Pediatric elbow injuries are among the most challenging musculoskeletal conditions for emergency physicians. Kids can be a challenge to examine, large cartilaginous areas and various elbow ossification centers make X-rays difficult to interpret, and many missed injuries are both subtle and require operative management.1

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 39 – No 08 – August 2020Those of us who manage kids with acute elbow injuries undoubtedly see pulled elbows and supracondylar fractures. We look for effusions on lateral X-rays, think about the anterior humeral line, and possibly recall the mnemonic CRITOE (see below). Supracondylar fractures comprise 60 to 70 percent of pediatric elbow fractures; the bulk of the rest are two commonly missed fractures. Recognizing the other 30 to 40 percent requires awareness of those diagnoses and their clinical presentations.2,3 Knowing the clinical relevance of CRITOE helps identify this pair of less common, subtle pediatric elbow injuries that are often operative.

Two Commonly Missed Pediatric Elbow Fractures

Two diagnoses make up the bulk of nonsupracondylar pediatric elbow fractures: lateral condyle (LC) fractures (~15 percent) and medial epicondyle (ME) fractures (~10 percent). This implies that we should diagnose one LC or ME fracture for every two to three supracondylar fractures. If not we may be missing them.

LC fractures are fractures of the metaphysis of the lateral aspect of the distal humerus. These fractures are typically seen in 4- to 10-year-olds and are often misdiagnosed as supracondylar fractures.

ME fractures are avulsions of the ossification center that sits on the medial condyle. These are typically seen in older kids (ages 10 to 16) and are often missed.

(Note the nomenclature: medially, an avulsion of the ossification center that sits on top of the condyle (epi is Greek for “on top of”)—medial epicondyle fracture; laterally, a fracture involving the metaphysis of the distal lateral humerus—lateral condyle fracture.)

By knowing CRITOE and the approximate ages of appearance, a fracture fragment in a younger child will not be mistaken for an ossification center.

