In light of ACEP’s approaching golden anniversary, ACEP Now took a look back at the last 50 years of emergency medicine and the people and trends that have shaped the specialty.

Explore This Issue

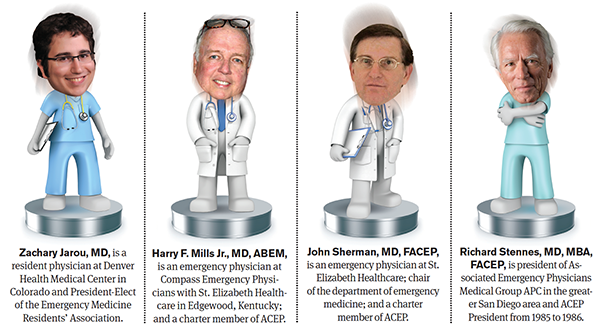

ACEP Now: Vol 35 – No 12 – December 2016ACEP Now Medical Editor-in-Chief Kevin Klauer, DO, EJD, FACEP, recently discussed the history of the specialty with two emergency physicians who have been members of the same EM group for their entire 45-year careers, a past ACEP President, and one of the next generation of EM leaders. The group discussed the origins of emergency medicine, how it has grown and changed over the years, and what the future holds. Here are some highlights from that conversation.

Moderator

Kevin M. Klauer, DO, EJD, FACEP, is an ACEP board member; chief medical officer–emergency medicine, chief risk officer, and executive director–patient safety organization at TeamHealth; ACEP Now medical Editor-in-Chief; and assistant clinical professor, Michigan State University College of Osteopathic Medicine, East Lansing.

Kevin M. Klauer, DO, EJD, FACEP, is an ACEP board member; chief medical officer–emergency medicine, chief risk officer, and executive director–patient safety organization at TeamHealth; ACEP Now medical Editor-in-Chief; and assistant clinical professor, Michigan State University College of Osteopathic Medicine, East Lansing.

Participants

KK: John, what was emergency medicine like when you and Harry started?

JS: Harry and I started at St. Elizabeth’s July 1, 1971. We had no hospital status, no department, no representation on the executive committee, no leadership positions in the hospital, and, of course, we had no specialty status. We had to learn to make our own way. We look at things differently now. There’s a lot more corporate medicine, and we have the benefit of clinical and even financial guidelines, regulations, and rules that ACEP has been instrumental in developing for us over the years. A lot has changed.

KK: John and Harry, what prompted you to start an emergency medicine group?

HM: John and I were on a ski trip while we were interns, and both of us had been working in emergency rooms as interns. Four of us in medical school decided to form a group. John and another were interning at St. Elizabeth’s. I was interning up at Indiana University in South Bend. Another gentleman was in Minnesota. The possibility came about for St. Elizabeth’s Hospital—who was using residents, family practice guys, and others to staff the emergency department—to form a group.

JS: I still have the original letter that I sent to the hospital administrator when Harry and I and two others had decided to form this group. This is a one-page proposal, $15 an hour was what we asked for, and we offered to have a group of four physicians committed to St. Elizabeth’s, committed to a career in emergency medicine. He signed it, and off we went.

ZJ: Today’s residency graduates are being nearly inundated with the amount of job offers that we are receiving. When you guys were setting up your initial groups, was it more so out of necessity because there wasn’t anybody offering the sort of position you were looking for or because you always had this entrepreneurial drive?

HM: Our hospital didn’t have a need. They had been staffing the emergency department with different people, fly by night, and we came up with a proposal. After working in the emergency department as interns, we essentially ran the department. We had staff on call and another resident above us, but I enjoyed the “episodic-ness” of emergency medicine.

KK: Graduating residents are inundated with opportunities because there are far many more opportunities available than there are residency-trained, board-certified, or board-eligible emergency physicians. Back when you started your group in 1971, I’m sure you had to convince others who wanted to do other things with their life to pursue emergency medicine: “Come join us and be a part of this group while we are considering developing and evolving with this specialty.”

