The Case

A 23-year-old woman with no significant past medical history presents to your emergency department with one-day history of gradually worsening left lower quadrant (LLQ) abdominal pain. Her last menstrual period is unknown, as she reports she no longer has regular menstruation since having a Mirena intrauterine device (IUD) placed 18 months ago. She reports vaginal spotting a few days ago, which resolved. The pain is mild and intermittent without vomiting, diarrhea, fever, or dysuria. Her vital signs are blood pressure 108/68, heart rate 108, respiratory rate 16, oxygen saturation 99 percent, and temperature 98.7° F orally. On exam, she is tender to palpation in the LLQ.

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 38 – No 09 – September 2019Background

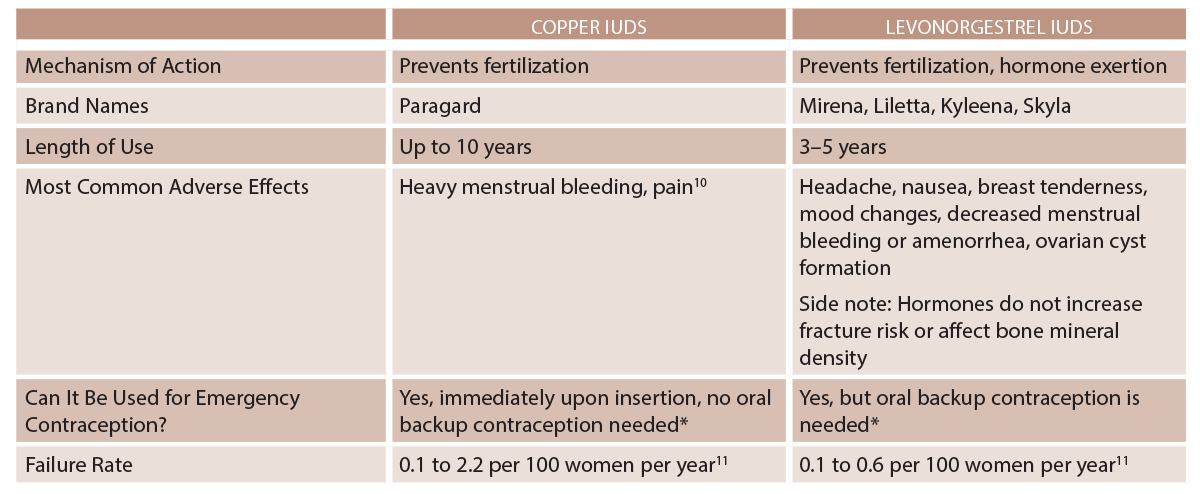

IUDs are a form of long-acting reversible contraceptive and one of the most effective reversible contraceptive methods.1 A summary of their actions and mechanisms is listed in Table 1.

Bottom line: As the popularity of IUDs has increased, the importance also increases for emergency care providers to understand the use and pathologies associated with IUDs. Given the increasing popularity of this method of contraception, we may see more IUD complications in the emergency department.2 Complications with IUDs include expulsion, method failure/unplanned pregnancy, uterine perforation, pelvic inflammatory disease, abdominal or pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, and abnormal bleeding.3

Approach to Abnormal Uterine Bleeding, Abdominal/Pelvic Pain

In addition to the above IUD-specific complications, new onset of abnormal uterine bleeding and abdominal or pelvic pain should be evaluated similarly to that of non-IUD users with the differential diagnosis including:

- Complications of pregnancy

- Pelvic inflammatory disease

- Urinary tract infection

- Intra-abdominal processes

- Ovarian cyst or torsion

- Gynecologic malignancy

Initial management of the patient with abnormal uterine bleeding should include a pelvic examination (to attempt IUD string visualization) with a possible pelvic ultrasound to assess IUD location.4

Pregnancy with an IUD

When a patient with an IUD is determined to be pregnant, the first priority is to determine the location of the pregnancy. Women who become pregnant with an IUD in place are more likely to have an ectopic pregnancy.1

Interuterine Pregnancy: Determine the woman’s desire to continue or terminate the pregnancy, gestational age, IUD location, and whether IUD strings are visible.5

For women with an IUD desiring pregnancy continuation, IUD removal is recommended. Retained IUDs have increased risk of spontaneous abortion, septic abortion, chorioamnionitis, placental abruption, placenta previa, cesarean delivery, low-birth-weight infants, and preterm delivery especially.

