Emergency departments face significant challenges in patient management and concomitant increases in regulatory and reporting requirements. Some regulatory requirements are matched to transparency mandates for items that will be reported to the public, such as the Hospital Compare measures from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. And notably, the issues of timely care, flow through the emergency department, and safety incidents in the ED waiting room have activated regulators, The Joint Commission, and the general media.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 37 – No 11 – November 2018ED leaders have tackled the critical imperative to reduce the number of persons who enter the emergency department but leave prematurely. The Emergency Department Benchmarking Alliance (EDBA) has worked with other organizations to develop definitions that provide consistency in reporting. With the input of ED leaders who recognize the temptation to cheat on this reporting element, it was necessary to develop an inclusive term that would incorporate all patients who leave before they are supposed to and would not provide gaps for patient encounters to be missed in the ED reporting systems.

The participants in the third Performance Measures and Benchmarking Summit have published the results of the sessions in which ED definitions were developed, with incomplete ED patient encounters termed “left before treatment complete” (LBTC).1 This single definition provides the most complete accounting for all patients who leave the emergency department before they are supposed to, and it includes patients who leave before or after the EMTALA-mandated medical screening examination, those who leave against medical advice (AMA), and those who elope (ie, simply walk out without speaking to anyone).

The EDBA uses this single statistic to compile the annual number of patients who are recognized by the emergency department but leave prior to completion of treatment. This provides the most complete accounting for all incomplete encounters, and it delivers a great comparison statistic.

The Stats

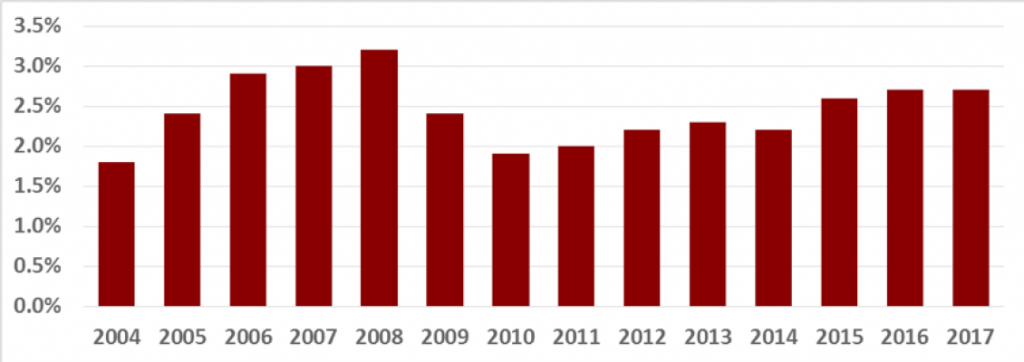

A number of studies have related ED walkaway rates to flow rates, and across a 14-year time frame, the EDBA data have found walkaway rates relate to volume, ED type, time to first contact with a licensed provider, and overall ED flow.2,3 The LBTC rate has trended lower across EDBA hospitals over the prior 14 years (see Figure 1).

For the past eight years, the EDBA study has evaluated various time intervals and their potential contribution to the LBTC rate. Table 1 shows the eight-year data on LBTC and median door-to-provider and door-to-decision times for admitted patients. Despite a consistent drop in median door-to-provider times, the LBTC rate has gone up, possibly because during those eight years the door-to-decision time has crept higher. That time is generally under the control of the emergency physician, and it offers an opportunity to focus on efficiencies that will move critical information to emergency physicians so they can make a quality decision.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

One Response to “Emergency Department Inefficiency Drives Poor Quality”

December 2, 2018

Rob Beatty, MD FACEPGood article. In the time frame reported, there has been a major push for EMR conversion due to meaningful use requirements. Some of those EMRs impact house-wide processes as a whole, which could cause significant increases in lab/radiology turnaround time, and add additional human steps to workflow that were not in practice previously. Have you considered evaluating these additional data points and seeing how they fit into your analysis?