Written from the perspective of an emergency physician who also runs a weekly minor fracture clinic, this column will highlight a few key teaching points for commonly missed and commonly mismanaged ED orthopedic cases. This debut column will deal with pediatric distal radius fractures.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 36 – No 10 – October 2017The Cases

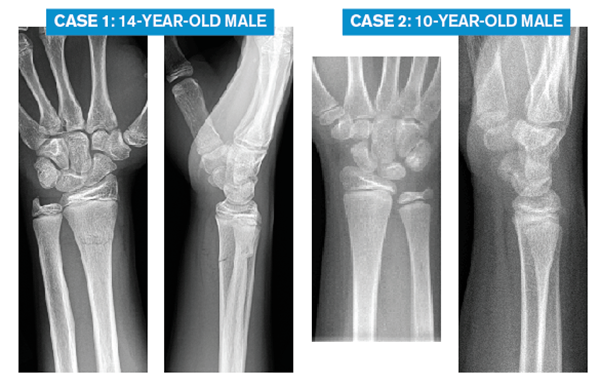

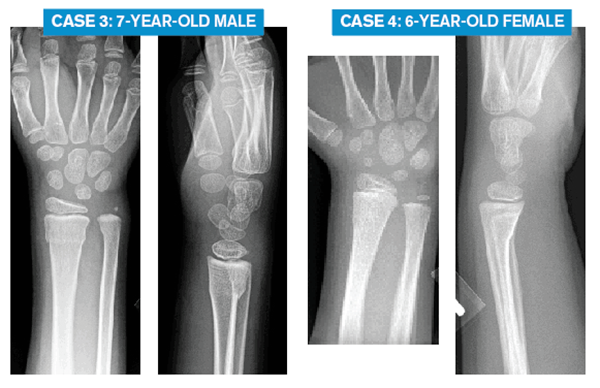

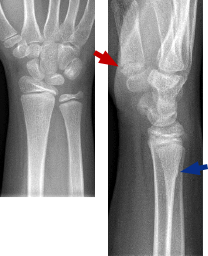

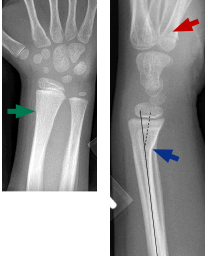

Here are X-rays of four pediatric patients with isolated wrist injuries after a fall. Each is mildly swollen and tender at the distal radius, closed, neurovascularly intact, and without scaphoid (or other carpal) tenderness.

What is your diagnosis, emergency department treatment, and follow-up plan for each?

The Challenge

Of the above four cases, the radiology report for each may read, “buckle fracture of the distal radius.” One case is a simple buckle fracture, and it tends to be overtreated in the emergency department. For the other three cases, they require well-molded immobilization in the emergency department. However, two of the cases should be molded in flexion; the third case, in extension. Optimal ED management requires us to recognize the subtle differences between these pediatric distal radius fractures.

The Clinical Pearls: Pediatric Distal Radius Fractures

- Simple dorsal buckle fractures are stable. Treat for comfort and protection. Removable splints are fine.

- Transverse fractures (also called complete or bicortical fractures) can be subtle on X-ray. If the dorsal buckle fracture extends to the volar side or if the distal fragment is dorsally angulated, then it is not a simple dorsal buckle fracture. For these fractures, the distal fragment tends to shift dorsally; the fractures should be molded in flexion.

- Volar buckle fractures are less common, more difficult for emergency physicians to appreciate, and more likely to be mismanaged; these should be molded in extension.

- Don’t solely rely on the radiologist’s report. It may not offer enough detail. It may be wrong. Make sure you see the X-rays, not just the report!

Introduction

If you see kids in your emergency department, then you’re managing pediatric fractures. Distal radius fractures are the most common.

Fractures can be stable or unstable. Stable fractures will not shift with activities of daily living. They need comfort and protection while healing. A simple dorsal buckle fracture of the distal radius is a good example (as in Case 2).

Unstable fractures have a tendency to shift. Some kids with distal radius fractures need a reduction (not covered in this article). Those cases are more impressive, and it is more intuitive that those fractures have a tendency to shift back to their pre-reduction position and should be molded in the opposite direction to prevent that possible shift.

However, unstable fractures are not always so obvious. As in three of the above cases, recognizing the instability of some fractures can be quite subtle.