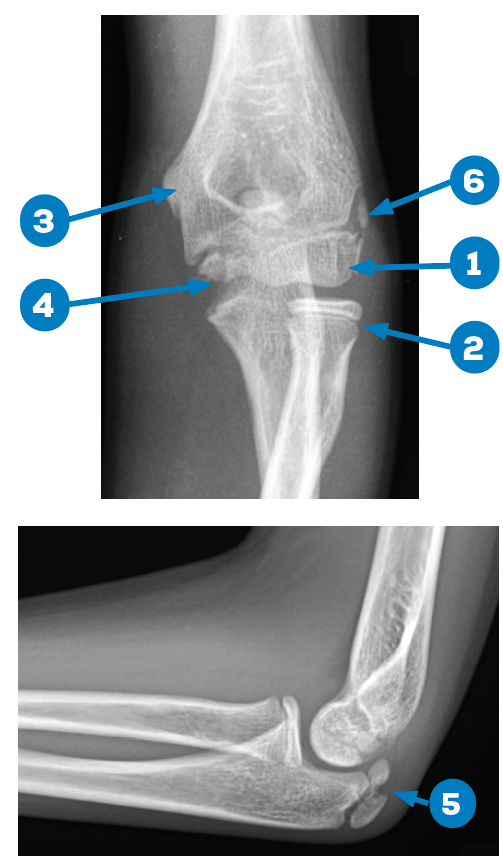

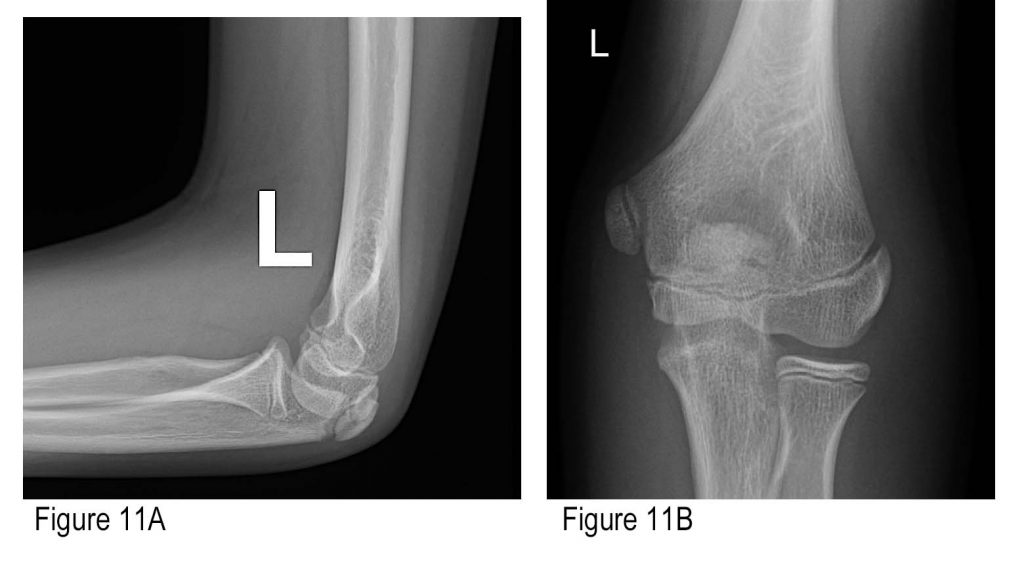

Figures 1A and 1B: Normal X-rays, 13-year-old male. 1) capitellum; 2) radial head; 3) internal (medial) epicondyle; 4) trochlea; 5) olecranon; and 6) external (lateral) epicondyle. Credit: Arun Sayal

Let’s run through it. The elbow has six ossification centers. CRITOE reminds us of their names and the specific order in which they ossify. Their clinical relevance rests on knowing the order and approximate ages in which they ossify, and therefore appear on X-ray (See Figures 1A and 1B).

In order of appearance, the six are:

C: Capitellum (lateral aspect of distal humerus)

R: Radial head (distal neighbor of capitellum)

I: Internal (or medial) epicondyle

T: Trochlea (distal neighbor of I, at medial aspect of distal humerus)

O: Olecranon (best seen on the lateral view)

E: External (or lateral) epicondyle

Because ossification always appears in this exact sequence, the presence of any single ossification center mandates the radiographic identification of those that precede it.

CRITOE can also approximate the age at which the six ossification centers often appear, albeit these are rough estimates due to significant child-to-child variability. Timing varies by sex. For girls, use odd years starting at 1; for boys, use even years starting at 2 (see Table 1).

Table 1: Approximate Age (±18 Months) at Which Six Elbow Ossification Centers

Appear on X-ray for Girls and Boys

| Ossification Centers | C | R | I | T | O | E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls’ Ages | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 11 |

| Boys’ Ages | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 |

For example, for a girl, the radial head (R) ossification center should appear at 3 years but can range from 1.5 to 4.5 years (3 years ±18 months). For a boy, the trochlea (T) should appear at 8 years but can range from 6.5 to 9.5 years (8 years ±18 months).

These are rough estimates due to significant child-to-child variability. Since it can be these ages ±18 months, CRITOE crudely predicts the age of appearance.

A far more accurate indicator of normal however, is comparing the injured to the uninjured elbow. Each elbow should be a very close copy (within 3 to 4 months) of its pair. Comparative films can help confirm suspicious X-ray findings (ossification centers, lucencies, alignment, and so forth). This option should be used selectively after reviewing X-rays of the injured elbow and not as a matter of routine.

Here are four cases in which correctly applying the CRITOE mnemonic can lead to better outcomes. All of the fractures described here are closed, isolated pediatric elbow injuries that are neurovascularly intact with normal compartments. Reviewing the four cases will highlight the clinical relevance of CRITOE in diagnosing LC and ME fractures.

Case 1: 7-year-old boy fell off monkey bars.

Case 2: 6-year-old girl fell on a trampoline.

Case 3: 13-year-old boy threw a dodgeball, didn’t fall, but felt immediate pain at the inside of his elbow.

Case 4: 10-year-old girl injured her elbow doing a cartwheel.

CRITOE and Lateral Condyle Fractures

Case 1: 7-year-old boy fell off monkey bars.

