If you provide direct patient care in a hospital setting, you no doubt have great familiarity with systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). As quality measures relating to sepsis care have proliferated, along with public reporting and reimbursement tie-ins, hospitals have taken notice. As sepsis quality measures generally include requirements for timely interventions, hospitals have been vigorously implementing tools intended for the early detection of sepsis. These tools ubiquitously take the form of pernicious alerts and interruptions embedded in the electronic medical record (EMR).

Owing to its great familiarity, regrettably, SIRS is the basis for the vast majority of these tools.

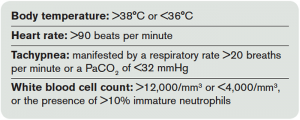

Formally codified in 1992 by the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the American College of Chest Physicians, the definition of SIRS incorporates four types of criteria (see Table 1).1 Based on physiologic and laboratory measures meant to reflect the derangements caused by infection, these criteria attempt to objectively define the effects of stress on the body. This concept was introduced and formalized as part of our contemporary definitions for the spectrum of infection and organ dysfunction, including sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic shock. At the time of introduction, it was made explicitly clear by the authors that SIRS resulted from many clinical conditions beyond infection: pancreatitis, ischemia, multiple trauma, immune-mediated injury, and other exogenous factors.

However, an appreciation for such diverse causes of SIRS seems to have been lost since these authors’ penned their definition, and SIRS has become cognitively associated almost exclusively with sepsis alone. As a result, institutional tools for detecting sepsis are based primarily on this foundation.

One of these alerts, created by the Cerner Corporation, is described in a recent publication in the American Journal of Medical Quality.2 Its cloud-based system analyzes patient data in real-time as it enters the EMR and matches the data against the SIRS criteria. Based on 6,200 hospitalizations retrospectively reviewed, the alert fired for 817 patients (13 percent) meeting two or more SIRS criteria. Of these, 622 (76 percent) were either superfluous or erroneous, with the alert occurring either after the clinician had ordered antibiotics or in patients for whom no infection was suspected or treated. Of the remaining alerts occurring prior to action to treat or diagnose infection, most (89 percent) occurred in the emergency department, and a substantial number (34 percent) were erroneous.

Therefore, based on the presented data, 126 of 817 SIRS alerts (15 percent) provided accurate, potentially valuable information. Unfortunately, another 80 patients in the hospitalized cohort received discharge diagnoses of sepsis despite never triggering the tool. Finally, these data only describe patients requiring hospitalization and not those discharged from the emergency department. We can only speculate regarding the number of alerts triggered on the diverse ED population not requiring hospitalization, as prior work has estimated infection constitutes no more than a quarter of patients with SIRS in the emergency department.3 If such estimates hold true, the potential utility of such a SIRS-based tool drops below 5 percent.

The lead author proudly concludes their tool is “an effective approach toward early recognition of sepsis in a hospital setting.” Of course, the author, employed by Cerner, also declares he has no potential conflicts of interest regarding the publication in question.

Now, for a serious condition such as severe sepsis, it is reasonable to accept some limitations in specificity in the interests of maximal sensitivity. But the Cerner tool is simply an early warning tool for sepsis, the less critically important cousin of severe sepsis. Fewer than half of the alerts produced by the Cerner tool were for instances detecting severe sepsis, the condition targeted for immediate interventions pioneered by early goal-directed therapy and its cousins. These are the cases for which we suffer alert fatigue, and yet, as a recent New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) article further describes, these criteria will still miss one in eight patients with significant mortality risk.4

These authors of the NEJM article retrospectively reviewed 13 years of patient data from 172 intensive care units in New Zealand and Australia. After identifying those patients with organ failure (eg, severe sepsis), they categorized them by the number of manifested SIRS criteria. They found that even in ICU patients with an infection and organ dysfunction, nearly 12 percent met zero or one SIRS criteria. That is to say, even in a critically ill population of which 42 percent exhibited septic shock, a SIRS-based tool, such as the Cerner instrument, would not be triggered one out of eight times.

Even worse for the SIRS criteria, these authors found the traditional threshold of two or more conferred minimal prognostic value. Patients with zero or one SIRS criteria had a combined 16.1 percent risk of in-hospital death. Those with SIRS-positive sepsis had 24.5 percent in-hospital mortality, but the adjusted odds of death were statistically no different between those with zero or one SIRS criteria and those with two or three SIRS criteria.

Simply put, the arbitrary cutoff of two or more features to declare SIRS positive is not supported by the evidence. These authors summarize their findings in perfect harsh clarity: “Our findings challenge the sensitivity, face validity, and construct validity of the rule regarding two or more SIRS criteria in diagnosing or defining severe sepsis.”

Thus, neither does SIRS equate with sepsis, nor do all patients with severe sepsis manifest SIRS. Yet our practice is governed by tools subjecting us to cognitive bludgeoning based on these criteria. This is a sad convergence of distracting, ineffective, and inefficient medicine, and we ought collectively to resist such efforts. The consequences of such “quality”-driven initiatives are clear: distractions, overdiagnosis, and waste. Early detection of sepsis absolutely has value, but we should demand we are provided with better tools.

References

- Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 1992;101:1644-1655.

- Amland RC, Hahn-Cover KE. Clinical decision support for early recognition of sepsis. Am J Med Qual. 2014 Nov 10. [ePub ahead of print]

- Horeczko T, Green JP, Panacek EA. Epidemiology of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2014;15:329-336.

- Kaukonen KM, Bailey M, Pilcher D, et al. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria in defining severe sepsis. NEJM. 2015;372:1629-1638.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “Focus on Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome Can Interfere With Early Sepsis Detection”