However, unlike with chest pain, there are far fewer industry partners performing research tied to marketing new imaging technology or diagnostic assays. The net result is an even more disappointing spectrum of recommendations than in GRACE-1. For example, addressing the common question regarding the necessity of repeat CT scanning in this “low-risk” population, the authors could not find any relevant evidence, and were therefore unable to formulate any recommendation regarding imaging avoidance on a subsequent visit. The authors did make conditional recommendations based on “very low certainty of evidence” regarding avoidance of ultrasound following a normal CT scan, and, as in recurrent chest pain, consideration of depression or anxiety screening for patients with intractable recidivism. In spite of lack of evidence, the authors make a very reasonable recommendation of good clinical practice to avoid treating with opiates when feasible.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 42 – No 08 – August 2023The third, GRACE-3, garnered a greater measure of controversy. These guidelines address the approach to acute dizziness and vertigo in the ED; they diverge from the preceding two guidelines. The most striking difference is the number of recommendations, 14, published along with several bespoke, companion, systematic reviews informing the recommendations. GRACE-3 also includes substantially more educational content relevant to the approach to acute dizziness in the ED, breaking down the important diagnoses and their clinical features. There is, finally, dramatically better evidence informing these guidelines, with several recommendations carrying “high certainty of evidence.”

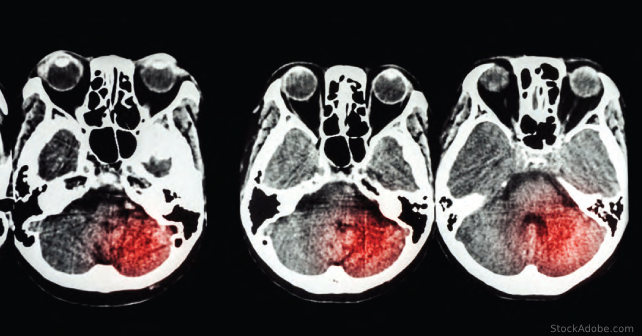

Those recommendations with “high certainty” pertain primarily to the use of advanced imaging in the diagnostic approach to acute dizziness. Importantly, these authors strongly recommend against the use of either non-contrast CT or CT angiography of the brain to distinguish between a central or peripheral cause for dizziness. Due to its wide availability and accessibility in most EDs, the allure of ordering a CT in the context of possible intracerebral pathology runs high. However, fewer than one percent of patients with dizziness will have a cause identified on CT, virtually all of whom have additional neurologic findings. The consideration to use CT for exclusion of intracranial hemorrhage is noted to be unfounded, as patients with intracranial hemorrhage do not typically present with complaints of isolated vertigo or dizziness.

Many of the other recommendations, however, are enmeshed with the primary controversial issue in this guideline. The core element of the guideline is promotion of the head impulse, nystagmus, and test of skew (HINTS) examination. There is high certainty of evidence that clinicians trained in the HINTS examination are able to distinguish between central and peripheral causes of dizziness. Unfortunately, the training element is key, as there is ample evidence that clinicians who have not undertaken any special training are not able to apply HINTS correctly. Therefore, the authors of GRACE-3 call for wide training of the EM workforce in the use of HINTS.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

No Responses to “Gradually Circling Around the GRACE Project’s “Reasonable Practice””