From 2002 to 2017, there has been more than a fourfold increase in the total number of opioid-related deaths, with more than a sevenfold increase in heroin overdose deaths and a 22-fold increase in synthetic opioid overdose deaths in the United States.1 Hospital billing data from 2014 suggest that more than 90,000 emergency department patients presented with visits for unintentional, nonfatal opioid overdoses.2 And the prevalence of suspected opioid overdose–related ED visits has significantly increased recently as well.3

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 38 – No 01 – January 2019Why does this matter to emergency physicians?

Because ED visits related to opioid use provide the perfect opportunity to start patients on treatment and kick-start their path to recovery. Many of these patients have no other access to health care, and patients are more likely to become opioid-free when treated and counseled appropriately after an opioid-related illness.

And along with the recent trends in opioid-related deaths, we’ve seen a parallel development in improved care of patients with the use of the partial opioid agonist buprenorphine-naloxone. This treatment modality has only recently been studied in emergency departments, and evidence suggests buprenorphine-naloxone decreases mortality, improves withdrawal symptoms, decreases drug use, improves follow-up rates, and decreases crime rates.4–7 Therefore, it is now more important than ever that all emergency medicine providers take on the responsibility of learning about this lifesaving medication and implement it in their practices.

Recognizing Opioid Withdrawal

The clinical features of opioid withdrawal overlap with severe gastroenteritis—symptoms include crampy abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, muscle aches, chills, and diaphoresis—making it easy to confuse the two. Opioid withdrawal’s distinguishing features include watery eyes and nose, severe insomnia, gooseflesh, mydriasis, anxiety, restlessness, tachycardia, and hypertension.

Opioid withdrawal is rarely life-threatening. However, it may precipitate preterm labor in pregnant patients and acute coronary syndrome in patients with coronary artery disease, and there are published case reports of temporally-related Takotsubo cardiomyopathy.8

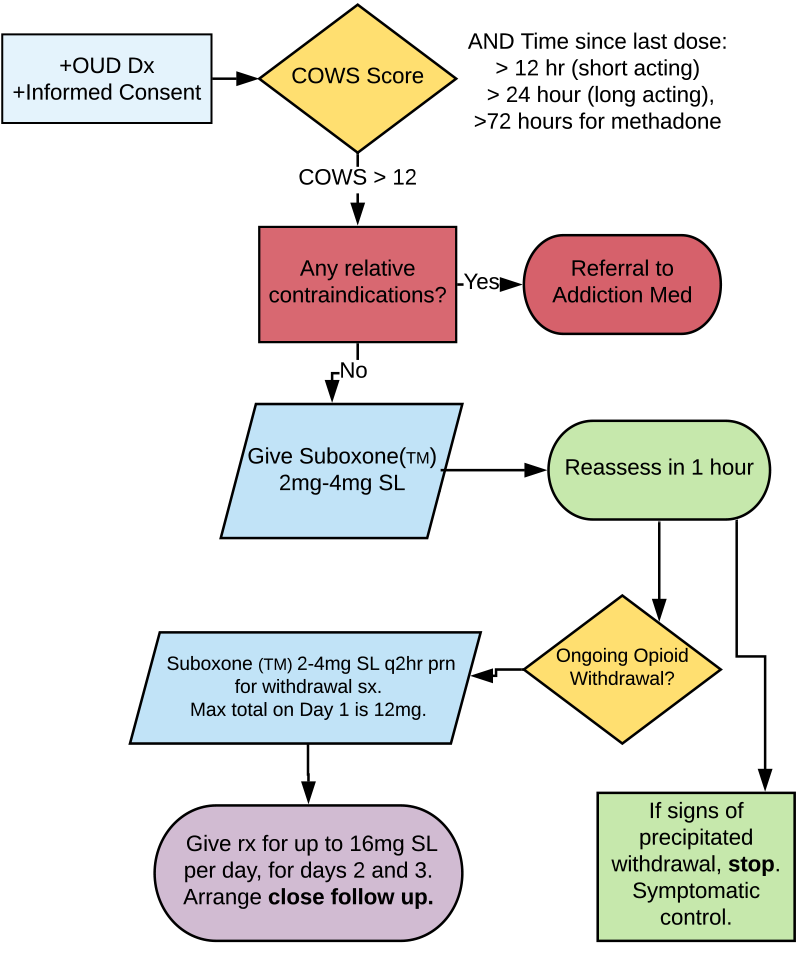

The various opioids feature a wide range of half-lives, ranging from a few hours with fentanyl to several days with methadone. Even after just five days of taking an opioid, physical and psychological withdrawal symptoms may develop upon cessation. Consider these five steps when prescribing opioids from the emergency department, and counsel patients appropriately (see Figure 1 for a flowchart of this process).

(click for larger image) Figure 1: Assessing and Treating Opioid Withdrawal & Opioid Use Disorder

OUD = opioid use disorder; COWS = clinical opioid withdrawal scale.

Credit: Taryn Lloyd

Step 1: Does the Patient Meet Criteria for Opioid Use Disorder?

Patients must meet at least two of the following criteria in a 12-month period to meet the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) criteria for opioid use disorder.9

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Single Page

No Responses to “Five Steps to Help You Manage Opioid Use Disorder Patients”