If you provide direct patient care in a hospital setting, you no doubt have great familiarity with systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). As quality measures relating to sepsis care have proliferated, along with public reporting and reimbursement tie-ins, hospitals have taken notice. As sepsis quality measures generally include requirements for timely interventions, hospitals have been vigorously implementing tools intended for the early detection of sepsis. These tools ubiquitously take the form of pernicious alerts and interruptions embedded in the electronic medical record (EMR).

Owing to its great familiarity, regrettably, SIRS is the basis for the vast majority of these tools.

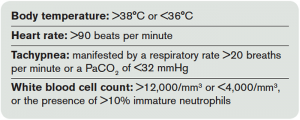

Formally codified in 1992 by the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the American College of Chest Physicians, the definition of SIRS incorporates four types of criteria (see Table 1).1 Based on physiologic and laboratory measures meant to reflect the derangements caused by infection, these criteria attempt to objectively define the effects of stress on the body. This concept was introduced and formalized as part of our contemporary definitions for the spectrum of infection and organ dysfunction, including sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic shock. At the time of introduction, it was made explicitly clear by the authors that SIRS resulted from many clinical conditions beyond infection: pancreatitis, ischemia, multiple trauma, immune-mediated injury, and other exogenous factors.

However, an appreciation for such diverse causes of SIRS seems to have been lost since these authors’ penned their definition, and SIRS has become cognitively associated almost exclusively with sepsis alone. As a result, institutional tools for detecting sepsis are based primarily on this foundation.

One of these alerts, created by the Cerner Corporation, is described in a recent publication in the American Journal of Medical Quality.2 Its cloud-based system analyzes patient data in real-time as it enters the EMR and matches the data against the SIRS criteria. Based on 6,200 hospitalizations retrospectively reviewed, the alert fired for 817 patients (13 percent) meeting two or more SIRS criteria. Of these, 622 (76 percent) were either superfluous or erroneous, with the alert occurring either after the clinician had ordered antibiotics or in patients for whom no infection was suspected or treated. Of the remaining alerts occurring prior to action to treat or diagnose infection, most (89 percent) occurred in the emergency department, and a substantial number (34 percent) were erroneous.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

No Responses to “Focus on Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome Can Interfere With Early Sepsis Detection”