The COVID-19 pandemic has stressed our health care system in many ways. It has strained hospital capacities, caused shortages of supplies and equipment, and required health care workers to take extra shifts and work without days off. Many physicians, nurses, and other health care workers have contracted COVID themselves, some requiring hospital stays and long recoveries. ACEP Now interviewed several emergency physicians who had COVID-19 to hear about their personal experiences and what they learned by being the patient. Responses have been edited for length and clarity.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 40 – No 04 – April 2021Do you know how you got COVID-19?

GB: My hospital initially had a good number of COVID cases as the pandemic hit. I also saw a very ill elderly woman who fit the bill for COVID in mid-March. Might have been a false negative.

PD: Not sure how I caught it, but I was caring for multiple patients with COVID-19 in the days before I became ill. I had been having chills for two days but didn’t check my temperature until the end of the second day. My son, daughter, and wife all got sick within two to three days of each other.

TF: Most likely from an intubation I performed that was rushed and didn’t have all the PPE needed. We didn’t have HEPA filters on our machines set up on every mechanical ventilation until mid-April.

JG: I do not know where I contracted it. I suspect via community spread. Our ED COVID-19 counts were still relatively mild at the time and all my recent patient encounters had been while wearing full PPE. I was supposed to work a night shift on October 30. My wife jokingly called me “Mr. Sniffles” because I had some mild nasal congestion. I heavily debated still going to work given the mild symptoms. Ultimately, I decided to activate sick call, which turned out to be the right decision!

LL: We had a work outbreak.

Dr. J. David Gatz and his family having dinner while he was in COVID isolation.

J. David Gatz

JP: Not really. I’d been seeing lots of COVID patients and don’t remember a specific moment or situation where I could’ve got it.

KS: Not a clue. I worked treating more COVID patients than any other patients for nine months. I took two weeks off, not being around anyone, and then got COVID.

What did it feel like?

GB: My symptoms never included respiratory trouble. My biggest issues were fatigue and a need for significant sleep, fever, malaise, and loss of taste. Cognitive processing was tough, too.

PD: The worst part was the overwhelming fatigue. Even though I didn’t lose my sense of taste or smell, the mere act of trying to eat was too strenuous. I barely ate anything for a week. Taking a shower required a two-hour nap afterwards. After about seven to 10 days, I started coughing and had difficulty breathing. My wife, who’s a physician, too, said I had rales throughout, so I probably had pneumonia, though I never had a chest X-ray. My pulse ox dropped to 90 percent. I told myself that if I dropped to 88 percent I would have to go to the hospital. Fortunately, I didn’t require hospitalization. I also felt remorse that my colleagues were fighting so hard for their patients and I was not able to be there to help them. By the time I got back to work, the major surge was behind us.

TF: I had severe headache (like it was going to explode), fever, SOB, and body aches for the first three to four days and another week of exhaustion and loss of taste and smell.

JG: My symptoms were fortunately quite mild: some congestion, muscle aches, and eventually loss of taste and smell. I was terrified that my symptoms would progress. The worst part was the stress of worrying about my family. I was terrified I would infect them. I had immediately isolated myself in the basement. My wife would leave food at the top of the stairs, which I would retrieve while wearing a mask and gloves. I only emerged from the basement in the dead of night to put away my dishes, wiping everything I touched with bleach. Thankfully, my wife consistently tested negative, and my daughter never developed any symptoms. It was tough on all of us, and lonely. We still tried to have family dinners. I’d sit at the bottom of the stairs with the basement door open. It was the only time during the day we really got to see one another.

RJ: The first week, I had tremendous fatigue (sleeping 12 hours a day) and no appetite (I lost 10 pounds). It was the second week that I realized I had the virus when I “broke” quarantine and went to lunch on my birthday. The glass of wine I had tasted terrible!

JP: The first two to three days were the worst with fever, unbelievable headache, and pain all over. The anosmia part was terrible, being isolated and having one of your senses abolished gives you the sense of depersonalization. I got a CT scan and had mild pneumonia, no desaturation, but mild dyspnea.

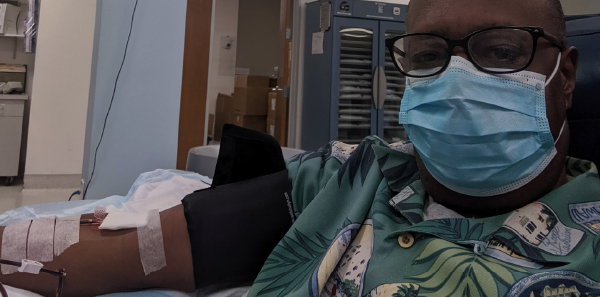

KS: I initially had horrible fatigue, body aches, loss of taste, and terrible thirst. On Christmas Eve, my boss picked me up at home and took me to the ED. I had bilateral COVID pneumonia, was severely dehydrated, had a glucose 600 in DKA, and was septic. I was admitted to the ICU for five days, med/surg for four days, and rehab for three days as I was hypoxic. I continued to recover for three weeks and then became severely hypoxic—sats in the low 70s with any exertion (long COVID symptoms).

