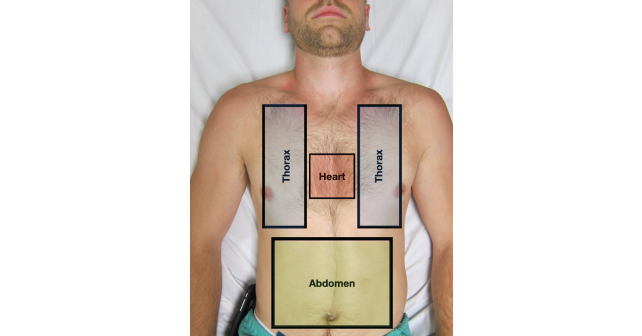

Alternatively, in the blunt trauma patient with hemodynamic compromise, the thorax and abdomen should be the first two boxes evaluated by eFAST. This approach can clarify the need for early tube thoracostomy in the setting of massive hemothorax/pneumothorax or help guide the trauma team to pursue operative stabilization if massive hemoperitoneum is noted. In contrast, significant hemopericardium following blunt trauma is an uncommon and often non-survivable event, and thus the pericardium should be scanned after the other two boxes are rapidly and thoroughly evaluated.7

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 41 – No 09 – September 2022The eFAST exam is highly specific for free fluid in the abdomen and highly sensitive for pneumothorax, hemothorax, and pericardial effusion.8–10 Therefore, most emergency physicians utilize the eFAST in unstable patients to decide whether or not the patient needs rapid operative stabilization or can undergo further CT imaging.

2. Goal-Directed Communication

The eFAST examination findings must be properly communicated when working alongside your trauma colleagues. There should be bidirectional communication with the trauma team leader to facilitate appropriate and timely intervention while always taking into account the patient’s clinical status. The eFAST is not a binary test—the interpretations are nuanced and the assessment of the “three boxes” should be interpreted in real time. Communication to the trauma team should be in a granular or detailed manner so that these results can properly be incorporated into the care of the patient.

When communicating these results to the trauma team, it is critical to interpret both positive and negative eFAST exams in the context of the patient’s clinical status. For example, in the patient with a blunt abdominal injury and a trace amount of free fluid in Morrison’s pouch, this source of bleeding is unlikely the cause of significant hypotension as the hemorrhagic volume needs to be much greater than the minimum 150 to 200mL required to be visualized on an eFAST.8 This is in contrast to advanced trauma life support (ATLS) hemorrhagic shock classifications where blood pressure would not typically lower until class III shock (1500–2000mL of blood loss).11 While this should be reported as a “positive” abdominal component of the eFAST examination for documentation purposes, it is imperative to communicate to the trauma team leader that this degree of free fluid in the abdomen does not clinically correlate with the patient’s hemodynamic instability. Alternative or concurrent injuries in the other two boxes (e.g., thorax or heart) or the possibility of an unstable pelvis/retroperitoneal injury or long bone injury and/or neurogenic shock should also be considered.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 5 | Single Page

No Responses to “eFAST 2.0: Refining an Integral Trauma Exam”