If the strings are visible and the IUD can be easily removed from the cervical canal, it is recommended to do so; however, if the strings have retracted into the uterus, ultrasound-guided IUD removal may be performed by a specialist but may disrupt a wanted pregnancy. Patients will need to be counseled appropriately.5,6 After IUD removal, women who conceived with an IUD in place remain at high risk for complications compared to pregnancies conceived without an IUD.6 For women desiring pregnancy termination, the IUD can be removed prior to or during a medical abortion.5

Ectopic Pregnancy: Use of an IUD does not increase the absolute risk of ectopic pregnancy because it prevents pregnancy effectively. However, if pregnancy is suspected and confirmed with an IUD in place, the pregnancy is more likely to be ectopic.5 Point-of-care ultrasound can assist with rapid, accurate diagnosis of ruptured ectopic pregnancy. Pregnant patients with an empty uterus on ultrasound but without clear signs of ectopic pregnancy, such as extra-uterine gestational sac, adnexal mass, or free fluid, are classified as having a “pregnancy of unknown location” and require reliable follow-up until the pregnancy location can be confirmed.7

(click for larger image) Table 1: IUD Types

* Immediately after an abortion, childbirth, or transitioning contraceptive methods.1

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

Risk of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is elevated in the first three weeks following IUD insertion, before returning to baseline rates.4,8 IUD insertion is contraindicated in women with current purulent cervicitis or known chlamydial/gonorrheal infection until treatment is complete and symptoms have resolved.1,8 If PID is diagnosed in an individual with an IUD in place, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines recommend leaving the IUD in place (outcomes are similar whether the IUD is removed or left in place).4 PID should be treated the same as in patients without IUDs in place and requires follow-up within 48 to 72 hours to assess for clinical improvement. If clinical improvement fails to occur, IUD removal should then be considered.5 There are currently no CDC recommendations on management of tubo-ovarian abscess in a woman with an IUD. Current protocols call for inpatient treatment with IV antibiotics, with consideration of IUD removal if clinical improvement is not observed.5

Expulsion

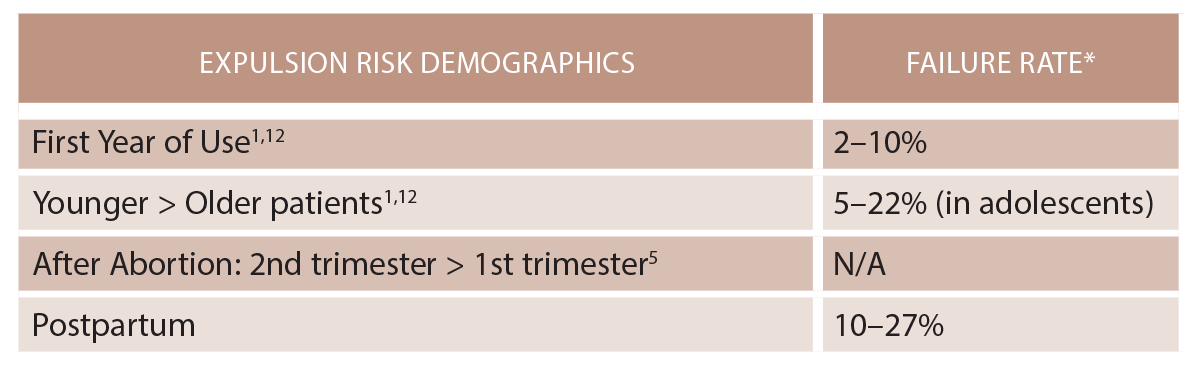

If expulsion is suspected, pelvic exam should be performed to assess for the IUD strings or a partially expelled IUD protruding out of the cervical os.5 If the IUD and strings are not present, imaging such as an ultrasound, abdominal radiograph, or CT should be obtained for IUD localization and potential perforation. If the IUD cannot be located, it may have been fully expelled. See Table 2 for information on expulsion risk.

(click for larger image) Table 2: IUD Expulsion

* Failure rate range is 0.1 to 2.2 per 100 women years.11

Perforation

Uterine perforation is a potentially serious complication of IUD use and can lead to invasion and migration to abdominal and pelvic organs. The IUD may be embedded in the myometrium or translocate through the uterus to the abdominal cavity. Migration to adjacent organs can lead to bowel obstruction, peritonitis, fistula formation, obstructive uropathy, and intraperitoneal adhesions.3

Primary perforation occurs during insertion and is typically associated with severe abdominal pain.3 Secondary perforation is a delayed event and can present as chronic abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding, missing strings, or even asymptomatically.3 The incidence of uterine perforation is estimated at between 0.2 and 3.6 per 1,000 insertions.2

Imaging for IUD localization should be performed with ultrasound, abdominal X-ray, and/or CT scan. Eighty percent of IUDs are found in the peritoneal cavity after perforation.3 There is no substantial difference in prevalence of perforation between levonorgestrel and copper IUDs; adhesions are more highly associated with copper IUDs.2,9 Risk factors for uterine perforation include breastfeeding, postpartum state, lack of experience by the health care provider performing insertion, extreme anteflexion or retroflexion of the uterus or uterine abnormalities, multiparity, nulliparity, history of cesarean delivery, and myomectomy.9 Patients may require hysteroscopy, cystoscopy, colonoscopy, laparoscopy, or exploratory laparotomy depending on IUD location.

