Bounceback visits provide an opportunity for emergency physicians to review a case again with a clear mind and fresh eyes. A renewed search for red flags in a patient’s presentation can help avoid a bad medical and legal outcome.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 40 – No 06 – June 2021The Case

A 47-year-old woman underwent a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. There were no immediate complications, and she had an uneventful course initially. Fifteen days later, she started to experience mild abdominal pain that worsened over the following two days.

She went to see a nurse practitioner (NP) at a local primary care office. The NP treated her with ceftriaxone and promethazine. The patient was instructed to immediately go to a nearby emergency department for evaluation. The emergency department was not affiliated with the hospital where she had the gastric bypass.

In the emergency department, she was evaluated by a physician. Her vitals showed a heart rate of 114 bpm, blood pressure of 141/74, 100 percent on ambient air, 28/min respirations, and temperature of 100.3° F. The note described left-sided abdominal pain with erythema and purulent fluid leaking from the incision site. There was extensive bruising on the left side of the abdomen. A postoperative drain was still in place.

Labs and CT of the abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast were ordered. She was treated with morphine, ondansetron, and a 1-L normal saline bolus.

Lab results were notable for a leukocytosis of 15.9 k/uL with neutrophilic predominance (70.9 percent). She was slightly hypokalemic at 3.2 mmol/L.

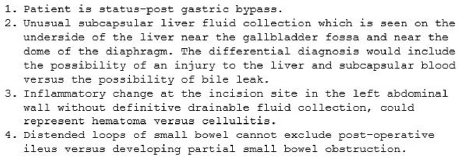

The CT scan results are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Patient’s CT scan results.

The patient’s heart rate improved to 89 bpm. Her blood pressure remained stable, and her pain improved from 9/10 to 4/10.

The emergency physician then contacted the hospital where the gastric bypass had been performed. He was able to reach the surgeon who performed the operation. They reviewed the entirety of her results. The surgeon recommended that the emergency physician perform a bedside drainage of the infection at the incision site. The surgeon also said he would see her in the clinic in the next few days for reassessment. She was given prescriptions for sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim and oxycodone.

The patient was discharged from the emergency department around 6 p.m.

About two hours later, the patient called 911 and returned to the emergency department for worsening abdominal pain. Her vitals at ED triage showed a heart rate of 132 bpm, blood pressure 131/72, 100 percent on ambient air, and a respiration rate of 37/min.

A new emergency physician saw the patient. He reviewed the previous notes and documented “CT scan earlier was fine.” It was noted that she had not yet filled the antibiotic prescription from the earlier visit.

The patient was treated with IV hydromorphone, oral sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, and oral oxycodone.

No further labs or imaging were ordered. The surgeon was not contacted again.

The patient’s heart rate climbed to 142 bpm.

The emergency physician then discharged her with instructions to fill her prescriptions and remain NPO for 24 hours and that after that she “may have small pieces of toast!”

The patient returned home with her husband.

Four hours later he checked on her, and she was found deceased in bed.

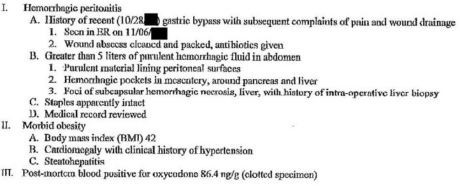

An autopsy was done with results shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Patient’s autopsy results.

The patient’s family filed a lawsuit against both emergency physicians, both hospitals, and the surgeon.

At deposition, the attorneys asked the second emergency physician if he felt he released an unstable patient in light of her last documented heart rate of 142 bpm. He responded, “She was not unstable in my opinion. She was alert, talkative, pleasant. Her pain had been relieved. She had a blood pressure of 130/80. She had a good sat. I wouldn’t call her unstable.”

In addition to a medical malpractice claim, the lawsuit specified an EMTALA violation as well.

The EMTALA claims were dismissed by the judge because the second emergency physician never identified an emergency medical condition. (Note: Failing to detect an emergency condition is an acceptable defense against an EMTALA violation, though clearly not against a malpractice claim.)

The medical malpractice claims were settled out of court. The exact details are unknown, but a seven-figure settlement would be typical.

Discussion

This case provides an example of the dangers of discharging patients with tachycardia. Discharging a patient with tachycardia is not universally contraindicated in cases where the tachycardia is relatively mild and the patient has a credible low-risk explanation. However, this patient met neither criteria. A heart rate of 142 bpm (with an upward trend) in the setting of recent gastric bypass was a recipe for disaster.

The defendant’s claim that the patient was not unstable with a heart rate of 142 bpm was misguided.

On the second visit, there was documentation that the patient had not filled her prescriptions. While it is frustrating when patients return to the emergency department without following the instructions they were given at the time of the previous discharge, it doesn’t mean their bounceback visit can be dismissed. In fact, a return visit may be the last chance we have to prevent a catastrophic outcome.

The second emergency physician clearly did not want to do any workup or bother the surgeon again. Instead of making one more phone call to transfer the patient, he ended up dragging his partner and the surgeon into a multiyear litigation process. Don’t follow in the footsteps of this physician and miss your final opportunity to reverse course and save a life.

Dr. Funk is a practicing emergency medicine physician in Springfield, Missouri, and owner of Med Mal Reviewer, LLC. He writes about medical malpractice at www.medmalreviewer.com.

Dr. Funk is a practicing emergency medicine physician in Springfield, Missouri, and owner of Med Mal Reviewer, LLC. He writes about medical malpractice at www.medmalreviewer.com.

See the records

Visit www.medmalreviewer.com to review the full medical records or send Dr. Funk an email with your thoughts on the case at admin@medmalreviewer.com.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Don’t Be Shy When Evaluating Patients Who Return to the ED”