It used to be said that missing the clinical diagnosis of aortic dissection was “the standard” as it is rare and often presents atypically. The diagnosis rate of aortic dissection changed with the landmark International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD) study in 2000, which deepened our understanding of the presentation.1 Nonetheless, aortic dissection remains difficult to diagnose, with one in six missed at the initial ED visit.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 36 – No 11 – November 2017Herein lies the difficulty. Aortic dissection must be considered in all patients with chest, abdominal, or back pain; syncope; or stroke symptoms. Yet, we shouldn’t be working up every one of them, creating a resource utilization disaster. However, early, timely diagnosis is essential because each hour that passes from the onset of symptoms correlates with a 1 percent to 2 percent increase in mortality.

In this column, I’ll elucidate how to improve your diagnosis rate, without overimaging, by explaining five pain pearls, the concepts of “CP +1” and “1+ CP,” physical exam nuances, and how best to initially utilize tests.

The Five Pain Pearls of Aortic Dissection

- Ask the following three things of all patients with torso pain:

- What is the quality of pain? (The pain from aortic dissection is most commonly described as “sharp,” but the highest positive likelihood ratio [+LR] is for “tearing.”)

- What was the pain intensity at onset? (It is abrupt in aortic dissection.)

- What is the radiation of pain? (It is in the back and/or abdomen in aortic dissection.)

A 1998 study that reviewed a series of aortic dissection cases showed that for the 42 percent of physicians who asked about these three things, the diagnosis was suspected in 91 percent. When fewer than three questions were asked, dissection was suspected in only 49 percent.2

- Think of aortic dissection as the subarachnoid hemorrhage of the torso. Just like a patient who presents with a new-onset, severe, abrupt headache should be suspected of having a subarachnoid hemorrhage, if a patient describes a truly abrupt onset of severe torso pain with maximal intensity at onset, think aortic dissection.

- If you find yourself treating your chest pain patient with IV opioids to control severe colicky pain, think about aortic dissection.

- Migrating pain has a +LR of 7.6.1 In addition to the old adage, “Pain above and below the diaphragm should heighten your suspicion for aortic dissection,” severe pain that progresses and moves in the same vector as the aorta significantly increases the likelihood of aortic dissection.

- The pain can be intermittent as dissection of the aortic intima stops and starts. The combination of severe migrating and intermittent pain should raise the suspicion for aortic dissection.

Painless Aortic Dissection

While IRAD reported a painless aortic dissection rate of about 5 percent, a more recent study out of Japan reported that 17 percent of aortic dissection patients had no pain.3 These patients presented more frequently with a persistent disturbance of consciousness, syncope, or a focal neurological deficit. Cardiac tamponade was more frequent in the pain-free group as well.

The Concepts of “CP +1” and “1+ CP”

The intimal tear in the aorta can devascularize any organ from head to toe, including the brain, heart, kidneys, and spinal cord. Thus, 5 percent of dissections present as strokes, and these certainly are not the kind of stroke patients who should be receiving tPA! An objective focal neurologic deficit in the setting of acute, unexplained chest pain (CP) has +LR of 33 for aortic dissection, almost diagnostic. Some of the CP +1 phenomena to think about include torso pain, cerebrovascular accident, paralysis, hoarseness (recurrent laryngeal nerve), and limb ischemia.

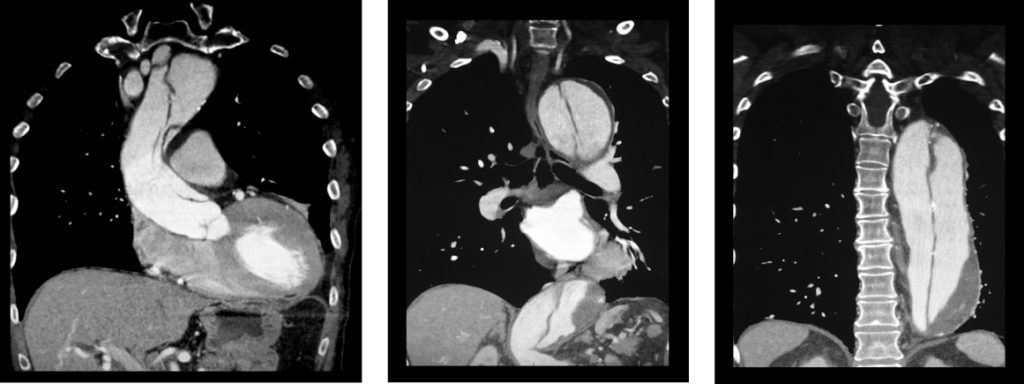

(click for larger image) These three coronal reconstructions from contrast enhanced CT angiograms of the chest show an extensive dissection of the thoracic aorta. This is a De Bakey type I or Standord A aortic dissection.

Source: Living Art Enterprises / Science Source

In addition to thinking of CP +1, it may help to think backwards in time (1+ CP) and ask patients who present with end-organ damage if they had torso pain prior to their symptoms of end organ damage. For example, ask patients who present with stroke symptoms if they had torso pain before the stroke symptoms.