The ED challenge in managing pediatric distal radius fractures lies not so much with the common simple dorsal buckle fracture since it does not require specific immobilization or with the significantly angulated fracture that clearly needs reduction. Rather, the challenge lies in recognizing the subtle fractures that may shift, identifying the direction they may shift, and ensuring proper ED immobilization and follow-up.

About 10 percent of injuries diagnosed by emergency physicians as simple buckle fractures of the distal radius are subtle examples of more complex injuries.1 Subtle radiologic abnormalities result in significantly different ED management. Recognition requires astute radiographic interpretation.

Injury Patterns

Simple dorsal buckle fractures of the distal radius are very common. They are caused by a compression-type force applied to relatively soft, immature bone. The child falls on the outstretched hand. The volar aspect of the distal radius impacts the ground, and the force results in the commonly seen buckle fracture on the opposite compressed dorsal aspect of the distal radius.

Simple dorsal buckle fractures can be subtle on the lateral view—but the fracture line does not extend to the volar cortex and there is no angulation (the planes of the proximal and distal fragments are parallel/anatomic). Case 2 is such an example. Simple dorsal buckle fractures are stable injuries that require treatment for comfort and protection. Numerous studies have shown simple buckle fractures do well with removable splints or soft bandages.2–9 Treating with a circumferential cast is no better for patients and often less preferred by them.5–9 Practically speaking, in our emergency department, treatment would either be a removable premade Velcro forearm splint or a removable slab. (Fiberglass is preferred over plaster since it’s lighter and molding is not required for simple dorsal buckle fractures.) Follow-up should be arranged for proper guidance and return-to-sports advice. Typically, that would take place in the fracture clinic in a week or two. Depending on practice location and referral patterns, primary care physicians can certainly be an option for the follow-up of simple dorsal buckle fractures of the distal radius.1,10

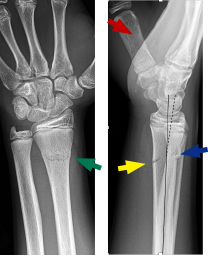

Occasionally, a buckle is seen, but on closer inspection, the X-ray reveals a more significant fracture type. If a greater force is applied to the volar side (ie, fall at greater speed or from height, like monkey bars), then a more significant fracture may occur, one that extends across both the dorsal and volar cortices (see Case 1). In some cases, the fracture line may not clearly extend to the volar side, but the distal fragment is mildly angulated dorsally (see Case 3). These are not simple dorsal buckle fractures. They are transverse fractures (complete or bicortical).

Part of the confusion with this fracture pattern is the various terms used to describe these fractures. In addition to transverse, complete, and bicortical, some clinicians may call them non-buckle fractures. Some orthopedic surgeons and radiologists might call these greenstick fractures, while others would argue that is incorrect since a greenstick fracture breaks on the convex/distracted side but these fractures occur on the concave/compressed side.

While it’s easy to understand the confusion, it is important to recognize that, whatever the label, these fractures can be subtle on X-ray, are more likely to shift, and require well-molded immobilization. Fractures tend to shift in the direction the original force was applied. When falling on an outstretched arm, the force is applied to the distal fragment in a volar-to-dorsal direction, so the fracture tends to drift dorsally. To discourage this tendency, molding should be in the opposite direction in flexion. Since molding is important, plaster is preferred over fiberglass. Plaster has inherently better molding properties (reference: pretty much every orthopedic textbook!). A radial gutter splint (with connected plaster on both the dorsal and volar sides of the radius) that is properly applied and molded in flexion works very well. Follow-up should be arranged within a week with orthopedics since X-rays often will be repeated to check alignment for these potentially unstable fractures.

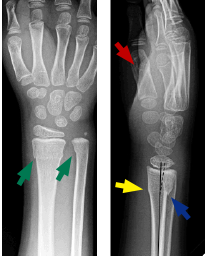

Finally, the last case (Case 4) involves the most common ED molding mistake seen in our fracture clinic: failure to recognize the volar buckle fracture. In these cases, the distal radius fracture tends to shift volarly. A helpful tip: When looking at the lateral wrist X-ray, always identify the thumb first as this defines the volar side of the forearm. If a buckle is seen on the volar cortex, the force must have come in the dorsal-to-volar direction, and when asked, patients often report a fall on the back of their hand, not on their outstretched arm. If such fractures shift, they shift volarly, so molding must be in the opposite direction in extension.

