Editor’s Note: The ACEP Council hosted a Town Hall meeting on mergers and acquisitions on Oct. 24, 2015, in Boston. Here is an edited transcript of the discussion, including the introduction by then-Council Speaker Kevin M. Klauer, DO, EJD, FACEP, chief medical officer–emergency medicine, chief risk officer for TeamHealth, and ACEP Now medical editor-in-chief.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 35 – No 01 – January 2016Introduction

Kevin Klauer, DO, EJD, FACEP

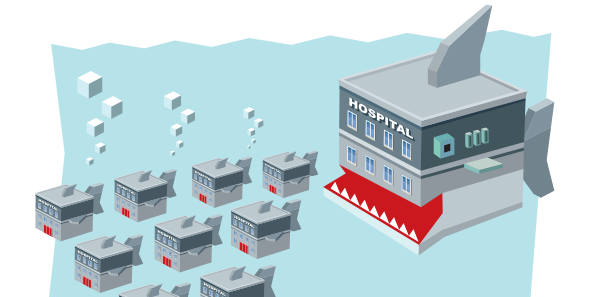

This is our Town Hall meeting and should represent a topic that is really important to the practice of emergency medicine, our specialty, and beyond: mergers and acquisitions. Many of us may not know a lot about this process and how it could impact us, but I think it’s time we discussed it so that we are all more informed about mergers and acquisitions in medicine. That’s why I titled this “Mergers and Acquisitions: The Medical Shark Tank.” I tried to get Mark Cuban; he still hasn’t responded to the request. I’ve asked Ricardo Martinez, who has a wealth of broad health care knowledge, to moderate this session.

Moderator

Ricardo Martinez, MD, FACEP, chief medical officer for North Highland Worldwide Consulting and assistant professor of emergency medicine at Emory University in Atlanta.

Participants

Brent Asplin, MD, MPH, FACEP, chief clinical officer for Mercy Health in Ohio

Savoy Brummer, MD, FACEP, vice president of practice development at CEP America in Belleville, Illinois, and chair of the ACEP Democratic Group Section

Ray Iannaccone, MD, FACEP, president of EmCare

Jay Kaplan, MD, FACEP, President of ACEP; director of the patient experience for CEP America in Emeryville, California; and a practicing clinician in the emergency department at Marin General Hospital in Greenbrae, California

RM: I think we have a very good group to talk about mergers and acquisitions, which are happening fairly quickly. The United States is seeing a lot of consolidation in many different markets. I’ll start with Dr. Asplin: what is driving hospital consolidation, and is that a good thing or a bad thing?

The first thing to consider is that, relative to other industries, we’re actually on the front end of a consolidation movement. We’re really still quite fragmented in health care. The majority of primary care practices in the country are still using three providers or less. Look at other industries, like how many U.S.-based global airlines there are now. Look at telecommunications, and soon we may only have three large for-profit health insurers that are national in scope. There are three basic financial drivers: liquidity and balance sheet drivers, operational metrics, and purchasing power. It’s about spreading fixed overhead costs to a larger base and gaining efficiency. It’s about building a stronger balance sheet to be able to withstand shocks to that balance sheet. Even though the cost of capital is at a historical low, it’s also about maintaining a strong rating to be able to access capital at rates that are favorable. You also want purchasing power in terms of supply chain and some asymmetry of negotiations. Those are the financial drivers, but I think uncertainty is one of the biggest drivers of consolidation. Even if all is going well for an independent community hospital, things can go from strong performance to the brink of solvency quickly, particularly with the dramatic swings we may be seeing in reimbursement. That is why you are going to see more hospital consolidation unless you have a compelling brand where you can continue to go at it as a single institution. Children’s hospitals would be some of the classic examples of a single-institution compelling brand. I think consolidation is a good thing for the system overall because we will lose fewer access points in hospitals because of it than we would if those hospitals remained independent.

RM: Great, thank you. Two things to throw on your plate: one of those is a business concept called rule of threes that comes out of a Georgia Tech business school. Basically, everything consolidates down to three. Look at cellular companies. You mentioned the insurance companies consolidating to three. Secondly, everyone’s figured out it is time to go after the children’s hospitals, so they are under great stress right now. Savoy?

SB: I would completely agree with all those drivers. I think uncertainty has another more common name, which is fear, and a lot of hospital systems have a fear of obsolescence. They’re looking to consolidate to eliminate much of their competition in other areas. They’re looking for new sources of revenue to, perhaps, offset some of their losses in other areas. Obviously, increasing their market share allows them to do that.

RM: Thank you very much. Dr. Iannaccone, in your role, you have a large perspective across the country.

RI: The only thing I would add is that as hospitals and health systems are looking at what they have to do over the next few years to maintain what thin margin they have, a small community hospital looks at the daunting task in terms of IT, purchasing, upkeep, or putting together a robust physician network. I think they recognize they need a certain amount of scale to do that. I’ve been told by health system CEOs that they know that the number of patients admitted to their hospitals is going to go down. They’re going to need a bigger, broader base of people to fill the beds while they’re in the gap years until they’re getting paid for quality.

RM: Thank you. Jay?