Immediate Complications of the IUD Insertion Procedure

Some patients may develop pain with IUD insertion. Nulliparity and history of severe dysmenorrhea are associated with greater insertion-related pain.4 Some pain, such as cramping and changes in bleeding pattern, may be normal in the initial weeks after IUD placement. Some patients may develop vasovagal reactions with syncope, nausea, and/or vomiting. Because primary uterine perforation can occur during insertion and cause severe pain, these patients may need to be evaluated with pelvic examination and further imaging to assess IUD location and determine if primary perforation has occurred. IUDs can lead to irregular menstrual bleeding, which typically improves with time.5 For these patients, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications are first-line therapies for treating dysmenorrhea and abnormal bleeding.4 Naproxen in particular has been shown to decrease pain and bleeding.1

IUD Removal in the ED

IUDs rarely require removal in the emergency department. Some circumstances do require this, including a partially expelled IUD causing pain and bleeding. The procedure for IUD removal is simple: Grasp the strings securely using ring forceps and apply gentle traction outward. If IUD removal with gentle traction and without resistance is unsuccessful, the procedure should be discontinued as the IUD may be embedded, perforated, or translocated. Such instances likely require hysteroscopy or laparoscopy for further evaluation.

Case Resolution

A point-of-care urine pregnancy test is positive. Pelvic examination shows a closed cervical os with IUD strings visible, no vaginal bleeding, and left adnexal tenderness. Point-of-care ultrasound shows an empty uterus, no free fluid, and possible left adnexal mass. The patient is taken to the operating room by ob-gyn for diagnostic laparoscopy, leading to the diagnosis of a left adnexal unruptured ectopic pregnancy. Salpingectomy is performed. The patient is discharged from the hospital and later decides to have her IUD removed as an outpatient because of anxiety related to possibility of developing a future ectopic pregnancy.

Dr. Goett is an assistant professor and assistant director for advanced chronic illness and bioethics in the departments of senior residents emergency medicine and palliative care at New Jersey Medical School and Rutgers University in Newark.

Dr. Shaker is a senior resident in emergency medicine at New Jersey Medical School and Rutgers University.

References

- Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology, Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Work Group. Practice bulletin No. 186: long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e251-e269.

- Kho KA, Chamsy DJ. Perforated intraperitoneal intrauterine contraceptive devices: diagnosis, management, and clinical outcomes. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(4):596-601.

- Cheung M, Rezai S, Jackman JM, et al. Retained intrauterine device (IUD): triple case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2018;2018:9362962.

- Hillard PJA. Practical tips for intrauterine device counselling, insertion, and pain relief in adolescents: an update [published online ahead of print Feb. 22, 2019]. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Gynecologic Practice; Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptive Expert Work Group. Committee opinion No. 672: clinical challenges of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(3):e69-77.

- Brahmi D, Steenland MW, Renner RM, et al. Pregnancy outcomes with an IUD in situ: a systematic review. Contraception. 2012;85(2):131-139.

- Neth MR, Thompson MA, Gibson CB, et al. Ruptured ectopic pregnancy in the presence of an intrauterine device. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2018;3(1):51-54.

- Jatlaoui TC, Simmons KB, Curtis KM. The safety of intrauterine contraception initiation among women with current asymptomatic cervical infections or at increased risk of sexually transmitted infections. Contraception. 2016;94(6):701-712.

- Heinemann K, Reed S, Moehner S, et al. Risk of uterine perforation with levonorgestrel-releasing and copper intrauterine devices in the European Active Surveillance Study on Intrauterine Devices. Contraception. 2015;91(4):274-279.

- Godfrey EM, Folger SG, Jeng G, et al. Treatment of bleeding irregularities in women with copper-containing IUDs: a systematic review. Contraception. 2013;87(5):549-566.

- Heinemann K, Reed S, Moehner S, et al. Comparative contraceptive effectiveness of levonorgestrel-releasing and copper intrauterine devices: the European Active Surveillance Study for Intrauterine Devices. Contraception. 2015;91(4):280-283.

- Jatlaoui TC, Riley HEM, Curtis KM. The safety of intrauterine devices among young women: a systematic review. Contraception. 2017;95(1):17-39.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 | Multi-Page

No Responses to “How to Approach Patients Who Have an Intrauterine Device”