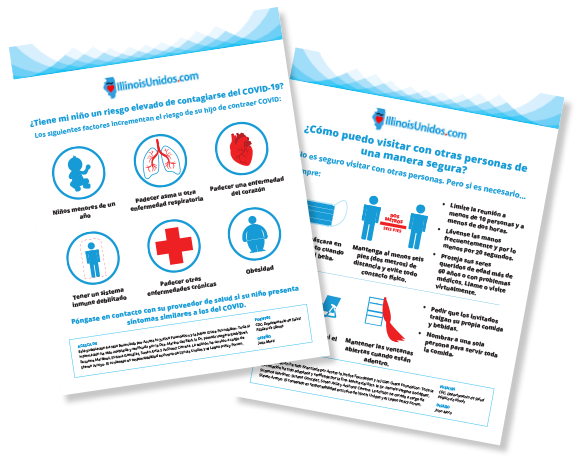

Illinois Unidos provides COVID-19 information sheets in Spanish and English on its website, IllinoisUnidos.com.

Illinois Unidos

At that point, the City of Chicago and the State of Illinois were mostly providing overall rates of COVID-19 illness, with a recognition that the Black population in the state was being disproportionately affected. In Latino communities, however, there was also a high rate of illness and mortality, but it was not yet being discussed. The community’s fear, she said, was that there was undercounting and underreporting related to the way the state and the city were looking at the data.

“We have some data-savvy people that are community members who started looking at COVID-19 rates by ZIP code, and there was a recognition that there were predominantly Latino ZIP codes that had high rates of infection and high rates of mortality,” she said. She thought the first meeting of Illinois Unidos would be like a think tank to discuss what to do next. But it grew into weekly meetings to discuss ongoing issues like how to garner media attention, gather resources, and have conversations with Latino government officials in the state and City of Chicago.

“From that, we’ve learned we all have different expertise, and different leadership roles have arisen throughout the time of the pandemic,” she said.

The coalition has focused not only on getting bilingual and bicultural information on COVID-19 into the Latino community but also providing testing and personal protective equipment and advocating for resources to take care of COVID-19 survivors and their families, some of whom are of mixed status and include undocumented people who don’t typically qualify for resources.

Beyond COVID-19, Dr. Del Rios Rivera said the Latino community confronts problems of structural racism similar to those faced by Black and Native American communities, including redlining, food/pharmacy/health and hospital deserts, and people being left out of worker protections due to discrimination. “The additional piece with the Latino community, though, is the language component,” she said, “and the fact that many are not citizens, so they are treated worse because there’s no protections in place for people that don’t have the U.S. citizen badge.”

The silver lining, she said, is that the pandemic shined a light on existing problems and issues with infrastructure that needed to be fixed anyway. She is hoping the same model can be used not just for another possible pandemic but also to point to hot spots in all communities to improve conditions like heart disease, asthma, and diabetes. “I know that sometimes the community reaches out to us for expertise, but I actually find that I’ve learned a lot in this process,” Dr. Del Rios Rivera said. “I am certainly not an expert in community affairs, so a lot of this has been listening so you can be a voice to speak alongside other people rather than imposing your thoughts and beliefs on the community.”

Renée Bacher is a freelance medical writer located Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Combating COVID in Latino Communities”