RS: In 1971, when we first started here in San Diego, the idea of emergency medicine as a specialty was kind of unknown. It was just going to work in the pit! It was typically covered by anyone who could be coerced. Of course, there were no paramedics in those days. There weren’t any trauma centers. We were the knife and gun club, and if you heard a honking horn outside, that meant there was a heroin overdose being dumped. We learned after a while, rather than extricate them at great personal risk, we’d just give them Narcan right in the back seat, and off they’d go. We delivered a lot of babies in the ED because women would wait in the parking lot until they were crowning. At that juncture, CAL/ACEP was in its infancy. The importance of leadership in the early days became very clear. That’s when EMPAC [the Emergency Medicine Political Action Committee] came along. Medicare was a problem. Around 1975, we marched on Washington with Terry Schmidt [our part-time lobbyist]. As our advocacy needs grew, along came NEMPAC. There were things we couldn’t do in the ED. We couldn’t intubate in the daytime because that was anaesthesia. We could do it at night because they weren’t around.

KK: That was a great summary. Knowing that we are in a better place as a specialty, which era did you prefer to practice emergency medicine in?

RS: Well, that’s not easy to answer, Kevin. It was certainly fly by the seat of your pants for sure. That part was exciting. I had no idea of what I didn’t know; none of us did. Going back to that perspective of the ’70s, we would do things that would be unthinkable today. If someone was really nasty, we paralyzed them and talked to them, “You know, when I bag you, you breathe. When I don’t bag you,” you’d stop bagging for a while, “you notice you don’t breathe. So I’m going to wake you up in a little while, and I want you to be really nice. Got it?” When they woke up, they were always nice.

Today, the rules are entirely different. The expertise we bring to the bedside today is much more exciting. Back then, we didn’t have ultrasound, CT, or MRI. We had an IV, some blood, and that was about it.

KK: Zach, which world would you like to work in? In yesterday’s emergency medicine or today’s?

ZJ: Great question. I think it’s comforting to hear people who’ve been around for a while saying that they’re just as happy to practice today as they were initially. The entrepreneurial side of me thinks that it would have been advantageous to have been around 40 years ago. I think that starting your own group is challenging in today’s environment. At the same time, I think a lot of the major battles have been fought, so it’s certainly easier for folks to walk into emergency medicine today and be a respected member of the hospital and be respected as a specialist. I certainly thank everyone that came before us in terms of fighting all of those battles. In terms of where emergency medicine is headed in the future, I think that we’ve heard a lot more talk about being part of this acute care continuum and looking at how emergency medicine can get more involved in the prehospital environment, doing more things in terms of community paramedicine, keeping people out of emergency departments, how emergency physicians are more well-positioned to deal with unplanned episodic care, and looking at how new technologies are going to enable telemedicine to allow remote evaluation of patients.

JS: In the early ’70s, a resident we helped train in the community told me that a leader, Don Thomas, told him that there were three things you needed to know in emergency medicine: Was the patient alive or dead? Are they going to live or die in the next 30 minutes? And did they need to be admitted, or could they go home? Like Richard was saying, there were times I did things I was never trained to do as a rotating intern, but it saved people’s lives. Instead of having somebody to show you how to do something, you did it first, then you showed somebody else.

The entrepreneurial side of me thinks that it would have been advantageous to have been around 40 years ago. I think that starting your own group is challenging in today’s environment. — Zachary Jarou, MD

After working in the emergency department as interns, we essentially ran the department. We had staff on call and another resident above us, but I enjoyed the “episodic-ness” of emergency medicine. — Harry F. Mills Jr., MD, ABEM

There were things we couldn’t do in the ED. We couldn’t intubate in the daytime because that was anaesthesia. We could do it at night because they weren’t around. — Richard Stennes, MD, MBA, FACEP

This kid needed an airway, so I had to do a cricothyrotomy on him, and I sent him off to Children’s. The kid did great, but I was a nervous wreck for the rest of the shift. — John Sherman, MD, FACEP

KK: I have a question for all three of you who’ve practiced much longer than Zach and I have. Was there ever a situation where you knew you were the only option for the patient?

