In the May 2016 issue of Annals of Emergency Medicine, ACEP published a clinical policy focusing on fever in young children and infants.1 This is a revision of a 2003 clinical policy related to pediatric fever.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 35 – No 05 – May 2016The 2016 clinical policy can also be found on ACEP’s website, and has been submitted for abstraction on the National Guideline Clearinghouse website.

This clinical policy takes an evidence-based approach to answering four questions frequently encountered when making decisions associated with pediatric fever in the emergency department. Recommendations (Level A, B, or C) for patient management are provided based on the strength of evidence using the Clinical Policies Committee’s well-established methodology:

- Level A recommendations represent patient management principles that reflect a high degree of clinical certainty.

- Level B recommendations represent patient management principles that reflect moderate clinical certainty.

- Level C recommendations represent other patient management strategies based on Class III studies or, in the absence of any adequate published literature, based on consensus of the members of the Clinical Policies Committee.

During development, this clinical policy was reviewed and comments were received from emergency physicians; members of the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Family Physicians, and ACEP’s Pediatric Emergency Medicine Committee; and those health care providers responding to the notice of the open comment period. All responses were used to further refine and enhance this policy. However, responses did not imply endorsement of this clinical policy.

This revision of the clinical policy for well-appearing infants and children 2 months to 2 years of age (29 days to 90 days for meningitis) presenting with fever was prompted by advances in diagnostic technology, the changing epidemiology, and incidences of the various infections comprising a serious bacterial infection, along with input from ACEP members, which led to four critical questions.

Critical Questions and Recommendations

Question 1. For well-appearing immunocompetent infants and children aged 2 months to 2 years presenting with fever (>38.0°C [100.4°F]), are there clinical predictors that identify patients at risk for urinary tract infection?

Question 1. For well-appearing immunocompetent infants and children aged 2 months to 2 years presenting with fever (>38.0°C [100.4°F]), are there clinical predictors that identify patients at risk for urinary tract infection?

Patient Management Recommendations

Level A recommendations: None specified.

Level B recommendations: None specified.

Level C recommendations: Infants and children at increased risk for urinary tract infection include females younger than 12 months, uncircumcised males, nonblack race, fever duration greater than 24 hours, higher fever (≥39°C), negative test result for respiratory pathogens, and no obvious source of infection. Although the presence of a viral infection decreases the risk, no clinical feature has been shown to effectively exclude urinary tract infection. Physicians should consider urinalysis and urine culture testing to identify urinary tract infection in well-appearing infants and children aged 2 months to 2 years with a fever ≥38°C (100.4°F), especially among those at higher risk for urinary tract infection.

Question 2. For well-appearing febrile infants and children aged 2 months to 2 years undergoing urine testing, which laboratory testing method(s) should be used to diagnose urinary tract infection?

Question 2. For well-appearing febrile infants and children aged 2 months to 2 years undergoing urine testing, which laboratory testing method(s) should be used to diagnose urinary tract infection?

Patient Management Recommendations

Level A recommendations: None specified.

Level B recommendations: Physicians can use a positive test result for any one of the following to make a preliminary diagnosis of urinary tract infection in febrile patients aged 2 months to 2 years: urine leukocyte esterase, nitrites, leukocyte count, or Gram’s stain.

Level C recommendations: (1) Physicians should obtain a urine culture when starting antibiotics for the preliminary diagnosis of urinary tract infection in febrile patients aged 2 months to 2 years. (2) In febrile infants and children aged 2 months to 2 years with a negative dipstick urinalysis result in whom urinary tract infection is still suspected, obtain a urine culture.

Question 3. For well-appearing immunocompetent infants and children aged 2 months to 2 years presenting with fever (>38.0°C [100.4°F]), are there clinical predictors that identify patients at risk for pneumonia for whom a chest radiograph should be obtained?

Question 3. For well-appearing immunocompetent infants and children aged 2 months to 2 years presenting with fever (>38.0°C [100.4°F]), are there clinical predictors that identify patients at risk for pneumonia for whom a chest radiograph should be obtained?

Patient Management Recommendations

Level A recommendations: None specified.

Level B recommendations: In well-appearing immunocompetent infants and children aged 2 months to 2 years presenting with fever (≥38°C [100.4°F]) and no obvious source of infection, physicians should consider obtaining a chest radiograph for those with cough, hypoxia, rales, high fever (>39°C), fever duration greater than 48 hours, or tachycardia and tachypnea out of proportion to fever.