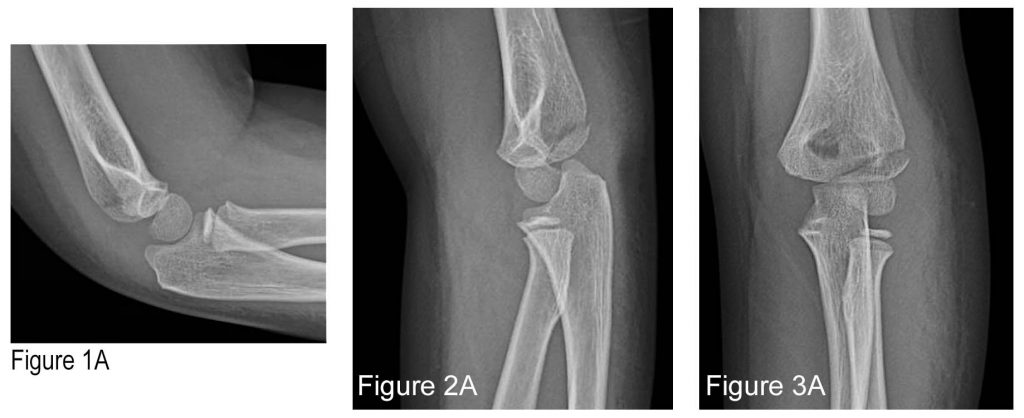

Figure 1B: Lateral view with markings. The small, subtle, anterior “sail sign” suggests an effusion (short arrow) and a subtle lucency at the posterior aspect of the distal humerus (long arrow). Credit: Arun Sayal

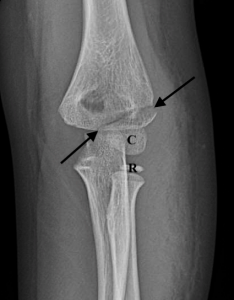

Figure 2B: Oblique view with marking. This shows a lucency that exits posteriorly with a minimal step-off (arrow). Credit: Arun Sayal

Figure 3B: AP view with markings. An oblique lucency above the capitellum and a minimal step-off laterally (arrows). C: capitellum. R: radial head. Credit: Arun Sayal

Some may interpret the lucency above the capitellum as the edge of an ossification center. CRITOE dispels that.

It is important to remember the radius is always lateral on elbow X-rays. The capitellum and radial head are seen in Figure 3B. If the identified lucency was a physis, it would be of the external (or lateral) epicondyle (E). But CRITOE as an age predictor tells us that the lateral epicondyle (E) appears last (in boys, at ~12 years of age ±18 months). It cannot appear at 7 years of age. So, the lucency cannot be part of an ossification center, and in this context, it represents a fracture. Further, if it was E (external), CRITOE mandates the presence of all the preceding ossification centers. We see C and R, but we cannot see I, T, or O. Therefore, that lucency cannot be E (a normal ossification center), and it represents a fracture. As lateral condyle fractures go, this case is a fairly obvious example—and yet, even it may be challenging to recognize.

Case 2: 6-year-old girl fell on a trampoline.

Figure 4B: Lateral view with marking. This shows a slightly rotated view; no definite effusion seen, but there is a lucency seen at the posterior aspect of the distal humerus with a small step-off (arrow). Credit: Arun Sayal

Figure 5B: AP view with markings. This shows two very subtle lucencies (arrows) seen superior and superolateral to the capitellum, consistent with a lateral condyle fracture. Credit: Arun Sayal

Figure 5C: Outline of the Salter-Harris IV pediatric lateral condyle fracture pattern, involving the metaphysis with extension through the nonossified part of the capitellum—though the extension into the elbow joint is not visible on X-ray. Credit: Arun Sayal

Just as in case Case 1, these X-rays cannot be part an ossification center (a 6-year-old girl is too young for the E, and there is no X-ray evidence of ossification centers I, T, or O). As LC fractures go, this case is a more subtle example—and even harder to recognize than Case 1.

As shown in Figure 5C, LC fractures can represent either a Salter-Harris II fracture (through the physis and metaphysis) or a Salter-Harris IV fracture (through the metaphysis, physis, and epiphysis). If a Salter-Harris IV variant, the intra-articular component is often through the nonossified part of the capitellum and presumed, but not visible, on X-ray.

LC fractures may be intra-articular. Minimally displaced (<2 mm) may be either treated nonoperatively or operatively. If there is 2 mm or more displacement, these are typically treated operatively.3 Complications include non-union, mal-union, growth disturbance, and ulnar nerve palsy.3,4 Orthopedic consultation in the emergency department is recommended for LC fractures.

