Case Presentation

A 28-year-old man is brought to the emergency department (ED) by his partner. He regularly drinks alcohol and has a history of depression but stopped taking his medications a month ago. He told his partner he was going to hang himself with a rope or belt and has threatened suicide in the past. Upon arrival, the patient appears inebriated and emotional. As you examine him, he becomes agitated and attempts to strike the nurse and leave the emergency department.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 41 – No 05 – May 2022You notify hospital security to help subdue the patient and treat him with intramuscular haloperidol and lorazepam. Vital signs are temperature 98.8 degrees F, blood pressure 130/84, pulse 102, respiratory rate 18 and oxygen saturation 98 percent on room air. His electrocardiogram (ECG), liver function tests and other labs are normal. Toxicology screen is positive for cannabinoids, benzodiazepines, and serum ethyl alcohol (EtOH) is 281 mg/dL. The county’s hospital psychiatric consultation service agrees to see the patient after waiting for his EtOH level to diminish. In speaking with the patient, the psychiatric assessor determines that he has access to lethal means of harm, including firearms at home. She initiates a psychiatric hold, which you sign, and attempts to place the patient in a psychiatric inpatient unit; no beds are available currently, but one is expected to open soon. The patient’s financial status precludes private psychiatric hospital admission. After 30 hours in your emergency department, the patient becomes restless. He wants to go out to smoke and demands to leave. His nurse asks, “Can we just sign him out against medical advice so he can go have his cigarette?”

Decisional Capacity and Informed Consent

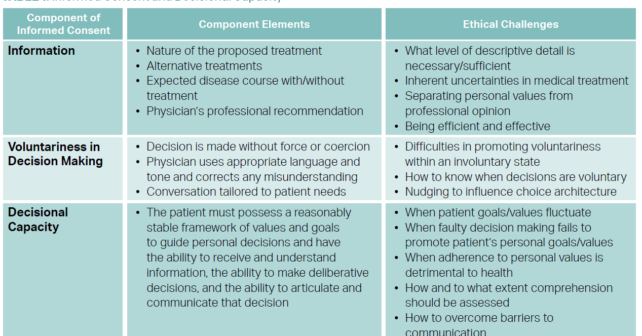

Decisional capacity requires (1) the ability of the patient to understand the information relevant to the medical decision at hand, including reasonable alternatives and no treatment; (2) the ability to evaluate the consequences and make a decision consistent with the patient’s own goals and values; and (3) the ability to communicate the decision.1 This may be determined using the Aid to Capacity Evaluation (ACE).2

Seeking and obtaining informed consent for, or refusal of, treatment is a routine part of the physician-patient interaction. In 1914, Supreme Court Justice Benjamin Cardozo stated that “[e]very human being of adult years and sound mind has a right to determine what shall be done with his own body.”3 In the second half of the 20th century, court rulings asserted that patient consent to treatment must be “informed”—that is, it must be based on provision of information to patients about their diagnoses, the nature of the proposed treatments, the potential risks (common and severe) of those treatments, alternative treatments and the expected disease course in the absence of treatment.4 Despite legal and ethical guidance, cultural, social, educational, health, and mental status factors pose ongoing challenges in understanding and honoring patient rights to informed consent.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

No Responses to “How to Approach Psych Patients Who Refuse Treatment in the Emergency Department”