Sometimes, the most clear-cut problems don’t necessarily have straightforward solutions.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 37 – No 01 – January 2018

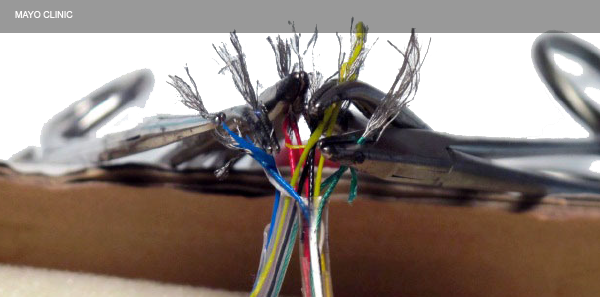

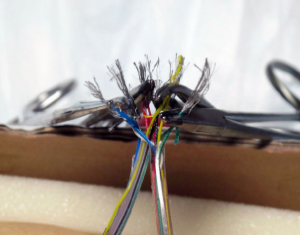

Figure 1: Successfully reconnected LVAD battery pack. Each cut wire was spliced back together, allowing the LVAD to restart.

William Resnick

A 67-year-old male who had a past medical history of ischemic cardiomyopathy and had a left ventricular assist device (LVAD) placed arrived in our emergency department via ambulance in cardiac arrest after cutting the driveline to his LVAD. He had been at home sitting on the toilet and was attempting to cut off his Depend underwear when he cut the wire to the LVAD. The device’s alarms went off, and his wife came into the room. She reported that the patient had a syncopal episode but was intermittently awake and responsive. There was no report of any other complaints prior to this event. His wife called EMS. When they arrived, the patient was minimally responsive, with his LVAD nonfunctional. He then lost consciousness and was pulseless. CPR was started en route to the hospital. The Mayo Clinic cardiothoracic surgical team contacted us regarding further recommendations, which included vasopressors, standard CPR, and our own Depends, as needed.

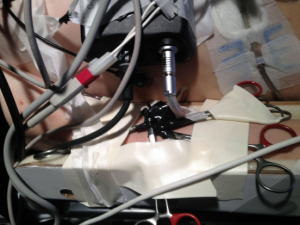

Figure 2: Hemostatic clamps were used to reconnect the LVAD driveline.

Mayo Clinic/Reprinted from J Emerg Med. 2014;47(5):546-551, with permission from Elsevier.

The patient’s past medical history included-end stage heart failure, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, and hypertension. His social history included no reported tobacco or alcohol abuse.

The patient arrived at our facility about 20 minutes after the wires were cut. His initial physical exam showed an unresponsive elderly male with CPR in progress, no obvious signs of trauma. His pupils were equal, and he had no spontaneous movement. Vital signs showed sinus tachycardia, and his blood pressure was not obtainable. Although he had no spontaneous movement on arrival, he briefly opened his eyes and began moving his extremities before losing consciousness again. The remainder of his examination was typical for a patient in cardiopulmonary arrest.

He was intubated on arrival, and he was initially resuscitated with IV fluids and vasopressors.

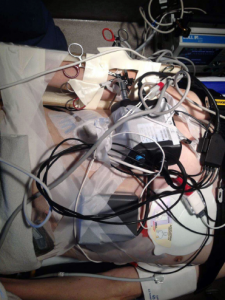

Figure 3: Electrical tape was used to secure the hemostats, which were taped to the patient’s arm.

William Resnick

After initial evaluation, it appeared quite clear that this was actually an electrical problem. Unfortunately, the battery pack was left at the patient’s house, but the house was quite close to the hospital. A police officer who was in the emergency department went with lights and sirens on to the house to recover it. Although installing an LVAD may be beyond the scope of an emergency physician, “MacGyvering” a solution certainly is not. I have an extensive background in construction, so while waiting for the battery pack, our staff and I used wire strippers to remove the outer plastic coating of the cable and exposed five separate colored wires. When the battery pack arrived, we completed the same procedure on the wires connected to the battery. Each individual wire was spliced back together, reconnecting the LVAD to the battery pack (see Figure 1). The wires were made of some type of fiber-optic material and required hemostats to maintain the electrical connection (see Figure 2). The LVAD immediately restarted, and perfusion improved dramatically. The patient’s condition stabilized, and other than some mild tachycardia, he had no other cardiac issues. Electrical tape was used to secure the hemostats, which were then taped to the patient’s arm to prevent any dislodgment (see Figure 3).

Pages: 1 2 | Single Page

3 Responses to “Emergency Physician Solves Malfunctioning LVAD with Electrician Skills”

January 17, 2018

Mark BuettnerWow!

January 20, 2018

akpAnd I thought orthopods were the only docs who used home depot tools on patients. way to go Dr Resnick!

January 25, 2018

Robert KormosSo we have had over 25 years of support from our clinical Biomedical Engineering group that provide round the clock coverage 365 days a year for our LVAD patients. Besides helping with LVAD patient and hospital staff training they have done exactly what is described in this article by repairing urgently a severed drive-line for a patient saving his life. This service is provided by our own in-system company called Procirca.

kormosrl@upmc.edu