For the last decade and a half, patients presenting with acute ischemic stroke have had one active option for emergency intervention: intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (tPA). In the context of ongoing controversy, pervasive conflicts of interest, and a paucity of conclusive trials, use of tPA for stroke has increased but hardly taken hold. Many professional organizations still oppose its mandated use, and the basic assumptions of its efficacy continue to be challenged.

Explore This Issue

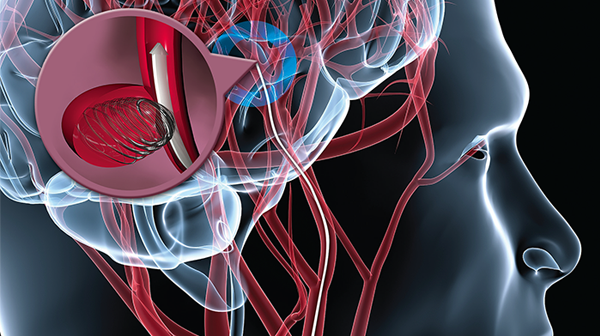

ACEP Now: Vol 34 – No 05 – May 2015Putting all the tPA-related issues aside for a moment, let’s talk about the next-generation of therapy: endovascular intervention. This is not a new innovation, as clinicians have been exploring this therapy in earnest since the early 2000s. Why are these devices of such great interest given the development of tPA? Because one of the best-kept secrets about tPA, the “clot buster,” is that it doesn’t bust clots. In the largest meta-analysis of angiographically confirmed intracranial occlusions, sustained early recanalization was achieved with tPA only 46.2 percent of the time.1 Comparing this with the observed 24.1 percent spontaneous recanalization rate, tPA clearly has a maximal ceiling for benefit if only one in five additional patients achieved reperfusion. The aim of endovascular intervention is to overcome this practical limitation to the effectiveness of tPA.

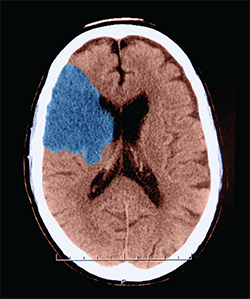

Ischemic stroke. This axial (cross sectional) CT of the head shows a classic appearance of an acute middle cerebral artery infarction (stroke) (shown here in blue). This patient showed a hyperdense MCA sign. This sign is indicative of thrombo-embolic occusion of the MCA.

Image Credit: Medical Body Scans / Science Source

However, the initial foray into such technology produced what might best be described as killing machines. The initial devices, detailed in the Mechanical Embolus Removal in Cerebral Ischemia (MERCI) and Multi-MERCI trial results from 2005 and 2008, had high rates of complications just related to the procedure—arterial perforations and fracture of the stent-retrieval devices.2,3 Coupled with high National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) scores, patients undergoing these procedures had correspondingly high mortality. Over time, however, the devices and techniques improved yet to no avail. The 2013 literature produced a constellation of negative trials: Mechanical Retrieval and Recanalization of Stroke Clots Using Embolectomy (MR RESCUE), Intra-arterial Versus Systemic Thrombolysis for Acute Ischemic Stroke (SYNTHESIS), and Interventional Management of Stroke (IMS) III.4–6 Like the earlier trials, these targeted patients with large-vessel anterior circulation occlusions, severe and disabling strokes for which recanalization with tPA is particularly poor. Fewer procedural complications occurred in these trials, but all three failed to show an additive benefit of endovascular intervention over standard therapy.

