In late summer 1914, as World War I began, Europeans on both sides of the conflict greeted war with unrestrained zeal. The common belief was that the war would be over by Christmas. But by the end of the year, a million were dead and there was no end in sight. It was the world’s first encounter with the dark side of modern progress and the first modern mass destruction.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 33 – No 12 – December 2014

Former underground city beneath the trenches. Photographed March 11, 2013. Picardy, France.

Until this past summer, few knew of the existence of a hidden world of World War I—that is, until the discoveries and photographs of Dallas emergency physician Jeffrey Gusky, MD, FACEP, were featured in National Geographic magazine and The New York Times and on BBC television (http://www.bbc.com/news/world-29409433).

WWI soldiers’ graffiti. Photographed Jan. 30, 2013. Picardy, France.

In haunting black-and-white images, Dr. Gusky has documented the art and artifacts left behind by troops in hundreds of underground cities beneath the former trenches of the Western Front in France. A fine-art photographer, emergency physician, and explorer, Dr. Gusky gained the trust of French farmers under whose land are buried these testaments to the hopes, dreams, and fears of tens of thousands of soldiers from both sides who lived and worked there throughout the war.

The images are striking: panoramic shots of miles-long subterranean cities, an abandoned dining table still set with wine bottles and canteens, a pencil drawing of lovers kissing, and a bas-relief sculpture of a French soldier whose face is half gone.

Dr. Gusky hopes that through his efforts, we will become aware of the compelling parallels between then and now. “My work as a fine-art photographer is very much about helping people to see how modern life can blind us to danger,” he said.

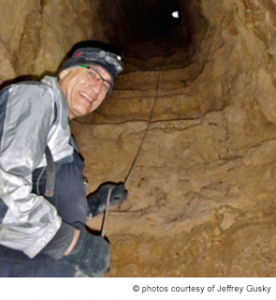

Dr. Gusky during a photo shoot, at the base of a stairway leading from tunnels to the trenches above ground.

An Intuitive Switch

Dr. Gusky’s interest in fine-art photography was sparked by an emergency department colleague’s collection of black-and-white photography. In 1995, Dr. Gusky decided to tour Nazi concentration camps during the harsh Polish winter. Just before leaving, he bought a professional-grade camera body and a single lens. On a bitterly cold, overcast day at Płaszów concentration camp, depicted in the movie Schindler’s List, he discovered a small part of the camp that was largely unknown, even to locals. “That place is where my second career as a fine-art photographer began,” he said. “It was as if an intuitive switch flipped on inside, and it has remained on since.” Dr. Gusky explained that he had photographed what he felt in that haunted place, using his intuition as a guide. When he returned to Texas and others saw these photographs, “they also described them as haunted. There was a level of emotion that people could feel.” Dr. Gusky said.

Connection to the Bedside

Since 1995, Dr. Gusky has visited and documented many sites where modern genocide and mass destruction have occurred. “What underlies events in all these places—Poland, Moldova, Romania, the battlefields of World War I in France and Belgium—is what happens when people become dehumanized by the incomprehensible scale of modern life,” he observed.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

No Responses to “Emergency Physician Documents Hidden World War I Art, Artifacts in Photographs”