The ACEP Clinical Policies Committee regularly reviews guidelines published by other organizations and professional societies. Periodically, new guidelines are identified on topics with particular relevance to the clinical practice of emergency medicine. This article highlights recommendations for evaluation of blunt renal trauma published by the European Association of Urology in 2014.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 34 – No 11 – November 2015In 2014, the European Association of Urology published its “Guidelines on Urological Trauma.”1 The guidelines are quite expansive and offer recommendations on management of renal, ureteral, bladder, urethral, and genital trauma. In this article, I will highlight the recommendations on renal trauma that are applicable to emergency physicians.

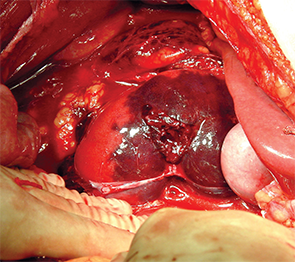

Renal fracture: intraoperative

PHOTOs: Diku P. Mandavia

These guidelines are based on a relevant literature review of several databases including MEDLINE, Embase, and Cochrane. The authors point out that most of the findings and recommendations are based on case reports and retrospective case series and recognize that the paucity of high-quality randomized controlled trials makes it difficult to make compelling recommendations. The European Association of Urology uses a grade A through C recommendation paradigm. Grade A recommendations are based on good-quality and consistent studies, including at least one randomized trial. Grade B recommendations are based on well-conducted clinical studies without randomized clinical studies. Lastly, Grade C recommendations are made without directly applicable clinical studies of good quality.

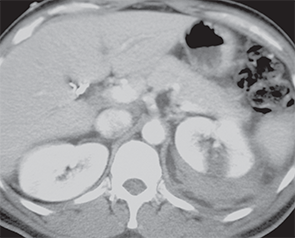

CT of a left renal fracture

PHOTOs: Diku P. Mandavia

However, there is a big caveat to this paradigm. As the guidelines state, “Alternatively, absence of high level of evidence does not necessarily preclude a grade A recommendation, if there is overwhelming clinical experience and consensus.”1 The authors denote this recommendation grade by labeling such recommendations as A*.

Epidemiology

Renal trauma occurs in approximately 1–5 percent of all trauma cases, with a 3:1 male-to-female ratio, and in all ages of patients. Blunt trauma is the leading cause of injury, with motor vehicle accidents accounting for nearly half of those injuries and falls, sports, and assaults reported as the mechanism for the majority of the remaining blunt trauma. Penetrating renal trauma from gunshot wounds and stabbings is not common but tends to be more severe and less predictable.

Blunt trauma to the back, flank, lower thorax, or upper abdomen—particularly with associated hematuria, ecchymosis, flank pain, abrasions, fractured ribs, or other signs of trauma—should raise suspicion of renal injury.

Grade A*: Findings on physical examination, such as haematuria, flank pain, flank abrasions and bruising ecchymoses, fractured ribs, abdominal tenderness, distension, or mass, could indicate possible renal involvement.1

It should be emphasized that patients with a preexisting solitary kidney are at especially high risk of renal failure because injury to the single kidney may result in substantially reduced renal function.

Labs and Imaging

All patients with suspected or confirmed renal trauma should have a baseline creatinine measurement. In animal studies, serum creatinine was noted to remain normal for eight hours after bilateral nephrectomy. Therefore, most initial creatinine levels will reflect preexisting renal disease rather than new dysfunction caused by the trauma.

A urine sample should be inspected for both gross and microscopic hematuria, although this may not be a reliable indicator of trauma. One study demonstrated up to 9 percent of cases without hematuria were associated with major injury such as disruption of the ureteropelvic junction, pedicle injuries, and segmental arterial thrombosis.

Grade A: Urine from a patient with suspected renal injury should be inspected for haematuria (visually and by dipstick analysis).

Grade C: Creatinine levels should be measured to identify patients with impaired renal function prior to injury.1

Although ultrasound can be used to identify lacerations and perinephric hematomas, computed tomography (CT) scans are more sensitive and specific. Angiography offers the added benefit of therapeutic embolization but is typically only used when there is a known injury with potential for hemostasis.

CT with intravenous contrast is necessary to assess for pedicle injury, which is indicated by a lack of contrast enhancement. If suspicion of pedicle injury is high or there are associated signs of injury, for example, hematoma or free fluid, delayed CT scans should be performed 10 to 15 minutes after contrast injection to assess for collecting-system injury that can be missed using a routine CT imaging protocol.

Grade A*: Blunt trauma patients with visible (gross) or non-visible haematuria and haemodynamic instability should undergo radiographic evaluation.

Grade B: Immediate imaging is recommended for all patients with a history of rapid deceleration injury and/or significant associated injuries.

Grade A*: All patients with or without haematuria after penetrating abdominal or lower thoracic injury require urgent renal imaging.

Grade C: Ultrasound alone should not be used to set the diagnosis of renal injury since it cannot provide sufficient information. However, it can be informative during the primary evaluation of polytrauma patients and for the follow-up of recuperating patients.

Grade A: A CT scan with enhancement of intravenous contrast material and delayed images is the gold standard for the diagnosis and staging of renal injuries in haemodynamically stable patients.1

Overall, the “Guidelines on Urological Trauma” from the European Association of Urology offer a nice review and interpretation of the current literature. The key take-home points are:

- Suspect renal injury in the presence of blunt trauma or evidence of injury near the patient’s flank along with gross or microscopic hematuria.

- CT is recommended as the initial imaging modality if kidney injury is suspected.

An initial creatinine elevation is more likely to represent preexisting renal function impairment rather than indicate acute kidney injury caused by the accident.

Dr. Pierce is a new attending at St. Thomas Rutherford Hospital in Murfreesboro, Tennessee. He wrote this article as the 2014–2015 EMRA representative to the ACEP Clinical Policies Committee while finishing residency at the University of Virginia.

Reference

- Summerton DJ, Djakovic N, Kitrey N, et al. Guidelines on urological trauma. European Association of Urology; Arnhem, The Netherlands: 2014. Accessed Aug. 5, 2015.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “European Association of Urology Guidelines for Evaluating, Managing Blunt Renal Trauma”