Case Presentation

A 28-year-old man is brought to the emergency department (ED) by his partner. He regularly drinks alcohol and has a history of depression but stopped taking his medications a month ago. He told his partner he was going to hang himself with a rope or belt and has threatened suicide in the past. Upon arrival, the patient appears inebriated and emotional. As you examine him, he becomes agitated and attempts to strike the nurse and leave the emergency department.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 41 – No 05 – May 2022You notify hospital security to help subdue the patient and treat him with intramuscular haloperidol and lorazepam. Vital signs are temperature 98.8 degrees F, blood pressure 130/84, pulse 102, respiratory rate 18 and oxygen saturation 98 percent on room air. His electrocardiogram (ECG), liver function tests and other labs are normal. Toxicology screen is positive for cannabinoids, benzodiazepines, and serum ethyl alcohol (EtOH) is 281 mg/dL. The county’s hospital psychiatric consultation service agrees to see the patient after waiting for his EtOH level to diminish. In speaking with the patient, the psychiatric assessor determines that he has access to lethal means of harm, including firearms at home. She initiates a psychiatric hold, which you sign, and attempts to place the patient in a psychiatric inpatient unit; no beds are available currently, but one is expected to open soon. The patient’s financial status precludes private psychiatric hospital admission. After 30 hours in your emergency department, the patient becomes restless. He wants to go out to smoke and demands to leave. His nurse asks, “Can we just sign him out against medical advice so he can go have his cigarette?”

Decisional Capacity and Informed Consent

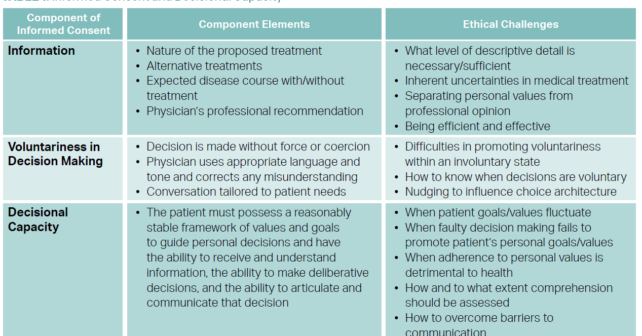

Decisional capacity requires (1) the ability of the patient to understand the information relevant to the medical decision at hand, including reasonable alternatives and no treatment; (2) the ability to evaluate the consequences and make a decision consistent with the patient’s own goals and values; and (3) the ability to communicate the decision.1 This may be determined using the Aid to Capacity Evaluation (ACE).2

Seeking and obtaining informed consent for, or refusal of, treatment is a routine part of the physician-patient interaction. In 1914, Supreme Court Justice Benjamin Cardozo stated that “[e]very human being of adult years and sound mind has a right to determine what shall be done with his own body.”3 In the second half of the 20th century, court rulings asserted that patient consent to treatment must be “informed”—that is, it must be based on provision of information to patients about their diagnoses, the nature of the proposed treatments, the potential risks (common and severe) of those treatments, alternative treatments and the expected disease course in the absence of treatment.4 Despite legal and ethical guidance, cultural, social, educational, health, and mental status factors pose ongoing challenges in understanding and honoring patient rights to informed consent.

Refusal of Treatment

Intoxication

There is broad consensus that intoxicated patients lack decisional capacity and therefore do not have the ability to consent to or refuse treatment. There is, however, a lack of consensus about what constitutes intoxication or what level of decision making about one’s health is affected by intoxication. Many psychiatrists request medical screening necessitating a serum EtOH less than 80 mg/dL or 100 mg/dL for admission, though many emergency physicians think that the determination of intoxication is a clinical one. Intoxicated patients, regardless of how this is defined, may not refuse life-sustaining treatment, such as a mental health evaluation, but may refuse interventions without life-threatening consequences, such as sutures placed for cosmesis.

Psychiatric Emergency

The original court ruling in the Massachusetts case Rogers v. Okin narrowly defined a psychiatric emergency as a situation that poses, “the substantial likelihood of physical harm.”5 The definition was eventually broadened to include both, “occurrence or serious threat of extreme violence, personal injury or attempted suicide” as well as the “necessity of preventing immediate, substantial and irreversible deterioration of a serious mental illness … in which even the smallest of delays would be intolerable.”6 One can see that this interpretation leaves broad scope to the judgment of the emergency physician.

Determination of Danger to Self and/or Others

To assess a patient’s risk of suicide and harm to self, emergency physicians can use validated screening tools, including ICAR2E and ED-SAFE, which consider factors such as a patient’s preexisting psychiatric illnesses, history of prior attempts, and access to lethal means.7

Tools that have been developed to screen for violent and harmful behavior toward others in both the health care and criminal justice fields have variable predictive validity, so clinical judgment is required.8,9 Emergency physicians should be wary of how implicit biases may impact their assessment of patients’ risk to self or others.