JK: Well, the single biggest driver of health care reform is cost. As organizations look to decrease their expenses, two of the ways they do that is to eliminate competition and to eliminate unnecessary expenses. One of the ways they can eliminate those items is through purchasing power, which Brent mentioned. Another strategy is to develop what are being called HROs, or highly reliable organizations. You can’t have 15 doctors with each wanting to do things their own way. You have to figure out what’s the one “our way.” When I was chief of emergency medicine for a 10-hospital health care system, we looked at the number of antibiotic prescribing regimens we had for community-acquired pneumonia; we had 37. By narrowing it to 10, we were able to save the system a couple of million dollars. I think that’s what organizations are doing as they are merging. They are looking to develop more consistency across all their different facilities and, by doing so, they reduce costs.

Well, the single biggest driver of health care reform is cost. As organizations look to decrease their expenses, two of the ways they do that is to eliminate competition and to eliminate unnecessary expenses. —Jay Kaplan, MD, FACEP

RM: Let’s turn it to emergency group consolidation. I wanted to separate those because they are two different things. I’ll ask the same question, and I’ll start with Jay. What’s driving that emergency group consolidation, and is that a good thing or a bad thing?

JK: There are a couple of things driving emergency medicine group consolidation. One of the most important things is physicians must have a say in terms of their practice environment, in terms of their pay, how hard they’re working, and the resources they have. What’s driving emergency medicine group consolidation is those same hospitals that are now consolidating are looking at their costs and seeing that they have some product lines that are money makers and others that are losers. They’re thinking about their groups, which offer not only emergency medicine services but hospitalist services and maybe anesthesia, and asking, “Through consolidating those services, can I improve quality and decrease cost?” That is, from my perspective, what’s driving acquisitions and consolidation. A lot of smaller groups are saying, “We see the writing on the wall. What can we do to protect our lifestyle and to protect our practice environment? We do not want to get swallowed up where we are going to lose control.” Interestingly enough, if you look at physicians nationwide, by 2025, 70 percent of physicians will be employed. That’s changing the whole paradigm for physicians who went into practice. Is it a good thing or a bad thing? I’m going to put on my ACEP hat and say that it’s good as long as we can maintain a sense where physicians have some control over their practice environment.

I don’t care what the payment model is: modified fee for service, alternative payment model, or value-based purchasing. If it doesn’t lead to taking costs out of the system, it’s not sustainable. Period. —Brent Asplin, MD, MPH, FACEP

RM: Dr. Iannaccone?

RI: Well, I think I’ll answer that question by telling you briefly about the experience my group, Emergency Medical Associates, went through because we just did it less than a year ago. We had 37 years as a fiercely independent democratic group. We were painfully democratic in terms of how we did things. So why would we feel we have to make a decision like this? When I say “we,” I mean that as the CEO, I reported to a board of nine physicians, partners who worked and owned the group. It was all run by physicians. Together, we put together a strategic plan, looked at it, and said, “Holy cow, we’re not going to be able to get that done. We don’t have enough money, we don’t have the size, and we don’t have the speed to compete or to solve the problems.” The problems seemed to be coming quicker than our solutions were, so we needed to find a partner that would allow us to have some of the things that Jay just mentioned to retain some of the autonomy that we had without the ownership. I think that’s what groups are looking for when they consolidate: a pooling of resources.

RM: Great. Savoy?

SB: I think ideally most people would look at consolidation among professional services in a positive way if you are going to improve overall performance for patient care, if you’re going to improve the patient experience, and lastly, if you can do so in a setting maintaining or decreasing the cost curve. However, the majority of times we’re seeing many groups, especially independently owned groups, consider consolidation because of a failure, at least a perceived failure, of their ability to compete in the marketplace. I think, again, that there’s a large amount of fear from the eyes of the smaller independent groups. Lastly, I do believe that there’s a generational component in which there are many folks around retirement, and they’re looking for different means to monetize their practice. If you look at how Wall Street and private equity have subsequently performed after many of those acquisitions, you’ll see that performance hasn’t necessarily been ideal. I know that within my particular democratic group, we see over 5 million visits a year, but $100 million of our annual revenue comes from private equity or publicly held practices that had ultimately failed.

RM: Thank you. Dr. Asplin?

BA: I’m going to answer this from a hospital system perspective. We have 23 hospitals in seven markets across Ohio and one market in western Kentucky. Many of you are familiar with W. Edwards Deming, one of the most important quality-improvement process engineers of the 20th century. One of my favorite quotes of his is, “Uncontrolled variation is the enemy of quality.” I don’t know what the right answer is in terms of the right number of groups for a system like ours to work with, but I know it’s not 23 different groups. The answer, at least for the near term for us, isn’t to employ everyone, but we can’t work and get to scale fast enough if we have too many partners to work with. From a hospital system perspective, how can we get at the next level of quality, safety improvement, and cost reduction? I don’t care what the payment model is: modified fee for service, alternative payment model, or value-based purchasing. If it doesn’t lead to taking costs out of the system, it’s not sustainable. Period. We have to get at cost, and there are tens of millions of dollars of unnecessary costs and quality failures in our system due to uncontrolled clinical variation. You can’t get at those without clinician and physician engagement. That’s why if it’s leading to costs coming out, uncontrolled variation coming down, and quality improving, then I think the consolidation of hospital-based groups—emergency medicine being one of them—is a good thing.

Council Town Hall highlights will continue in the February issue.

No Responses to “Emergency Medicine Leaders Discuss Drivers of Hospital Consolidation at ACEP15 Council Town Hall”