RS: It was my first shift in 1971, and the moonlighting radiology resident couldn’t go to work that night and said, “Could you go down there and work tonight?” I showed up, and they said, “Who are you?” I remember a patient walking in with an ice pick hole to the left of his sternum. He sat on the gurney; he was getting worse. I listened to his chest—Rice Krispies. I got an X-ray, and there was widening of his mediastinum, and I thought, “What the hell is this?” He promptly died on me. Had this guy come in a year later after I learned about opening chests, I probably could have at least performed a pericardiocentesis. It didn’t take very long before I started doing things I really had no training in, and it was either, “You’re going to die, or I’m going to try to do this.”

JS: I had a young kid who was hit by a car, and most of the damage was to his face. He essentially had no airway. This kid needed an airway, so I had to do a cricothyrotomy on him, and I sent him off to Children’s. The kid did great, but I was a nervous wreck for the rest of the shift.

HM: Well, you had to change your underwear fairly regularly when we were working in those days. That’s improved.

JS: I think it really was more fun, but the patient care is much better now. There’s just no question about it. We now have to put up with patient satisfaction surveys, be sure our charting is perfect, and follow all of the regulations. None of that was an issue back then.

RS: One of the questions you asked was about forming a group. In my case, it just sort of happened. My first partner was Nat Rose. We were in the Navy and got out in July 1972. We started working 16-hour nights for the first two years, rotating, Nat and I, and we were getting about $20 an hour. We had an 80 percent contract to start. About four months into it, the hospital CEO said, “This doesn’t work. We think we want to pay 60.” That pushed us into independent billing. Inadequate Medi-Cal payments were a big issue. That made it clear that CAL/ACEP was a vehicle that we absolutely needed to have to make all of this work, and so three of us in my group, Bill O’Riordan, Roland Clark, and I, all became presidents of CAL/ACEP. We just evolved into things we needed to be and developed affiliate organizations, whether it was billing, insurance, or marketing, in order to make it all work. There was no plan. It was serendipity, but it turned out pretty well.

KK: So necessity bred invention. What about John and Harry? Did you feel that the support and development of ACEP helped you and your group?

JS: There was national ACEP, but California was a little ahead of Kentucky. We didn’t even have a state chapter when Harry and I started. In fact, I got together with three other physicians around the state; we actually formed the Kentucky chapter of ACEP. National ACEP was huge because it gave us contact with other physicians who had common problems. There were meetings, and it provided a tremendous educational resource for us.

KK: Zach, from your perspective, what is the reputation of emergency medicine now among students who are deciding what specialty they want to practice?

ZJ: I think, reflecting on a couple of things that were said, that there have always been challenges in emergency medicine, and the challenges 40-plus years ago are a little bit different than the challenges that today’s physicians are facing. It sounds like ACEP and other organizations are crucial in addressing these challenges, and I’m glad that those organizations are still around to help us today. I think a lot of people don’t appreciate the history as much as everyone who was there and fighting these early battles. Nowadays, I think students probably take for granted that emergency medicine is a well-respected specialty with lots of resources within its own department at most every single major academic medical center and that emergency physicians are respected members of the health care team. Emergency medicine gets more and more applicants every year. It’s very popular. I think that it seems on the same level as any medical specialty now, thanks to all the hard work from our pioneers.

JS: I get the sense from a lot of the younger doctors coming out of residency programs that ACEP is almost viewed as serving more the corporate or the business end of emergency medicine rather than the practicing physician. As a result of that, a lot of people don’t even belong to ACEP. I’ve always felt being a member of ACEP was a good thing. Do you feel that some of that is being promulgated in the residency programs?

ZJ: As a resident with a busy clinical load, sometimes it’s hard to appreciate the effect that ACEP has made in terms of lobbying to make sure that emergency physicians get fair reimbursement and are being treated properly within the health system. I think some residents may not understand the total impact that being part of ACEP has, and I think that one of the challenges is conveying that value to them as they transition out of residency, where their dues are often being paid for them, to demonstrate the value so they’ll continue to pay when it comes out of their own pockets.