Project BETA (Best Practices in the Evaluation and Treatment of Agitation) provides consensus guidelines on managing patients with acute agitation in the emergency department and recommends a first-line approach of verbal de-escalation and identifying and treating contributing underlying or psychiatric conditions.10 Physical restraints should always be a last resort. Further, physicians should not use pharmacological tools with the goal of sedating patients long term. Finally, if a patient is believed to pose a reasonable threat to an identifiable target, observance of the Tarasoff Duty to Warn obliges physicians in most states to prioritize safety of others over patient confidentiality.11,12 The justification for this is that the benefit of mitigating foreseeable and significant harm to a third party outweighs encroachment on the patient’s confidentiality and autonomy.

Emergency Detention Statutes and Regulations

All 50 states have emergency hold laws that allow involuntary admission to a health care facility for persons with an acute mental illness that may result in danger to self or others. There is significant variation regarding the duration of the hold, who can initiate the hold, and rights of patients. Nearly all states specify rights of patients, which may include the right to phone calls, access to an attorney, right to appeal, written notification of the reason for the hold, and discharge transportation.13

Conclusion and Case Resolution

Tools for assessing capacity as well as suicide risk are available to the emergency physician. The patient described does not have the right to refuse treatment due to his acute intoxication and to the emergency physician’s determination that he poses a threat to himself or others. Every effort should be made to use verbal de-escalation techniques and patient education to intervene on the patient’s behavior. Allowing family or friends to visit may help orient and educate the patient during extended wait times for placement in a psychiatric facility. Although physical or pharmacological means of treating agitation may be employed, emergency physicians must keep in mind issues of safety for themselves and the ED staff. In this specific case outlined earlier, the physician judges that the patient continues to pose a threat to himself and medications are used to sedate him until a psychiatric transfer is possible. He is also offered a nicotine patch.

References

- Derse AR, Schiedermayer DL. Practical Ethics for Students, Interns, and Residents. 4th ed. Hagerstown, MD: University Publishing Group; 2015.

- Aid to capacity evaluation (ACE). Joint Centre for Bioethics. http://www.jcb.utoronto.ca/tools/ace_download.shtml.

- Schloendorff v Society of New York Hospital, 211 NY 125, 105 NE 92 (1914).

- Salgo v Leland Stanford Jr. University Board of Trustees, 154 Cal App 2d 560, 317 P 2d 170 (1957).

- Rogers v Okin, 478 F Supp 1342 (D Mass 1979).

- Rogers v Commissioner of Department of Mental Health, 458 NE 2d 308 (Mass 1983).

- Brenner JM, Marco CA, Kluesner NH, et al. Assessing psychiatric safety in suicidal emergency department patients. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2020;1(1):30-37.

- ACEP Public Health and Injury Prevention Committee. Risk assessment and tools for identifying patients at high risk for violence and self-harm in the ED. ACEP. 2015. https://www.acep.org/globalassets/sites/acep/media/public-health/risk-assessment-violence_selfharm.pdf.

- Singh J, Grann M, Fazel S. A comparative study of violence risk assessment tools: a systematic review and metaregression analysis of 68 studies involving 25,980 participants. Clin Psychol Review. 2011;31(3):499-513.

- Roppolo L, Klinger L, Leaf J. Hostile workplace: emergency management of the agitated patient. Crit Decis Emerg Med. 2019;33(2):3-10.

- Tarasoff v Regents of University of California, 17 Cal 3d 425, 551 P 2d 334, 131 Cal Rptr 14 (Cal 1976).

- Mental health professionals’ duty to warn. National Conference of State Legislatures. 2018. https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/mental-health-professionals-duty-to-warn.aspx.

- Hedman LC, Petrila J, Fisher WH, et al. State laws on emergency holds for mental health stabilization. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(5):529-535.

Dr. Baker is an attending emergency physician at Riverwood Emergency Services, Inc. in Perrysburg, Ohio.

Dr. Brenner is professor of emergency medicine at SUNY-Upstate Medical University in Syracuse, New York.

Dr. Chao is house officer in emergency medicine at the University of Michigan.

Dr. Derse is the Julia and David Uihlein chair in medical humanities and professor at the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Dr. Marco is professor of emergency medicine & surgery at Wright State University and ACEP Now associate editor.

Dr. Vearrier is an emergency medicine physician at the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “How to Approach Psych Patients Who Refuse Treatment in the Emergency Department”