Diplopia, colloquially referred to as “double vision,” is a challenging chief complaint in the emergency department. The etiologies are vast. Acute life-threatening causes include stroke, aneurysm, or increased intracranial pressure. Less urgent chronic causes can include decompensated phoria (ie, misalignment of the eyes) or slowly evolving microvascular disease. Life- and organ-threatening causes should be the top concern in the emergency department, and emergency physicians must be prepared to identify any related conditions.1

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 40 – No 07 – July 2021Clinicians must first determine whether the patient has monocular or binocular diplopia. Monocular diplopia is confirmed when covering the opposite eye fails to resolve the diplopia. This strongly suggests etiologies that are nonemergent but should be referred for outpatient ophthalmologic evaluation. (Note: Some exceptions such as multiple sclerosis, seizures, or various forms of encephalopathy will be apparent by other aspects of the patient’s presentation.)2 The remainder of this article discusses binocular diplopia (henceforth referred to as diplopia), which occurs due to misalignment of the visual axes.

Neuroanatomy

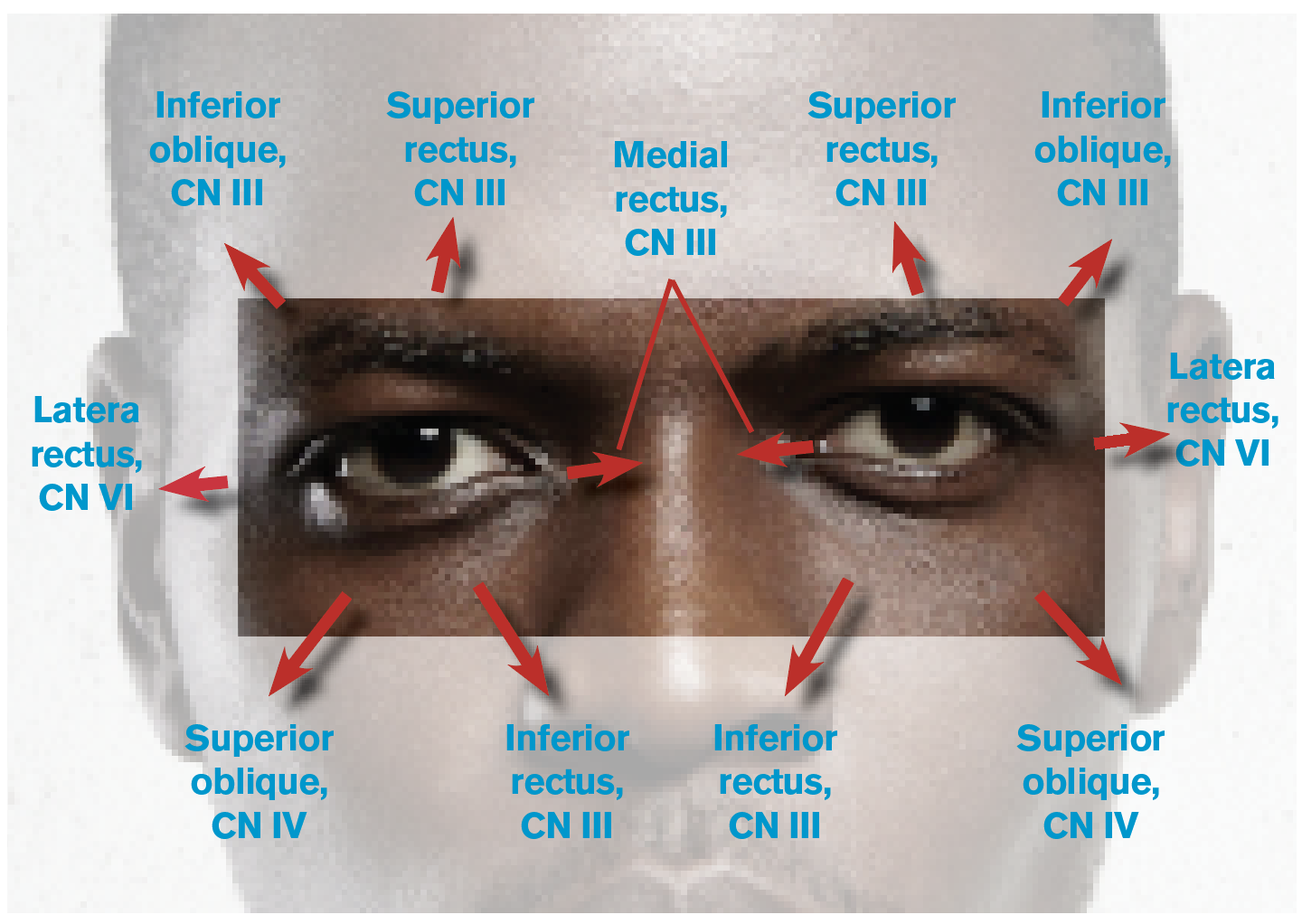

A brief review of the neuroanatomy of eye movement is helpful to recognize patterns of extraocular muscle weakness, identify cranial nerve (CN) palsies, and localize structural lesions. Proper eye alignment and movement depend on extraocular muscles innervated by CNs III, IV, and VI (see Table 1 and Figure 1). These CNs originate in the midbrain and pons, course through the subarachnoid space near important structures such as the posterior communicating artery, travel through the cavernous sinus, enter the orbit through the superior orbital fissure, and finally innervate their target extraocular muscle(s) at the neuromuscular junction. Pathology at any of these locations may cause diplopia.

A complete CN III palsy impairs eye supraduction (vertical upward glance), infraduction (vertical downward glance), and adduction. This causes the eye to rest in a “down and out” position. An incomplete CN III palsy will present with varying degrees of weakness in each of the affected extraocular muscles. Additionally, CN III contains motor fibers that control the levator muscle of the eyelid and parasympathetic fibers located on the periphery of the nerve trunk that control pupil constriction. Compressive lesions such as aneurysms will usually (but not always) result in pupil dilation with some degree of oculomotor dysfunction and/or ptosis.

Figure 1: Eye Movements and the Related Cranial Nerves (CNs) and Extraocular Muscles

CN IV palsy causes upward deviation and rotational misalignment; however, this can be difficult to identify due to the compensatory effect of other intact extraocular muscles. To diagnose an isolated unilateral CN IV palsy, the examiner should assess whether the upward deviation in the affected eye worsens with gaze toward the contralateral side and with the head tilted toward the ipsilateral side. If the exam is not consistent with these findings, one should consider alternative diagnoses.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Single Page

One Response to “How to Evaluate Diplopia and Spot Life-Threatening Etiologies”

August 11, 2025

Leonidas RojasIn the article presented, the image is incorrect, as it depicts the fourth cranial nerve as enabling abduction and downward gaze (via the superior oblique muscle), when in fact it is responsible for adduction and downward gaze (as if focusing on the tip of the nose). Regards.