The child in Case 2 was diagnosed in the emergency department; a well-padded posterior slab was applied, and orthopedics was contacted. Arrangements were made for follow-up two days later for K-wire fixation (see Figure 10).

CRITOE and Medial Epicondyle Fractures

Approximately 10 percent of pediatric elbow fractures involve the ME. CRITOE helps us identify this commonly missed fracture.

The ME is the origin of the ulnar collateral ligament and forearm flexors. A valgus strain (a medially directed force) to a child with open growth plates can avulse the ME. This injury typically happens in 10- to 14-year-old girls or 12- to 16-year-old boys. The fragment’s position varies from nondisplaced to completely separated from the joint.

A pediatric elbow dislocation is relatively uncommon, but if seen, it is commonly associated with an avulsed ME.

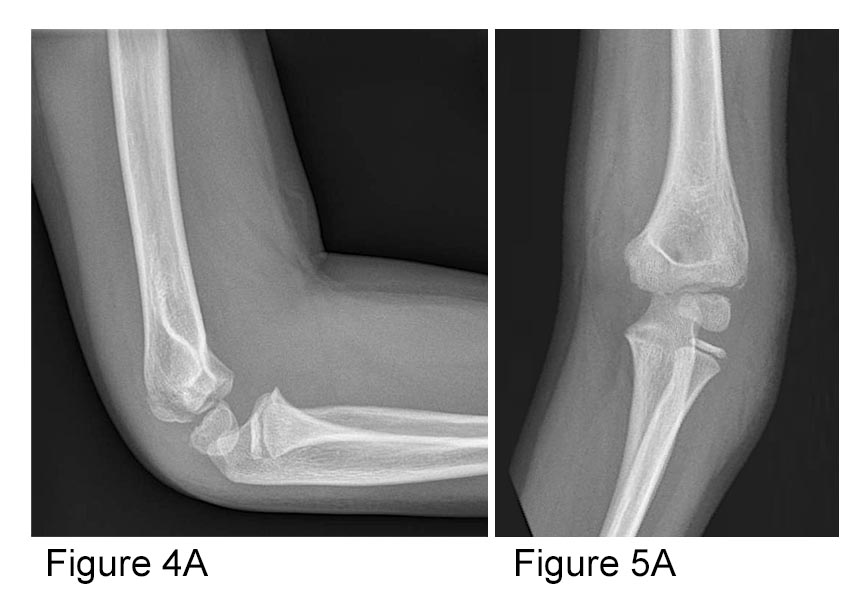

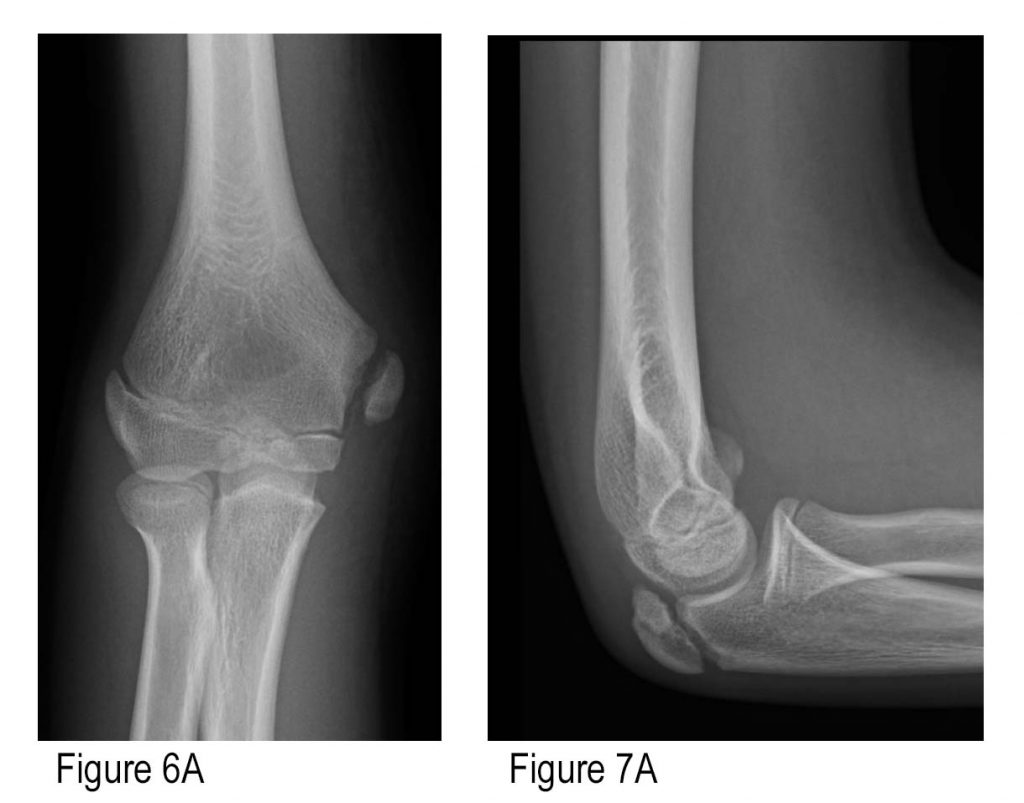

Case 3: A 13-year-old boy threw a dodgeball and felt pain at the inside of his right elbow. He is tender over the medial epicondyle.

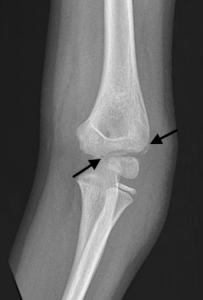

Figure 6B: AP view with markings. This identifies the ossification centers of the capitellum (C), radial head (R), internal (medial) epicondyle (I), and trochlea (T). Two black lines show a medial condyle physis slightly wider than the other growth plates on the image. Credit: Arun Sayal

Figure 7B: Lateral view with markings. This shows the ossification center of the olecranon (O). Also note the probable anterior displacement, presumably of the medial epicondyle (arrow). Credit: Arun Sayal

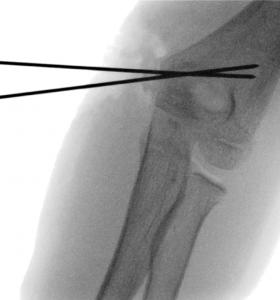