RS: Part of our problem with messaging to younger people is maybe we’re not communicating what ACEP really does in terms of preventing things from happening in state capitals and preventing bad things from happening in Washington as well as making good things happen. Any one decision there can make a lifetime of difference for any one doctor and pay for their dues for a lifetime. Many may not know or understand what organized medicine, ACEP for the emergency medicine profession and the AMA in general, really does to make their lives possible, to protect their practice, and help them earn a living.

KK: Listening to Zach’s passion, it’s equal in magnitude but from a different perspective. Richard made a comment about the importance of “carrying the water” by advocating for and leading the specialty, and that resonates with me, and I’m sure it does with others, too. If the younger physicians out there are allowed to participate and carry some of that water, not as a burden but as an opportunity, then will they be more invested in the future of the specialty and with ACEP? We have to look for those opportunities. What would you want people to do so that what you’ve built doesn’t erode and is protected?

HM: Richard speaks about carrying the water, but I think you have to chop the wood, too. I think we have to remember that we don’t exist if there aren’t patients. I had to always remember that they were the reason why we were there, to take care of people, and as long as you remember that the patients are the reason you’re there, then all this other small stuff simply matters a whole lot less.

KK: The whole specialty owes a debt of gratitude and thanks to physicians like Harry, John, and Richard. If they had not accomplished what they had with yesterday’s emergency medicine, Zach and today’s emergency physicians would not be able to build a more perfect future for tomorrow’s emergency medicine.

5 Responses to “Emergency Medicine Founders Discuss Origins of the Specialty, How It’s Changed, and What the Future Holds”

December 18, 2016

Cindy Pearsall Sussman MD FCEPI was sorry to not see a credit given to Dr David Wagner, the real “grandfather of Emergency Medicine” in your article. Dr Wagner was a general surgeon at the Medical College of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia and noted the immense need for an Emergency Medicine residency program. His was the first, and paved the way for many more to come. As a graduate of that program, I am proud to say that we were well prepared for just about anything that came our way. Dr Wagner deserves credit for having the foresight and energy to get the field on its feet.

December 18, 2016

Cindy Pearsall Sussman MD FCEPCorrection- Dr Wagner was a pediatric surgeon

December 18, 2016

MarianKevin,

Thank you for an insightful article regrading the history of emergency medicine and where we are headed.

I find it ironic that there are two articles in this edition of ACEP eNow discussing diversity in emergency medicine, however, your interview panel lacked diversity. I am certain that this was not intentional, but it certainly highlights the unawareness at times of this particular issue.

December 19, 2016

Kevin Waninger MD FACEPEven more important, Dr. David Wagner was a great role model and a really nice man. I am a better doctor, and even more important, a better colleague, friend and father, because of my interaction with Dr. Wagner.

November 22, 2018

Kathleen Nakfoor, Ed.D, MBA, MSIS, RNI had the privilege of working with Dr. John Wiegenstein, MD and Dr. Eugene Nakfoor, MD from 1970 to 1975. I was told “history is being made in this emergency room” and know this to be a fact. I recall working with Dr. Wiegenstein the nights before he head off, yet, to another meeting to battle for EM as a speciality. He entertained us with stories of his less than impressive luggage when checked into the presidential suite. I was well aquatinted with stories of progress being made in EM.

What has been overshadowed by the enormity of ACEP formation and EM becoming a specialty, are the historical changes that were made in emergency department management. I recall Eugene Nakfoor, MD, also a founding ACEP member, telling me stories of the fact no one knew how to bill for services, such a practice was unprecedented. He garnered “departmental status” in which he controlled all hiring and firing of the entire staff.. He and the nurses developed the original scribe system, not the one in existence today. There has never been such a well managed emergency department using the scribe; actually a pivotal individual with whom the department was organized.