What a Difference a Year Makes

The end of 2014 brought us the Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial of Endovascular Treatment for Acute Ischemic Stroke in the Netherlands (MR CLEAN), the first major unambiguously positive trial of endovascular therapy versus usual care.7 The trial randomized 500 patients with large-vessel anterior occlusions; 32.6 percent of patients achieved functional independence (modified Rankin Scale 0–2) in the endovascular cohort, compared with 19.1 percent with standard care, without any corresponding increase in intracranial hemorrhage or mortality. With a median NIHSS score of 18 and few favorable outcomes with standard care, these were clearly patients for whom alternative treatment options were worth investigating. The generally dismal outcomes of the selected patients almost certainly played a role in finally measuring a meaningful difference in outcomes. The other notable achievement in this trial, performed between 2010 and 2014, was the rate of recanalization of 75.4 percent with endovascular intervention, far exceeding the 32.9 percent occurring in standard care. Prior endovascular trials failed to demonstrate such a disparity in reperfusion, owing either to lower success rates with endovascular intervention or higher rates of success with tPA. While the most skeptical of us would take these results with a grain of salt, such reservations are not held by the true believers. More specifically, such reservations were not held by the manufacturer of the devices supplied to the ongoing endovascular trials. Upon publication of the MR CLEAN results, three sponsored trials—Endovascular Treatment for Small Core and Proximal Occlusion Ischemic Stroke (ESCAPE), Extending the Time for Thrombolysis in Emergency Neurological Deficits–Intra-Arterial (EXTEND-IA), and Solitaire With the Intention For Thrombectomy as PRIMary Endovascular Treatment (SWIFT PRIME)—used this opportunity to conduct unplanned interim analyses of their trials for efficacy.8–10 The results, presented at the International Stroke Conference in February 2015, were universally positive. Indeed, not only were the results positive but the magnitude of favorable outcome differences was even more pronounced than in MR CLEAN. Patients receiving standard care achieved modified Rankin Scale 0–2 at rates ranging from 23 percent to 40 percent, while functional independence was achieved in the endovascular cohorts at rates ranging from 53 percent to 71 percent. Correspondingly, like MR CLEAN, these trials showed endovascular recanalization rates higher than prior trials, ranging from 74 percent to 94 percent.

We can expect to see slow changes to regional stroke triage systems to incorporate the availability of endovascular interventions. Unfortunately, with any such innovation, enthusiasm is almost certain to lead to indication creep beyond the patients selected for recent trials.

Of course, as anyone who’s been to Las Vegas knows, it helps to quit while you’re ahead. There are major issues with performing unplanned analyses and early stoppage of trials. Termination of enrollment increases the confidence intervals around the primary outcome and the chance of a type I error (ie, that a treatment difference will be detected when none exists). Somewhat ameliorating the issue in this case, all three trials stopped early were similarly consistent in their findings, and therefore these results are probably as reliable as such evidence from sponsored clinical trials can be. It should also be noted all three of these trials utilized imaging-based selection criteria using preprocedure perfusion imaging. Patients were required to have small underlying ischemic cores surrounded by a substantial penumbra supplied by collateral circulation. The astute academician will point out MR RESCUE also randomized 68 patients with penumbral patterns, and their outcomes were degraded by endovascular intervention. However, that trial was performed between 2007 and 2011, and the success rates with devices were much lower at that time. Proponents of endovascular therapy and their sponsors are understandably elated by these results. We can expect to see slow changes to regional stroke triage systems to incorporate the availability of endovascular interventions. Unfortunately, with any such innovation, enthusiasm is almost certain to lead to indication creep beyond the patients selected for recent trials. These trials enrolled an average of a mere one to two patients per month, or about one in 100 patients screened. The long history of negative trials should also strongly caution us against resource intensive overuse beyond carefully selected patients. The most recent registry publication of patients selected just on the basis of expert practice, Systemic Thrombolysis in Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke and Internal Carotid ARtery Occlusion (ICARO-3), showed no difference in favorable outcomes associated with endovascular intervention and substantially increased intracerebral hemorrhage.11 Selection for endovascular intervention should be tightly restricted to patients resembling the recent trials to provide the most reliable potential benefit. Despite a long and complicated history, there is finally cause for guarded optimism with regard to emergency interventions for stroke. Watch for changes coming to a hospital near you.

References

- Rha JH, Saver JL. The impact of recanalization on ischemic stroke outcome: a meta-analysis. Stroke. 2007;38(3):967-973.

- Smith WS, Sung G, Starkman S, et al. Safety and efficacy of mechanical embolectomy in acute ischemic stroke: results of the MERCI trial. Stroke. 2005;36(7):1432-1438.

- Smith WS, Sung G, Saver J, et al. Mechanical thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke: final results of the Multi MERCI trial. Stroke. 2008;39(4):1205-1212.

- Kidwell CS, Jahan R, Gornbein J, et al. A trial of imaging selection and endovascular treatment for ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(10):914-923.

- Ciccone A, Valvassori L, Nichelatti M, et al. Endovascular treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2013;368(10):904-913.

- Broderick JP, Palesch YY, Demchuk AM, et al. Endovascular therapy after intravenous t-PA versus t-PA alone for stroke. N Engl J Med 2013;368(10):893-903.

- Berkhemer OA, Fransen PS, Beumer D, et al. A randomized trial of intraarterial treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2015;372(1):11-20.

- Goyal M, Demchuk AM, Menon BK, et al. Randomized assessment of rapid endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1019-1030.

- Campbell BC, Mitchell PJ, Kleinig TJ, et al. Endovascular therapy for ischemic stroke with perfusion-imaging selection. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(11):1009-1018.