With a 13-year-old boy, it is reasonable to see C, R, I, T, and O, but not yet E. (E is the last ossification center, and in boys, it should appear at 12 years ±18 months). Scrutinizing the ME, the physis is wider than other growth plates. The lateral view is suspicious for very subtle anterior displaced fragment, likely the ME. These findings correlate with the patient’s story and exam.

To confirm, an X-ray of the patient’s opposite, uninjured elbow was obtained (see Figure 11). This verified the abnormalities suspected on the X-rays of the injured elbow. This child was managed in a posterior slab, seen in clinic a week later, and healed well after four weeks of immobilization and some time.

Figures 11A and B: AP and lateral of comparison (left) elbow. A shows a narrower medial condyle physis; B shows no anterior displacement of a distal humeral fragment. Credit: Arun Sayal

Case 4: 10-year-old girl injured her elbow doing a cartwheel.

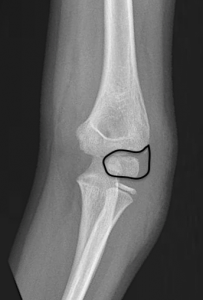

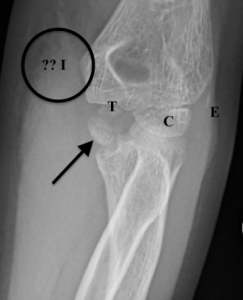

Figure 8B: AP view with markings. Ossification centers of capitellum (C), trochlea (T), and a sliver of external (lateral) epicondyle (E) are seen. The internal (medial) epicondyle (“?? I” in circle) is missing from its expected location and is identified by the arrow, avulsed into the joint. There is also significant medial soft tissue swelling near the circle. Credit: Arun Sayal

Figure 9B: Lateral view with markings. Ossification centers of capitellum (C), radial head (R), and olecranon (O), are seen. The internal (medial) epicondyle is identified by the arrow, avulsed into the joint. There is also a slightly rotated small anterior fat pad seen (A) (not a “sail sign” morphology, however, so this is normal) and very small posterior fat pad (P) (always abnormal). Credit: Arun Sayal

