Ultrasound-guided single injection nerve blocks have become a valuable tool in the multimodal strategy for pain control in the acutely injured emergency department patient. Specifically, the ultrasound-guided interscalene brachial plexus block (ISNB) has been shown to be ideal in the emergency department for pain control after upper-extremity fractures (distal clavicle and humerus) and as an alternative to procedural sedation for glenohumeral reductions. Other indications include large abscess drainage, burns, deep wound exploration, and complex laceration repair.1–4

Explore This Issue

ACEP Now: Vol 39 – No 04 – April 2020In more than 10 years of clinical experience performing and teaching this invaluable tool to numerous residents and faculty, we have learned a couple simple tips that can help improve block success. The first deals with a simplified/alternative method to locate the relevant sonoanatomy, and the second defines a fascial landmark that can be targeted for anesthetic deposition. Awareness of common pitfalls may reduce block difficulty and allow the single injection ultrasound-guided interscalene nerve block to become integrated into the multimodal pain management of the acutely injured emergency department patient.

For a more detailed explanation of this procedure that includes safety principles, patient positioning, and block basics, please refer to the previous article on ultrasound-guided femoral nerve blocks published in ACEP Now.

1) Simplify the hunt for the “stoplight” sign: Use the traceback technique.

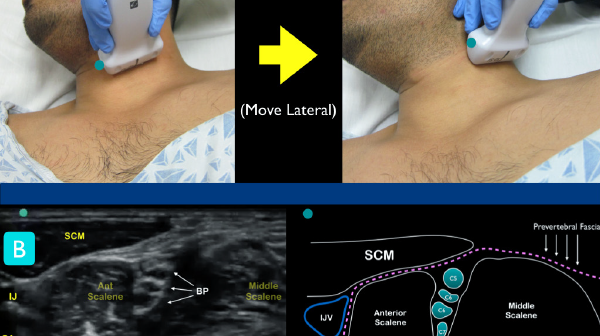

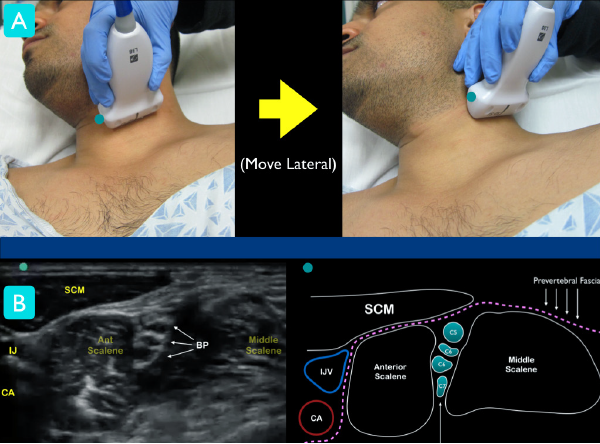

As the name implies, the interscalene brachial plexus can be found between the anterior and middle scalene muscles in the neck (commonly called the “stoplight” sign because of the vertically oriented anechoic C5-C7 nerve roots). To locate this landmark, the classic teaching has been to initially place a high-frequency linear transducer in a transverse orientation (probe marker facing to the right of the patient) at the level of the larynx, identifying the internal jugular vein (IJV) and carotid artery (CA). Then slowly slide the transducer laterally until the border of the clavicular head of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) comes into view (at the top of the ultrasound screen). At this level, the anterior and middle scalene muscles lie just below the SCM and act as important sonographic landmarks. Between the muscles lie the anechoic and round C5-C7 roots of the brachial plexus, the stoplight sign (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Figure 1A: Classic technique for locating the interscalene brachial plexus. At the level of the larynx, slide lateral until the ultrasound landmarks are noted

Figure 1B: Just under the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM), locate the anterior and middle scalene muscles. The interscalene groove will contain the nerve roots of the brachial plexus. Note the internal jugular vein (IJV) and carotid artery (CA) on the medial aspect of the anterior scalene muscle.

Unfortunately, this ultrasound landmark can be difficult to locate for the less-experienced sonographer. Variation of individual neck anatomy and lack of clear sonographic landmarks make locating the stoplight sign in the interscalene groove frustrating for many of our learners. For this reason, we commonly teach an alternative technique that relies on visualizing the subclavian artery in cross-section in the supraclavicular fossa. The traceback technique (as it has been called) starts by placing the transducer transversely in the supraclavicular fossa and aiming caudally until the subclavian artery is visualized. The brachial plexus lies just posterolateral to the artery at this level and will appear as a tight group, a hypoechoic “cluster of grapes.” Follow these hypoechoic structures cephalad until they form the stoplight sign within the interscalene groove at the level of the larynx (see Figure 2). We have found this alternative technique to be invaluable for our learners (and even experienced clinicians).5,6

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

One Response to “How to Perform Ultrasound-Guided Interscalene Nerve Blocks”

May 6, 2020

Vir SinghExcited to implement this in my practice and share this with my residency program