Level C recommendations: In well-appearing immunocompetent infants and children aged 2 months to 2 years presenting with fever (>38°C [100.4°F]) and wheezing or a high likelihood of bronchiolitis, physicians should not order a chest radiograph.

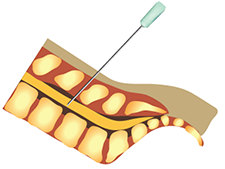

Question 4. For well-appearing immunocompetent full-term infants aged 1 month to 3 months (29 days to 90 days) presenting with fever (>38.0ºC [100.4°F]), are there predictors that identify patients at risk for meningitis from whom cerebrospinal fluid should be obtained?

Question 4. For well-appearing immunocompetent full-term infants aged 1 month to 3 months (29 days to 90 days) presenting with fever (>38.0ºC [100.4°F]), are there predictors that identify patients at risk for meningitis from whom cerebrospinal fluid should be obtained?

Patient Management Recommendations

Level A recommendations: None specified.

Level B recommendations: None specified.

Level C recommendations: (1) Although there are no predictors that adequately identify full-term well-appearing febrile infants aged 29 to 90 days from whom cerebrospinal fluid should be obtained, the performance of a lumbar puncture may still be considered. (2) In the full-term well-appearing febrile infant aged 29 to 90 days diagnosed with a viral illness, deferment of lumbar puncture is a reasonable option given the lower risk for meningitis. When lumbar puncture is deferred in the full-term well-appearing febrile infant aged 29 to 90 days, antibiotics should be withheld unless another bacterial source is identified. Admission, close follow-up with the primary care provider, or a return visit for a recheck in the ED is needed (consensus recommendation).

Fever is the most common presenting complaint of infants and children presenting to an emergency department. Fever accounts for 15 percent of all ED visits for pediatric patients younger than 15 years of age. Very young patients, particularly those younger than 3 months of age, have a somewhat immature immune system, which makes them more susceptible to infections. Most infants and children with a fever will have a benign, self-limited infection. However, a few of these febrile infants and children may have a serious, even life-threatening infection. The toxic or ill-appearing infant or child usually does not pose a diagnostic dilemma. However, not all infants and young children with a serious, life-threatening infection will appear ill or toxic. The dilemma for the health care provider is to differentiate the well-appearing febrile infant or child with a serious bacterial infection from the febrile infant or child with a benign, usually viral infection.

Fever accounts for 15 percent of all ED visits for pediatric patients younger than 15 years of age. Very young patients, particularly those younger than 3 months of age, have a somewhat immature immune system, which makes them more susceptible to infections.

In the years following the introduction of the pneumococcal vaccine and the Haemophilus influenza type b vaccines, there have been changes in the predominant bacterial pathogens and in the incidences of the various types of serious bacterial infections. The incidences of occult bacteremia, pneumococcal meningitis, and pneumococcal pneumonia have declined, while Escherichia coli has become the predominant bacterial pathogen and the leading cause of bacteremia, urinary tract infections, and bacterial meningitis in young infants. The most common serious bacterial infection is now urinary tract infection in febrile infants younger than 24 months of age, with a prevalence of 5 percent to 7 percent and higher in certain high-risk groups (eg, up to 20 percent in uncircumcised male infants). Various diagnostic technologies, including rapid antigen testing for viruses and bacteria, have been produced.

Multiple clinical decision rules have been proposed and various biological markers suggested for use in the identification of serious bacterial infection, including the white blood cell count, absolute neutrophil count, band count, C-reactive protein, interleukins, and procalcitonin. However, at present, there is no widespread acceptance of any one clinical decision rule or screening test,

Future research should focus on the changing epidemiology of serious bacterial infections, the use of diagnostic technologies, and the utility of specific biomarkers and clinical algorithms in the differentiation of infants and children with benign febrile illness from febrile infants and children with a serious bacterial infection.

Dr. Mace is professor of medicine at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University and director of research at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio.

Reference

- Mace SE, Gemme SR, Valente JH, et al. American College of Emergency Physicians. Clinical policy for well-appearing infants and children younger than 2 years of age presenting to the 2 emergency department with fever. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;67:625-639.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

ACEP Now features one article each issue related to an ACEP eCME CME activity.

ACEP Now features one article each issue related to an ACEP eCME CME activity.

No Responses to “Evaluating Fever in Well-Appearing Infants and Children”