I went back to the ED with a CT scan showing persistence of the bilateral pneumonia. I was placed on prednisone 40 mg for five days and then 20 mg for five days. The lowered dose saw the severe hypoxia return. I was placed on supplemental oxygen, which allowed me to do ADL for short periods. I was placed on inhaled steroids since the oral steroids blew up my sugars, about 400–450. In about four days on PulmoCort [budesonide] inhaled steroids, I was off the supplemental oxygen. Within a week I was able to ride a bicycle a short distance (I was a mountain bike racer before COVID) with a lot of coughing and deep breathing. I feel this exercise has really helped clear out my lungs so I could continue to progress.

How long was your recovery?

GB: I had symptoms one week or so. After the seventh or eighth day, I started to improve. Perhaps part of this was recognizing that I had made it past the point of developing the late developing respiratory issues. By post-symptomatic day 10, I was back working. I had a glossitis that is just now improving. Since the infection, I need about an hour more sleep a day. Maybe that’s seasonal or related to being 52. I had no residual effects on my lungs. I’ve returned to my half marathons.

PD: I started to feel better after about two weeks and was able to return to work three and a half weeks after I was diagnosed. I don’t think I have any residual symptoms.

JG: They had me on a standard 10-day isolation. Physically, I felt fine by the end of those 10 days and returned to work. At home, we kept the isolation going for another full week, just to be safe. At this point, I don’t seem to have any lingering symptoms other than perhaps a mildly diminished sense of smell.

RJ: I felt back to normal several days later (about 10 days total), but it took several weeks for my sense of taste to return. Fortunately, I never developed any cough or breathing issues and have had no lasting symptoms.

LL: I was really ill for one week, but the fatigue lasted for several weeks after I was “recovered.”

JP: Fourteen days, going on 30 with pulmonary rehabilitation. I still have dyspnea on exertion, and I’ve been having insomnia and trouble remembering words. Neurologists tell me that’s normal post-COVID.

KS: Initial symptoms Dec. 11. I really felt I had improved by Feb. 11. So, two months duration with initial COVID and long COVID. Only now mild fatigue and mild SOB, but part of that could just be deconditioning.

JW: A week or so. I was never very sick, so never really worried that I would get ill. My son got it from me and had more severe symptoms, so I was a bit worried about him. Due to my mild symptoms, I worked two shifts in the ED before I started really feeling sick. This was very early when there was a lot of fear in the media and public. [The media found out that I worked while having symptoms] and they made it sound like I dragged myself into work just to spew viral particles on patients. The mayor called me out, and criminal charges were entertained for a brief period. There were death threats against me in social media. Fortunately, no one knew my name.

What did you learn by being in the patient role?

GB: This coronaviral infection crosses the pathological spectrum; it certainly involves multiple organ systems, including the CNS. The pathology is widespread and variable. I didn’t need any medical care but the psychological impact for a few days was interesting. Waiting for a cough to develop that could lead to a significant decline, hospitalization, etc. provides insight into anxiety of the unknown and the impact of the psychology of a disease process. Particularly interesting: Is it better to know the pathology and process of a disease or not?

PD: I was very worried about the course the illness was going to take with me. Reading the various blogs and message boards didn’t help. I finally had to stop following them. It was just too depressing and scary. I have never been really sick, and the sense of fear and helplessness was difficult to deal with. That is something that I understood was normal and was experienced by my patients and their families, but this illness brought it into sharper focus for me.

TF: Since I became ill early in the pandemic, there were many unknowns. I felt the fear and mental health consequences, like many. There was a day that I thought I was going to die because my HR would jump to 180s just from a walk from the bedroom to the bathroom.

JG: It’s scary, and tough not just on the patient. My isolation left my wife singlehandedly taking care of herself, our daughter, and me. I was furious with my inability to assist.

RJ: The most difficult part of the entire experience was being in quarantine for two weeks in my bedroom. My wife brought me meals. Fortunately, and surprisingly, she never got any symptoms. I also hated being home while my colleagues were doing everything they could to take care of patients in my community who were starting to get ill.