A safe approach for pediatric volar-based buckle fractures of the distal radius, particularly if there is any volar angulation of the distal fragment, is to mold them into extension. Again, if molding is important, plaster is preferred over fiberglass. A well-molded radial gutter splint molded in extension (optional to extend above the elbow) with orthopedic follow-up within a week is recommended.

A Final Point

The radiology report of each of the above four cases may read, “buckle fracture of the distal radius.” Radiologists are not necessarily aware of these subtle yet clinically relevant X-ray differences. Errors will occur if we, as emergency physicians, rely solely on the radiologist’s report. We must review the images ourselves, not just read the report!

See below for a review of our four cases.

I hope this helps you manage your pediatric patients with distal radius fractures. A special thanks to ACEP and Dr. Kevin Klauer for the opportunity to contribute. The goal is to highlight ED patients with commonly missed/mismanaged musculoskeletal injuries and offer strategies to help on your next shift. Comments on this column and suggestions for future ones are most welcome.

Dr. Sayal is a staff physician in the emergency department and fracture clinic at North York General Hospital in Toronto, Ontario; creator and director of CASTED ‚Hands-On‘ Orthopedic Courses; and associate professor in the department of family and community medicine at the University of Toronto.

Dr. Sayal is a staff physician in the emergency department and fracture clinic at North York General Hospital in Toronto, Ontario; creator and director of CASTED ‚Hands-On‘ Orthopedic Courses; and associate professor in the department of family and community medicine at the University of Toronto.

References

- Koelink E, Schuh S, Howard A, et al. Primary care physician follow-up of distal radius buckle fractures. Pediatrics. 2016:137(1):e20152262.

- Abraham A, Handoll HH, Khan T. Interventions for treating wrist fractures in children. Cochrane Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD004576.

- Davidson JS, Brown DJ, Barnes SN, et al. Simple treatment for torus fractures of the distal radius. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(8):1173-1175.

- West S, Andrews J, Bebbington A, et al. Buckle fractures of the distal radius are safely treated in a soft bandage: a randomized prospective trial of bandage versus plaster cast. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25(3):322-325.

- Khan KS, Grufferty A, Gallagher O, et al. A randomized trial of ‘soft cast’ for distal radius buckle fractures in children. Acta Orthop Belg. 2007;73(5):594-597.

- Plint AC, Perry JJ, Correll R, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of removable splinting versus casting for wrist buckle fractures in children. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3):691-697.

- Williams KG, Smith G, Luhmann SJ, et al. A randomized controlled trial of cast versus splint for distal radial buckle fracture: an evaluation of satisfaction, convenience, and preference. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29(5):555-559.

- Witney-Lagen C, Smith C, Walsh G. Soft cast versus rigid cast for treatment of distal radius buckle fractures in children. Injury. 2013;44(4):508-513.

- Karimi Mobarakeh M, Nemati A, Noktesanj R, et al. Application of removable wrist splint in the management of distal forearm torus fractures. Trauma Mon. 2013;17(4):370-372.

- Koelink E, Boutis K. Paediatrician office follow-up of common minor fractures. Paediatr Child Health. 2014;19(8):407-412.

Patient 1: 14-year-old male

Patient 1: 14-year-old male Patient 3: 7-year-old male

Patient 3: 7-year-old male Patient 2: 10-year-old male

Patient 2: 10-year-old male Patient 4: 6-year-old female

Patient 4: 6-year-old female

4 Responses to “Emergency Medicine Pearls, Pitfalls for Treatment of Pediatric Distal Radius Fractures”

November 19, 2017

Matt JaegerThanks so much! I appreciate your article very much. I often treat simple buckle fractures with a removable splint, but after reading your article I wonder if I may have done the same with a volar buckle fractures in the past. I will certainly change my practice. Thanks again.

July 30, 2018

Arun SayalThanks Matt.

There are tons of little pearls from our specialist colleagues – subtleties that help us manage us patients better.

Glad it helped.

Arun

November 19, 2017

AWHGreat article, and has absolutely changed my practice. Thank you Dr. Sayal!

July 30, 2018

Arun SayalThanks AWH!