- Saver J, Goyal M, Bonafe A, et al. Solitaire FR with the intention for thrombectomy as primary endovascular treatment for acute ischemic stroke. American Heart Association International Stroke Congress, Feb 2015; Nashville, Tenn.

- Paciaroni M, Inzitari D, Agnelli G, et al. Intravenous thrombolysis or endovascular therapy for acute ischemic stroke associated with cervical internal carotid artery occlusion: the ICARO-3 study. J Neurol. 2015;262(2):459-468.

Pages: 1 2 | Multi-Page

ACEP Now features one article each issue related to an ACEP eCME CME activity.

ACEP Now features one article each issue related to an ACEP eCME CME activity.

5 Responses to “Endovascular Intervention for Stroke May Become Alternative to tPA”

May 24, 2015

Arno Vosk, MD, FACEPWe all hope this treatment really works. With practically all such things, though, the evidence supporting it comes from sources with a vested interest. The author seems aware of this.

Unanswered questions that occur to me right away: What are long-term results? Where does skill of the operator factor in? What exactly are criteria for patients who might benefit?

We are all desperate for a treatment for stroke that works, but this desperation should not cloud our judgement, or make us overeager to espouse new treatments that might not actually work well, or might not be safe. Alas, most of the information in situations like this comes from tainted sources.

May 24, 2015

Edward JauchIn the title the author misses the point of the trials referenced. The recent trials have largely compared IV to IV + endovascular thrombectomy. IV tPA will remain recommended as first line therapy and IA approaches recommended for those who meet criteria largely used in the recent stent-retriever studies, typically after receiving IV tPA. IA should not be considered as an alternative for IV tPA.

May 26, 2015

Ryan RadeckiHi Edward –

I’m afraid the editors have mis-titled my submission – I agree with your statement the trials did not evaluate IA intervention as an alternative to IV tPA. Upcoming trials appear to be addressing such a hypothesis, but the current trials are largely IA + IV tPA. The title given to the online version here makes such an allusion not referenced anywhere in the body of my article.

– Ryan

May 24, 2015

Edward JauchBy the way, among the inaccuracies in the blog, the picture is cool but demonstrates coiling an aneurysm and not related to treating an acute ischemic stroke.

June 1, 2015

Stroke DocRe: IV tpa:

“In the largest meta-analysis of angiographically confirmed intracranial occlusions, sustained early recanalization was achieved with tPA only 46.2 percent of the time.1 Comparing this with the observed 24.1 percent spontaneous recanalization rate, tPA clearly has a maximal ceiling for benefit if only one in five additional patients achieved reperfusion.”

“Because one of the best-kept secrets about tPA, the “clot buster,” is that it doesn’t bust clots” is a strange way to begin the preceding paragraph. By your own admission tPA does bust clots, 46.2% over 24.1%, which is actually an impressive difference, although certainly less than what we want.

Points raised about premature stopping of trials may well be good ones, but with now 5 positive (MRCLEAN, ESCAPE, EXTEND-IA, SWIFT-PRIME, REVASCAT) endovascular trials I don’t think it is possible to doubt that acute recanalization is a good idea in ischemic stroke in appropriate patents…and in fact these results actually reinforce my faith in tpa (and its positive Lancet/Cochrane meta-analyses of use < 4.5 hrs), as tpa does the same thing as a stent retriever, just (notably) not as well. (But still better than placebo, with no change in death rate at 3 months.)

I completely agree, however, that we could have resolved the whole tpa controversy a long time ago (including adequate patient subset analysis, which Dr. Radecki has appropriately stressed in previous posts) if someone had repeated NINDS on much larger samples a long time ago. If only.

Two final points…

1) What "recanalization" really comes to clinically depends on several factors – e.g. which artery, what degree of opening (TICI score), when the artery was opened, and what the state of surrounding brain is. As a simple example, the recanalization rate of a proximal MCA occlusion is less than that of an M2. Also, longer clots seem to recanalize more poorly. Note that among the 5 trials better and quicker degree of opening appeared to correlate with better outcomes (weaker results on REVASCAT and MRCLEAN – compare time and TICI 2b/3 recanalization data.)

2) Though the "time is brain" hypothesis has been doubted, it is supported by successive DWI imaging data, and more importantly it must be true in some way for a good number of patients, unless you are willing to believe that the endovascular trials would have produced the same results if the interventionalists had tried to open the relevant arteries the next day instead of within a few hours.

I would like to thank Dr Radecki for his thoughtfulness and non-inflammatory tone…often lacking in these discussions.