The ambulances keep rolling, and for many years, the majority of their trips ended with a patient entering the emergency department. But a new paradigm is evolving, and it is likely that significant changes are ahead in the relationship between the providers of emergency medical services (EMS) and the ED.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 33 – No 12 – December 2014The 2013 Emergency Department Benchmarking Alliance (EDBA) data survey gathered performance measures from more than 1,300 participating EDs. This survey has a 10-year trend line demonstrating that a very consistent percentage of ED patients arrive on an ambulance stretcher and that a large number of those patients will receive diagnostic testing in the ED, initial treatment, and then admission to an inpatient unit of that hospital or another one offering a higher level of service.

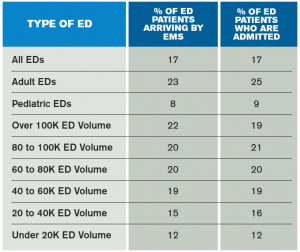

Specifically, the EDBA survey asked member EDs to report the percentage of patients who arrive by EMS and those who arrive by EMS and are admitted from the ED to the hospital. EMS arrival rates are higher in those EDs with larger volumes and by far highest in EDs serving adults, where about 23 percent of patients arrive in an ambulance. Ambulance arrival rates average around 12 percent in smaller-volume EDs and about 8 percent in EDs that serve only pediatric patients.

In 2013, about 17 percent of patients seen in the ED arrived by EMS, a percentage that has been very consistent over the last 10 years. There is close correlation between EMS arrival and the overall admission rate from the ED, as shown in Table 1, with larger-volume and adult-serving EDs having higher admission rates and higher EMS arrival rates.

There are evolving models of unscheduled care that have EMTs and paramedics providing a variety of patient care services outside of the traditional transportation model.

Trending the EDBA data over the past 10 years finds that EMS arrivals and admission rates are very stable and that patients arriving by ambulance continue to represent higher acuity than those arriving in a private automobile or other conveyance. Table 2 demonstrates that about 39 percent of EMS-arriving patients are admitted. That means patients arriving by other means have a significantly lower admission rate, at about 12.5 percent.

There are evolving models of unscheduled care that have EMTs and paramedics providing a variety of patient care services outside of the traditional transportation model. The term that has been applied is mobile integrated healthcare practice (MIHP). This is a novel and evolving health care delivery platform intended to serve a range of patients in the out-of-hospital setting by providing patient-centered and team-based care using mobile resources. This has included programs to provide follow-up care for patients released from inpatient status back to their home, patients with recurrent admissions for long-term health problems like congestive heart failure, and patients with a variety of health problems who have demonstrated frequent use of EMS service in the past.

The new models of MIHP have included a variety of EMS providers, types of vehicles, and targeted groups of health care consumers. The Cleveland Clinic and other systems have put mobile stroke units in service, mirroring programs developed in Germany.1 Some systems utilize trained paramedics to do recurrent visits to at-risk patients.2 Many EMS systems have developed software that identifies “familiar faces” in the EMS system and then locates those patients under nonurgent circumstances to interview them and determine which community services might serve them in a more efficient manner.3

Is the use of mobile health services a mark of quality health care? Will improving field care reduce costs and improve outcomes? Will it decrease less-urgent uses of EMS and reduce transports of these lower-acuity patients? If that occurs, will reducing ambulance traffic be good for the ED? Might it reduce ED diversion and crowding conditions?4

It is likely that there will be a variety of models that are useful to patients in need of mobile services, whether they are scheduled or unscheduled. If the triple aim is applied to emergency care, it would suggest that effective patient care would be provided at the right place, at the right time, with the right equipment and personnel, at the right price, and, of course, for the appropriate value. That requires cooperation in development among EMS leaders and medical directors, ED leaders, and those who pay for the services or provide grant funding for the innovative programs.

39 percent of EMS-arriving patients are admitted, meaning patients arriving by other means have a significantly lower admission rate.

For years, ambulances have served patients with higher levels of illness and injury. Those patients are the very essence of the emergency department. But when EDs get too crowded, there is a controversial process called diversion that sends ambulance patients to other hospitals. It is not clear that diversion results in better outcomes for anyone and costs the hospital large amounts of marginal revenue.

Patients who are high-frequency users can be identified by case managers, hospitals, EDs, or the EMS system so that a better system of care can be developed for those individuals. Attempting to set up that system to function at the time of a 911 call is probably not the best target. Some have tied a 911 call to an EMTALA responsibility and the mandate for a medical screening examination before the patient is released.

So emergency physicians are going to be entwined in meetings to develop regional models of care that match local needs and resources and lead to appropriate use of both ambulances and EDs. With subsequent discussions with payers and politicians, there is an opportunity to move the system forward to the benefit of patients and the communities that pay for the 911 system.

James J. Augustine, MD, FACEP, is director of clinical operations at EMP in Canton, Ohio; clinical associate professor of Emergency Medicine at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio; vice president of the Emergency Department Benchmarking Alliance; and on the ACEP Board of Directors.

James J. Augustine, MD, FACEP, is director of clinical operations at EMP in Canton, Ohio; clinical associate professor of Emergency Medicine at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio; vice president of the Emergency Department Benchmarking Alliance; and on the ACEP Board of Directors.

References

- Zeltner B. Cleveland Clinic announces top ten medical innovations for 2015. Cleveland Plain Dealer. October 29, 2014.

- Knodel S. Exploring the use of paramedics to aid in reducing hospital readmissions. Nebraska Medicine. 2014;13(1):7-8,15.

- Tadros AS, Castillo EM, Chan TC, et al. Effects of an EMS-based resource access program (RAP) on frequent users of health services. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2012;16:541-547.

- Burt CW, McCaig LF, Valverde RH. Analysis of ambulance transports and diversions among US emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47:317-26.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Emergency Medical Services Arrivals, Admission Rates to the Emergency Department Analyzed”