LL: It is very difficult to be in a situation where you don’t feel like doing anything. I am a contracted worker, so my income was affected like so many other people. Going back to work when you don’t feel 100 percent was also difficult. I felt like I needed to be at work to take care of people but honestly did not feel up to the strenuous 12-hour shifts. However, I needed to go back for a lot of reasons, including the fact that other people were ill and it made a lot of holes in the schedule.

JP: That everyone lives this experience differently, and circumstances (age, family, general activity) play a very important role in isolation. Also, uncertainty is a big enemy—you don’t know if you’re going to be OK or not.

KS: There is a significant difference between nursing and being a physician—they are completely different outlooks on patient care. Rehab centers are not prepared to treat the pulmonary complications of long COVID (approximately 30 percent of severe COVID cases). In a significant number of severe COVID cases, DKA can develop, especially in pediatric patients.

What do you want people to know about this disease?

GB: Viral infection with SARS-COV-2 is a spectrum of clinical illness. We are capable of rapidly addressing these sort of crises as seen by current vaccine developments and improvement in clinical care practices. Also, public health is the single most important aspect of our species’ medical care. The outbreak and the mass of illness we saw were all fairly accurately predicted based on knowledge, work, and investigation. Vaccines and the simple act of separating fresh water from contaminated water are two things that do more than the work of all physicians combined for humanity. More emphasis and appreciation of primary preventative, community, and national health care policy must emerge from this. I am cynical regarding any improvement for our country. Politicizing and ignoring this outbreak might be seen as crossing the line to the immoral. The vast number of physicians who have openly advocated and aligned with those politicizing this are an embarrassment to our profession and bring forth a better understanding of why the U.S. has some of the worst outcomes in health care among industrialized nations. In my state, we were almost certainly penalized for our voting history and having states compete for resources is a political ideological failure. But the fracturing extremes of this nation make it such that I do not know if we will do better.

PD: COVID-19 is not just the flu. People I know became very ill and some died. This is something we have never experienced before in our lifetimes. So many ventilators and critically ill patients. I hope that people take the illness seriously, follow guidelines that are scientifically developed and GET VACCINATED! However, do not let fear consume you. Be sensible and we will get through this.

JG: Don’t ignore symptoms, even mild ones. My only initial symptom was nasal congestion. I had debated still going to work and might have infected numerous colleagues. We’re used to pushing through mild symptoms and abhor activating our colleagues for sick call. The reality is we must take all such symptoms seriously and be ready to activate sick call. Early isolation can work. I was pleasantly surprised that my wife and daughter were never infected. Infecting our families is a fear many of us share. With early isolation, it is possible to get COVID and not infect your family!

RJ: It is pretty clear that everyone’s susceptibility is different. I did everything to protect myself both at work and when outside my home and yet still somehow managed to get infected. While each person can try to reduce the risk of contracting the virus, nothing puts the risk at zero. Anyone with risk factors should be even more cautious.

LL: It is not a made-up … disease. During the epidemic I lost my father to COVID-19. It has affected our family a lot.

JP: That is very relevant in one’s life, even life-changing. Family and the support you receive is basic in recovery and managing all of the other symptoms.

KS: Have faith you will get better! Get the vaccine so you don’t have to go through COVID the hard way. Take precautions, like wearing a mask and maintaining physical distancing. I started PulmaCort early in the disease process. If you test positive and have SOB, you might consider that too. In severe cases, accept you will have “long COVID.” It is coming. Check your sugars on a daily basis if you get COVID.

Participants

Garth Barbee, MD, FACEP

Garth Barbee, MD, FACEP

West Linn, Oregon

Diagnosed March 2020

Patrick Davis, MD, FACEP

Patrick Davis, MD, FACEP

Old Bridge, New Jersey

Diagnosed March 2020

Tsion Firew, MD, MPH, FACEP

Tsion Firew, MD, MPH, FACEP

New York, New York

Diagnosed April 2020

J. David Gatz, MD

J. David Gatz, MD

Columbia, Maryland

Diagnosed October 2020

Ramon Johnson, MD, FACEP

Ramon Johnson, MD, FACEP

Laguna Niguel, California

Diagnosed March 2020

Lillian Lockwood, MD, FACEP

Lillian Lockwood, MD, FACEP

McLouth, Kansas

Diagnosed October 2020

Juan Antonio Pérez-Cervantes

Juan Antonio Pérez-Cervantes

Mexico City, Mexico

Diagnosed January 2021

Kevin Schmidt, DO, FACEP

Kevin Schmidt, DO, FACEP

Bakersfield, California

Diagnosed December 2020

Jason Wagner, MD, FACEP

Jason Wagner, MD, FACEP

St. Louis, Missouri

Diagnosed March 2020

Pages: 1 2 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Emergency Docs Share Their Experiences Recovering from COVID-19”