Explore This Issue

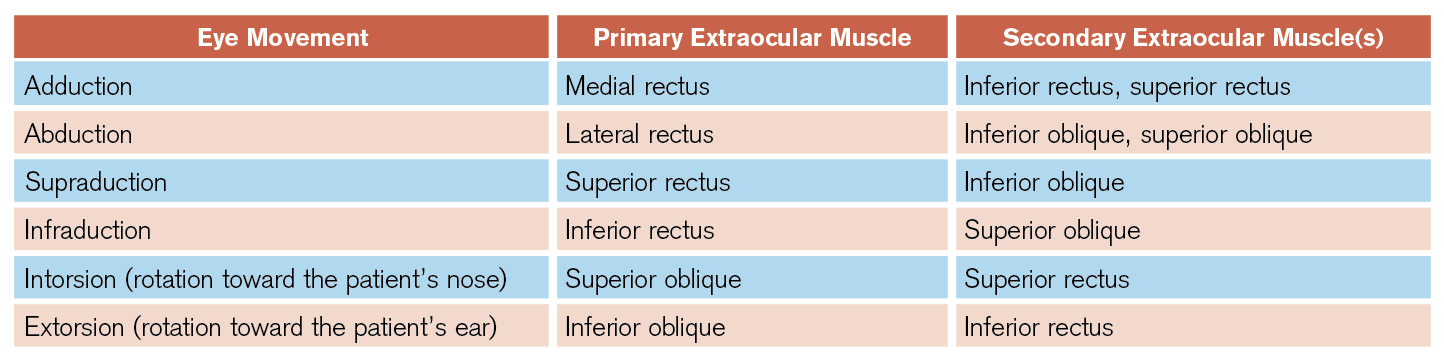

ACEP Now: Vol 40 – No 07 – July 2021(click for larger image) Table 1: Eye Movements and Corresponding Extraocular Muscles

CN VI palsy is easier to identify: Patients present with medial deviation most apparent when looking toward the affected side. It is important to note that CN VI is particularly susceptible to traction caused by structural lesions or elevated intracranial pressure, a cause particularly suggested by the presence of a bilateral CN VI palsy.

Considerations for the History and Exam

Emergency physicians must first determine whether the patient has isolated diplopia or diplopia with additional neurological deficits suggestive of a posterior circulation stroke. Patients presenting with acute-onset diplopia in combination with altered mental status, bulbar weakness (such as difficulty with speech and swallow, facial muscle use, or emotional volatility), vertigo, or “crossed” brain stem signs (ie, ipsilateral CN deficits with contralateral limb weakness or sensory loss) should be considered to have a brain stem stroke until proven otherwise. The clinician should activate institutional stroke protocols, obtain neurology consultation, and obtain neuroimaging (including an MRI after a screening CT has been obtained) as soon as possible.

After a posterior circulation stroke has been excluded, clinicians should gather a thorough history as well as perform comprehensive neurological and eye exams. It is important to determine the orientation of the diplopia (horizontal, vertical, or oblique) and whether the diplopia worsens in a particular direction of gaze. This will help to identify the extraocular muscles and/or cranial nerves affected. The onset and timing of diplopia can also aid in diagnosis. Intermittent diplopia that worsens with fatigue and later in the day is suggestive of myasthenia gravis. Slowly progressive diplopia may suggest a compressive cause (eg, inflammatory, infectious, neoplastic, or vascular lesions), whereas intermittent diplopia may be due either to a decompensating phoria or myasthenia gravis.

Pain associated with diplopia can be seen in a variety of conditions. Pain localizing to the eye or retrobulbar region—particularly pain that worsens with eye movement—suggests pathology of the cavernous sinus, orbit, and/or extraocular muscles such as Tolosa-Hunt syndrome (a condition believed to be caused by inflammation of either the cavernous sinus or the superior orbital fissure), thyroid eye disease, infection, or malignancy. Microvascular ischemia and optic neuritis can also cause pain in a similar distribution. Diplopia accompanied by headache can occur in giant cell arteritis, cavernous sinus thrombosis, pituitary apoplexy (bleeding), intracranial aneurysm, cervical artery dissection, and a variety of other conditions. As always, severe or thunderclap headache suggests aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage, which may be associated with aneurysmal compression of cranial nerves, most commonly CN III.

However, painless diplopia does not exclude serious neurological conditions, such as aneurysms, as pain is an unreliable finding in many conditions.3 Rarely, giant cell arteritis may present with diplopia in the absence of headache or other systemic symptoms. Accordingly, all patients over the age of 55 with double vision should undergo laboratory screening with erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and complete blood count.4,5

Internuclear ophthalmoplegia (INO) is an ocular motility disorder of horizontal conjugate gaze that is important to recognize. INO occurs due to a lesion in the medial longitudinal fasciculus of the brain stem, most commonly from multiple sclerosis or ischemic stroke. When a patient with INO attempts to look away from the affected side, there is impaired ipsilateral eye adduction and nystagmus of the contralateral eye on abduction. This may occur with conjugate gaze toward one or both sides. Convergence is usually preserved.

Diplopia occurring after head trauma may be due to decompensated phoria, CN palsies due to stretch injury or skull fracture, intracranial hemorrhage, direct extraocular muscle damage, extraocular muscle entrapment due to orbital fracture, orbital compartment syndrome resulting from a retrobulbar hematoma, or carotid-cavernous fistula. A noncontrast head CT should be the first neuroimaging obtained in trauma patients presenting with diplopia.

The patient’s past medical history can also suggest potential causes for diplopia. Patients with a history of malignancy should be suspected to have diplopia due to perineural spread or lesions in the orbit or brain. Patients suffering from chronic alcoholism may develop Wernicke encephalopathy characterized by altered mental status, gait ataxia, and oculomotor dysfunction. A history of cardiovascular risk factors is supportive of microvascular ischemia or vertebrobasilar insufficiency, though the presence of cardiovascular risk factors does not exclude other important causes discussed here.4,6

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Single Page

No Responses to “How to Evaluate Diplopia and Spot Life-Threatening Etiologies”