In this case, apply CRITOE (for order): Ossification centers of capitellum (C) and radial head (R) are seen. Internal (medial) epicondyle (“?? I” in circle) is missing from its expected location. Since trochlea (T), olecranon (O), and a sliver of external (lateral) epicondyle (E) are also seen, the internal (medial) epicondyle must be visible. It is identified by the arrow on Figures 8B and 9B, avulsed into the joint. Of note, on Figure 9B, again slightly rotated, are a small anterior fat pad (A) (not a “sail sign” morphology, so this is normal) and a very small posterior fat pad (P) (always abnormal). Also present on the AP view is significant medial soft tissue swelling (in the vicinity of the circle in Figure 8B).

For any of the six ossification centers seen, CRITOE mandates we account for every ossification center that precedes it. As such, when we see T, O, or E, we must account for every letter before it in the mnemonic—including the I. This case highlights the most commonly avulsed (and therefore “missing”) ossification center—the medial epicondyle. When not located in its normal position, closer inspection reveals an ossific density in the joint that has to be the medial epicondyle. Again, this is easy to miss. Understanding CRITOE helps us identify it.

This avulsion was identified in the emergency department and discussed with orthopedics. A posterior slab was applied, and the patient was discharged with follow-up arranged. Two days later, reduction and K-wire fixation occurred (see Figure 12).

ME fractures with less than 5 mm displacement typically require nonoperative management with a posterior slab and close follow-up. Any displacement warrants an emergency department consultation with orthopedics.

- If there is 5 to 15 mm of displacement, operative management becomes more likely

- If there is >15 mm displaced, operative management is highly likely.5

Again, recall that LC fractures are quite different; minimally displaced (<2 mm) may be either treated nonoperatively or operatively. When there is 2 mm or more displacement, operative management is typical.3

Summary

Kids’ fractures heal faster than adults’ fractures do. That means that for LC and ME fractures, if either diagnosis is missed, or the need for operation goes unrecognized, then a week of waiting before being evaluated by a surgeon might impair their ability to perform a closed reduction when indicated. That potentially leaves open reduction as the only option, which is inherently more complicated than closed.

Pediatric lateral condyle fractures and medial epicondyle fractures are uncommon; they are commonly missed, commonly subtle, and commonly operative. ME fractures that are definitively <5 mm displaced can be placed in a posterior slab and be followed by orthopedics within a week. For all other ME and LC diagnoses (confirmed or suspected), it is safer to discuss the case directly with orthopedics to review the X-rays, confirm management plans, and then arrange close follow-up.

Kids’ elbow injuries are tricky. Be methodical and complete by understanding how CRITOE helps recognize underdiagnosed factures.

Dr. Sayal is a staff physician in the emergency department and fracture clinic at North York General Hospital in Toronto, Ontario; creator and director of CASTED ‘Hands-On’ Orthopedic Courses; and associate professor in the department of family and community medicine at the University of Toronto.

Dr. Sayal is a staff physician in the emergency department and fracture clinic at North York General Hospital in Toronto, Ontario; creator and director of CASTED ‘Hands-On’ Orthopedic Courses; and associate professor in the department of family and community medicine at the University of Toronto.

References

-

- Shrader MW, Campbell MD, Jacofsky DJ. Accuracy of emergency room physicians’ interpretation of elbow fractures in children. Orthopedics. 2008;31(12).

- Iyer RS, Thapa MM, Khanna PC, Chew FS. Pediatric bone imaging: imaging elbow trauma in children—a review of acute and chronic injuries. Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198:1053-1068.

- Lateral condyle fracture of the humerus – Emergency Department. The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne website. Available at: https://www.rch.org.au/clinicalguide/guideline_index/fractures/Lateral_condyle_fracture_of_the_humerus_Emergency_Department_setting/Accessed April 28, 2020.

- Boutis K. The emergency evaluation and management of pediatric extremity fractures. Emerg Med Clin N Am. 2020;38(1):31-59.

- Medial epicondyle fracture of the humerus – Emergency Department. The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne website. Available at: https://www.rch.org.au/clinicalguide/guideline_index/fractures/Medial_epicondyle_emerg/. Accessed April 28, 2020.

No Responses to “How to Avoid Missing a Pediatric Elbow Fracture”