Part 3 of a three-part series. Part 1 was published in the Nov. 2014 issue, and Part 2 was published in the Dec. 2014 issue.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 34 – No 01– January 2015Interest in practicing and teaching emergency medicine around the world has increased exponentially. Many of our colleagues now have some international experience, many others dream of following a path to remote regions, and most academic centers are considering, if not running, fellowships related to international emergency medical care.

Yet most emergency physicians are unclear how to identify and evaluate global volunteer opportunities, what to expect when they travel to remote lands, and how to prepare for their experience. This article, the last of a three-part series based on The Global Healthcare Volunteer’s Handbook: What You Need to Know Before You Go, provides some of the basic information that emergency physicians need for these ventures.

Communication Issues: An Example

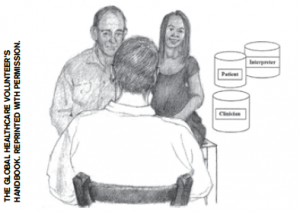

You arrived at the airport and, after a bit of confusion, got to your accommodations and found your way to the hospital, where you stepped into your role as a clinician/teacher. Your colleagues are friendly, but their English accents and vocabulary vary from what you are used to; you make do. However, although it is one of the country’s national languages, none of the patients speak English, so you’re working through makeshift interpreters, which is frustrating. A colleague helpfully suggests that you talk directly to the patient rather than to the interpreter, who should sit behind the patient (see Figure 1).1

“How about ‘zone’ for the patient?” asks the nurse. “Of course,” he continues, “we should probably give her some paracetamol and pethidine first.”

“Huh?” you weakly reply. The middle-age patient looks up at you with pleading eyes for some relief from her abdominal pain. What should you do?

Figure 1. Optimal medical interpreter positioning.

When working internationally, you expect to see unfamiliar diseases, unusual mechanisms of injury, novel medical and surgical techniques, and sparse equipment and supplies in resource-poor regions. However, you may not be ready to suddenly need to use multiple medications with which you have little or no experience or don’t immediately recognize.

“Can you show me the medications?” you ask the nurse. He hands you the three vials, and the situation becomes clear. The nurse was using a combination of local medical slang (“zone” for ceftriaxone) and the internationally more common generic names for acetaminophen (paracetamol, often called Panadol, a common brand name) and meperidine (pethidine). (See Table 1 for more commonly confused terms.) Now that you understand, he asks how much parenteral paracetamol you want to give (a common route around the globe).

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

One Response to “What to Expect at Your Global Health Care Volunteer Destination”

April 28, 2015

EricaTherefore the dental implant, slight discomfort can be relieved with over-the-table pain medicines, for example Tylenol or Motrin.