Anyone under the age of 40 years who presents to the emergency department with unexplained torso pain should be asked if they have Marfan syndrome. In the IRAD analysis of those under 40 years, 50 percent of the aortic dissection patients had Marfan syndrome, representing 5 percent of all dissections.1

- Look. The patient doesn’t always know they have Marfan syndrome, so you need to look for arachnodactyly (elongated fingers), pectus excavatum (sternal excavation), and lanky limbs.

- Listen. A new aortic regurgitation murmur has a surprisingly high +LR of 5.

- Feel. Feel for a pulse deficit, which has a +LR of 2.7, much higher than that of interarm blood pressure differences.

The patient’s blood pressure needs to be interpreted with caution and insight. Do not assume that the patient with a normal or low blood pressure does not have an aortic dissection. We know from the IRAD data that only about half of patients are hypertensive at initial presentation. Patients with aortic dissections that progress into the pericardium, resulting in cardiac tamponade, are often hypotensive. Patients with dissection who have a wide pulse pressure should be considered preterminal and usually require immediate surgery.

There is a lot more to chest radiograph interpretation for suspected aortic dissection than looking for a wide mediastinum. One-third of chest radiographs in aortic dissection are normal to the untrained eye, and a common pitfall is to assume that if the chest X-ray is normal, the patient does not have an aortic dissection. There are about a dozen X-ray findings associated with dissection, but two of them are especially important: loss of the aortic knob/aortopulmonary window and the calcium sign.

Look for a white line of calcium within the aortic knob, then measure the distance from there to the outer edge of the aortic knob. A distance >0.5 cm is considered a positive calcium sign, and a distance >1.0 cm is considered highly suspicious for aortic dissection. It is always wise to compare to an old film to see if there’s been an interval change.

Eighteen percent of patients with aortic dissection will have a positive troponin test, so if you suspect the diagnosis based on other clinical findings, don’t assume isolated acute coronary syndrome when the troponin comes back positive.5 Remember that fewer than one in 100 patients with a dissection will have associated coronary ischemia in any coronary distribution (most commonly inferior).

While D-dimer seems like it might be appealing to help rule out the diagnosis in low-risk patients, for such a rare diagnosis and poor test characteristics of D-dimer for dissection, guidelines do not recommend the use of D-dimer for the workup of aortic dissection.6

Aortic dissection can be considered the retinal detachment of the torso. While the sensitivity of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) by emergency physicians to detect an intimal flap is only 67 percent, the specificity has been shown to be 99 percent to 100 percent.7 For patients suspected of the diagnosis, look for an intimal flap that looks similar to a retinal detachment on POCUS and look for a pericardial effusion indicative of a retrograde dissection into the pericardium.8

Take-Home Points

- Remember the big pain pearls when taking a history:

- Ask the three important questions.

- Aortic dissection should be considered the subarachnoid hemorrhage of the torso.

- Migrating pain, colicky pain, plus need for IV opioids should raise your suspicion.

- Intermittent pain can still be a dissection.

- Look for Marfan syndrome, listen for an aortic regurgitation murmur, and feel for a pulse deficit.

- Think not only about CP +1 but also 1+ CP.

- Know the radiographic findings of loss or aortic knob/aortopulmonary window and the calcium sign, and use POCUS to look for an intimal flap and pericardial effusion.

- Don’t be misled by a troponin or D-dimer.

Thanks to David Carr for his expert contributions to the EM Cases podcast that inspired this article.

References

- Hagan PG, Nienaber CA, Isselbacher EM, et al. The International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD): new insights into an old disease. JAMA. 2000;283(7):897-903.

- Rosman HS, Patel S, Borzak S, et al. Quality of history taking in patients with aortic dissection. Chest. 1998;114(3):793-795.

- Imamura H, Sekiguchi Y, Iwashita T, et al. Painless acute aortic dissection: diagnostic, prognostic and clinical implications. Circ J. 2011;75(1):59-66.

- Singer AJ, Hollander JE. Blood pressure: assessment of interarm differences. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(17):2005-2008.

- Leitman IM, Suzuki K, Wengrofsky AJ, et al. Early recognition of acute thoracic aortic dissection and aneurysm. World J Emerg Surg. 2013;8(1):47.

- Diercks DB, Promes SB, Schuur JD, et al. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients with suspected acute nontraumatic thoracic aortic dissection. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65(1):32-42.

- Sobczyk D, Nycz K. Feasibility and accuracy of bedside transthoracic echocardiography in diagnosis of acute proximal aortic dissection. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2015;13:15.

- Fojtik JP, Constantino TG, Dean AJ. The diagnosis of aortic dissection by emergency medicine ultrasound. J Emerg Med. 2007;32(2):191-96.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

One Response to “How to Diagnose Aortic Dissection Without Breaking the Bank”

November 26, 2017

EricVery well written article on dissection. I especially like the thought process of thinking of it as the subarachnoid hemorrhage of the torso- really helps to remember those 3 questions.